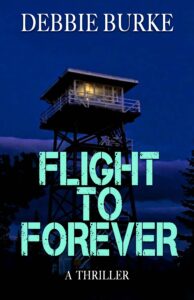

My new t-shirt!

by Debbie Burke

Last weekend, I drove to Helena, MT to participate in the Montana Writers Rodeo, an intimate gathering of about 40 people. The event is only in its second year, but it ran as well as if they’d been hosting conferences for years.

In 2017, director/playwright/actor Pamela Mencher went on a search for a venue where locals could perform plays that they’d written, along with artistic, musical, and cultural activities. She recognized potential in a vacant industrial building and set to work with volunteers to convert the space into the Helena Avenue Theatre (visit the Montana Playwrights Network website). It’s now a cozy auditorium with a stage, comfortable theatre seating, plus gathering rooms.

Often, attendees at writing conferences are shy introverts who may be uncomfortable in a crowd. Not at this Rodeo!

Perhaps one reason is some members of the group are also actors. On Friday evening, after a delicious buffet supper, eager authors went onstage to read their poetry, short stories, and novel excerpts. That icebreaker loosened everyone up and made for a friendly atmosphere.

On Saturday, acclaimed author Russell Rowland recalled his rollercoaster writing career, starting with his dream internship at Atlantic Monthly and the initial success of his first novels. Disappointment followed when his publisher left him an orphan. Ultimately, he made several comebacks and now has seven books, a podcast, and a popular radio show, Fifty-Six Counties. He related how discouragement and pain are emotional wellsprings from which the most meaningful writing emerges.

In his workshop prompt, he asked us to write about an argument remembered from our childhood. His unique slant: relate the argument from the point of view of the other person.

Russell’s warm, approachable demeanor encouraged a 12-year-old author to take the stage to read what he’d written. How cool is that! Surrounded by adult strangers, this young writer actively participated, asked questions, and discussed his aspirations.

Debbie with actor/director/writer Leah Joki

Another presenter was actor/director/writer Leah Joki, author of Julliard to Jail, a memoir about her unconventional career as a writing and theatre teacher inside prisons. “The reason I’m comfortable in prison,” she says, “is I grew up in Butte!” That caused laughs among us Montanans who understood exactly what she meant.

Her workshop enlisted audience volunteers who read parts of Huckleberry Finn and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf to demonstrate the impact of dialogue in fiction. She said, “Every word matters.” Yet she also emphasized that silence—what is not said—can be even more dramatic.

The workshop I taught was on DIY editing with 10+ tips on how to edit your own writing. In my next post, I’ll outline those tips.

As part of my presentation, I offered to critique First Pages from participants (wonder where that idea came from!). They were submitted in advance, so I had time to review and edit, using track changes.

During the workshop, I projected a page on the screen, read it aloud, then gave my impressions and explained reasons for suggestions. Time didn’t permit review of all submissions, but I printed out the edited versions for each author and we discussed them outside the workshop.

As often happens with TKZ First Pages, some stories didn’t get started until page two or later. We discussed ways to grab readers’ attention immediately, while at the same time weaving in enough details to ground them in the fictional world.

I plugged TKZ as a helpful resource and encouraged Rodeo attendees to submit their first pages for critique.

Rounding out the presentations were two representatives from Farcountry Press, a respected regional house that publishes outdoor guides, books on travel, history, photography, and nature-themed picture books. Samantha Strom, Director of Publications, and Hilary Page, marketing and social media, showed us how to define a reading audience. They provided blank template worksheets that we filled out with background, gender, age, education, interests, jobs, lifestyles, and values of our particular demographic.

Rodeo Wrangers Pamela Mencher, Mindy Peltier, Pearl Allen, and Christa Chiriaco

Conference wranglers Pamela Mencher, Mindy Peltier, Pearl Allen, and Christa Chiriaco rounded up strays and kept the Rodeo running smoothly.

For example, each presenter had a dress rehearsal with tech helpers who checked mic volume, lighting, position on stage, power point displays, and especially those pesky connecting cables! Thank goodness, because my Mac didn’t want to play nice with their projection setup. Mindy brought in the calvary (her techie husband) and saved the day.

Volunteer Intern Chinook asked an unexpected question: did I prefer chilled or room-temperature water during my presentation? According to audiobook narrators, room-temperature is better because cold causes throat muscles to tense up. How thoughtful of Chinook!

Coffee and snacks were in a room where we authors displayed our books for sale and chatted with attendees between sessions.

Small conferences offer a chance to relax and connect with other writers on a deeper level than the hectic hustle-bustle of large ones. Authors in similar genres swapped business cards with prospective critique partners and beta readers.

Several people asked about my editing services, leading to possible new clients. Plus, I sold a stack of books and traded with other authors.

Evaluation surveys are important planning tools for future conferences, but convincing attendees to fill them out is always a challenge. The Rodeo wranglers solved that problem by holding prize drawings as the last event on Saturday evening. A completed survey earned a ticket to win t-shirts, drink containers, and other Rodeo-themed gifts. Yup, I won that t-shirt shown at the top of this post.

Deep Fake Sapphire Pen created by Steve Hooley

I piggy-backed on their drawing with my own to encourage signups for my newsletter. The prize: a custom-crafted Steve Hooley legacy wood pen. The lady who won the Deep Fake Sapphire pen was thrilled and I went home with a bunch of new subscribers. Win-win.

For two nights, Mindy spoiled me with five-star hospitality in her lovely log home, complete with an espresso machine in my room.

The drive between Kalispell and Helena is 400 miles roundtrip, with a posted speed limit of 70 mph in most places. I’ll be polite and call that optimistic, rather than insane. Switchbacks and hairpin turns often reduce speed to a white-knuckled 20 or 30 mph.

The route follows winding rivers and twisting two-lane mountain roads that cross the Continental Divide. The drive takes four hours each way, cuz I’m too chicken to put cruise control on 70. I took time to admire Big Sky scenery while watching for suicidal deer and elk. Even plotted a few new scenes, too.

Near Flesher Pass on the Continental Divide, elevation 6131 feet

Already I’m looking forward to next year’s Montana Writers Rodeo.

~~~

TKZers: Do you prefer large or small writing conferences? Please share your favorite conference experience.

~~~

At the Rodeo, Flight to Forever and Deep Fake Double Down were the biggest sellers. Please click on the covers for sales links.

“La Barbe Bleue” (Bluebeard) is a French folk tale, first published in 1697. It tells the story of a rich man with an odd, bluish beard who marries women, slits their throats, and hangs their bodies on hooks in the basement of his castle.

“La Barbe Bleue” (Bluebeard) is a French folk tale, first published in 1697. It tells the story of a rich man with an odd, bluish beard who marries women, slits their throats, and hangs their bodies on hooks in the basement of his castle.

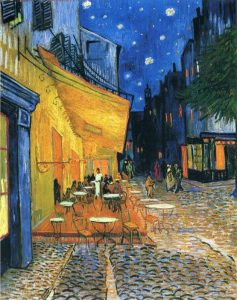

This isn’t to say that Van Gogh was murdered as in an intentional homicide case. As a former police investigator and coroner, I’m well familiar with death classifications. The civilized world has long used a universal death classification system with five categories. They are natural death, accidental death, death caused by wrongful actions by another human being which is a homicide ruling, self-caused death or suicide, and an undetermined death classification when the facts cannot be slotted into one conclusive spot.

This isn’t to say that Van Gogh was murdered as in an intentional homicide case. As a former police investigator and coroner, I’m well familiar with death classifications. The civilized world has long used a universal death classification system with five categories. They are natural death, accidental death, death caused by wrongful actions by another human being which is a homicide ruling, self-caused death or suicide, and an undetermined death classification when the facts cannot be slotted into one conclusive spot.

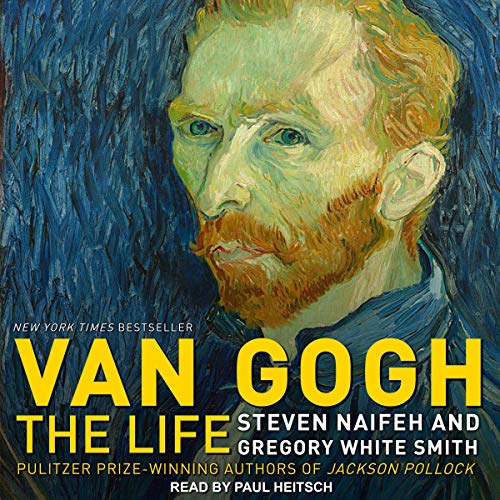

The researchers, Pulitzer Prize winners Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith who co-wrote

The researchers, Pulitzer Prize winners Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith who co-wrote