Op-art - to touch art with your eye

“I don't consider myself the 'father of op-art' and I hated the title of my first solo exhibition in New York. I was shocked by the term 'optical painting,' which diminishes the gravity of artistic searches, hard work, and creative assumptions – regardless of the visual form it may bring to mind. Martha Jackson used this term as a media provocation – how effectively! (…) Optical art has existed for millennia and is an expression of the visual search for human perception. Over the years, I've learned to accept this terminology and I adapted my own philosophy to it. Now op-art is just a name."

- Julian Stańczak

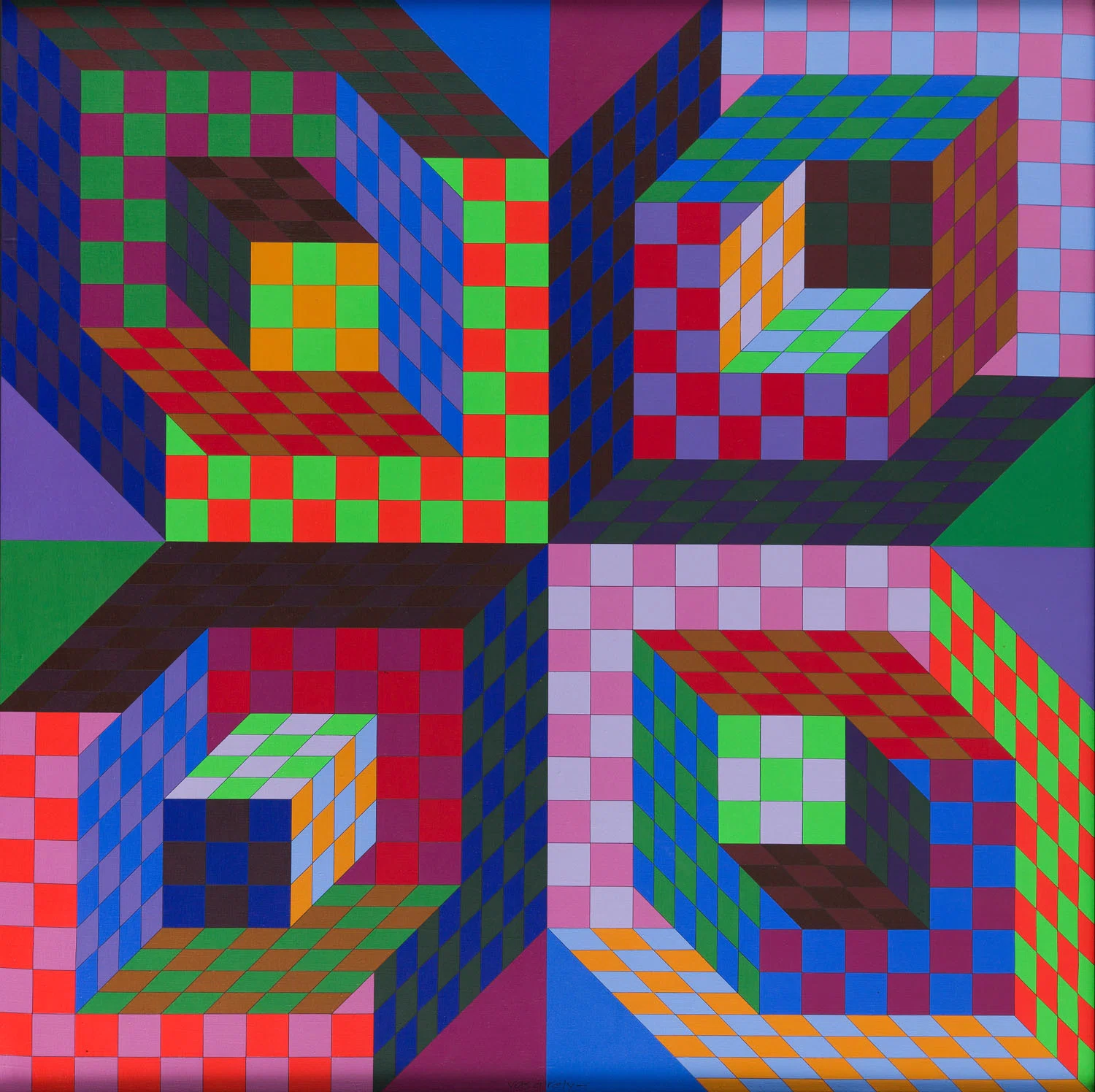

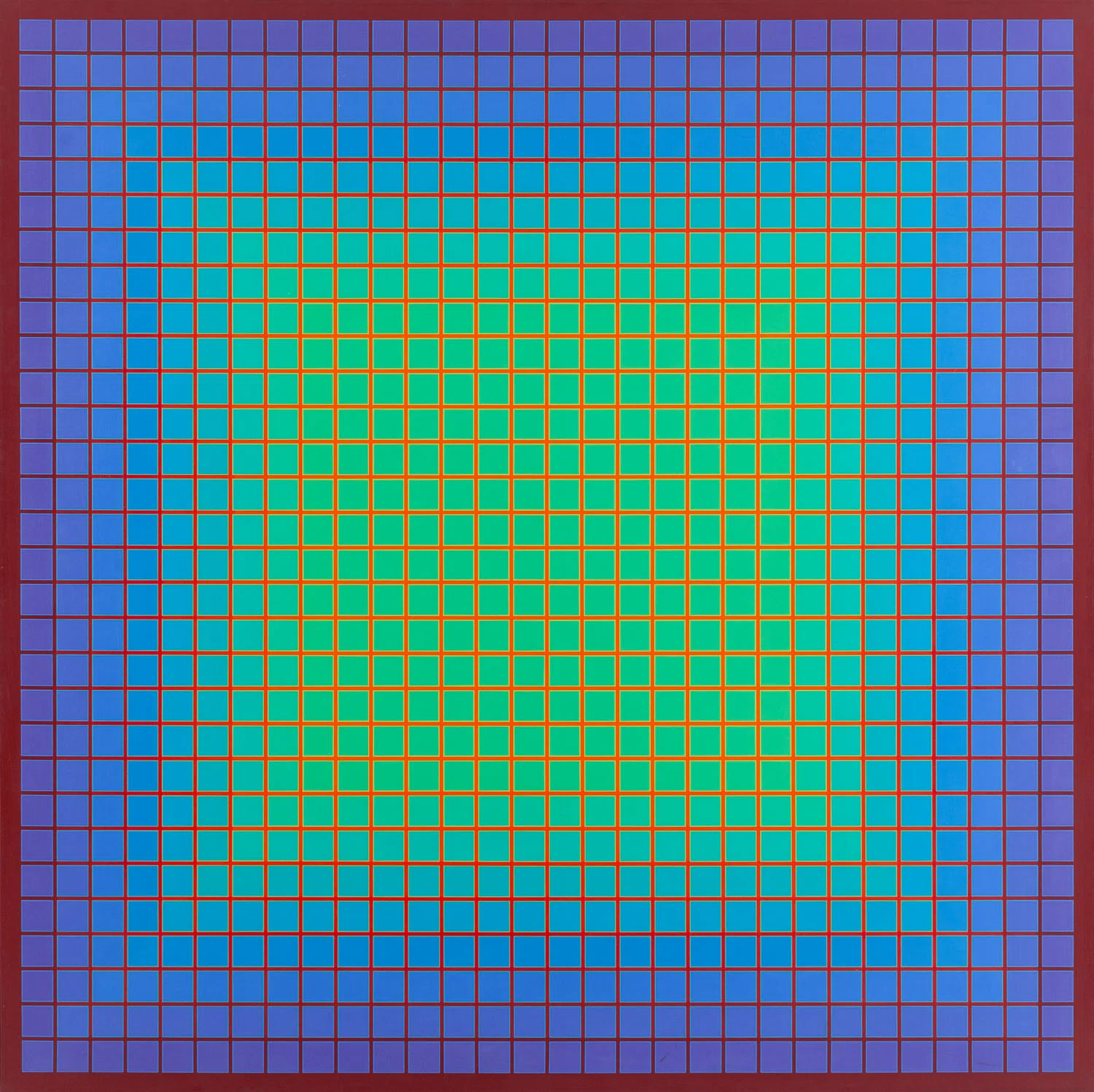

Recreating, Multiplication, and Expansion – in these three concepts Victor Vasarely saw a potential for new visual artistry, ready to emotionally move recipients. The main research problem for the artist was how to record movement by the sense of sight focused on a motionless work of art or the depth of space on the plane of a form. Soon, Vasarely was recognized as the father of optical art, and its creators gained appreciation around the world.

The work of optical art representatives was first appreciated and noticed thanks to Jon Borgzinner's 1964 article, "Op Art: Pictures that Attack the Eye," published in Time Magazine. The presented works by Victor Vasarely, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Julian Stańczak, and Ed Mieczkowski were particularly appreciated. Optical art was described as a new phenomenon in art based on research on the visual apparatus. The article also announced the inauguration of "The Responsive Eye" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by William Seitz. The exhibition consisted of 120 paintings and constructions made by 99 artists from 15 different countries. This display brought wide recognition to the representatives of op-art, thus constituting the movement as the leading trend in modern art. The exhibition strengthened the position of, among others, Josef Albers, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Henryk Berlew, Wojciech Fangor, Tadasky, Ed Mieczkowski, Vasarely, and Bridget Riley on the international art market. These artists, provoking a global discussion about the emerging art, proved that visual processing is not only mechanical – the appropriate perception requires the entire nervous system, affecting personal experiences and offering alternative ways of seeing, which had not been known and explored until then. In the curatorial text for the exhibition, Seitz pointed out that, together with op-art, the ideological concept of an artwork moved from the outside world, rushed through the artistic object, and entered the not quite researched area between the cornea and the brain of the recipient.

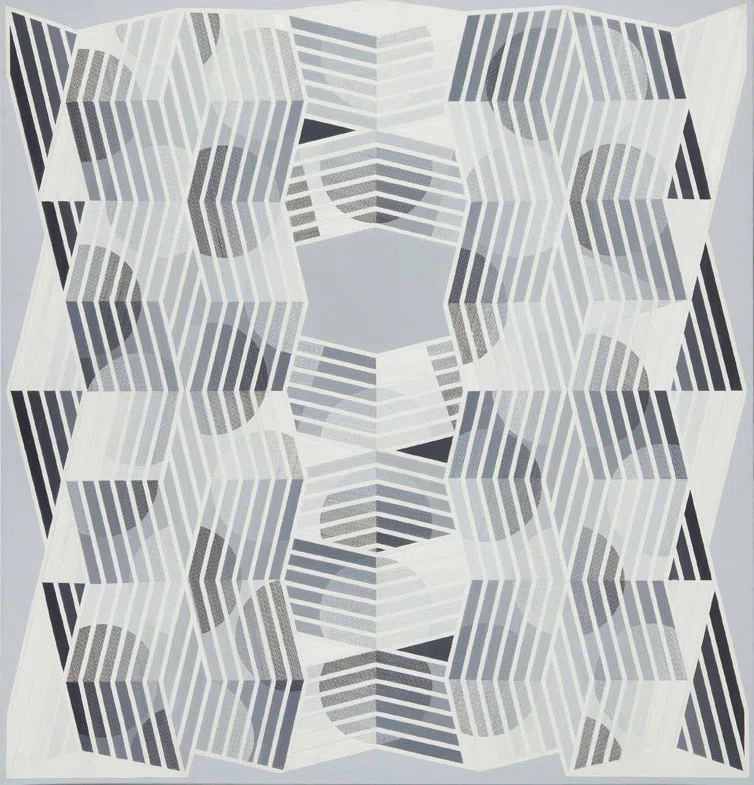

Cleveland, Ohio, was the key location for the development of American op-art. The Cleveland Institute of Art represented many renowned artists, whose works could be seen, among others, at Seitz's "The Responsive Eye" exhibition. The famous Anonima Group was also born there. The collective, co-created by Ed Mieczkowski, Ernst Benkert, and Francis Hewitt, was the only one in the United States that entirely devoted its work to optical art. Its representatives were against extreme consumerism as well as artists and their art conforming to the demands of the viewer. The purpose of their activities (both in painting and writing) was a precise investigation of scientific phenomena and the psychology of optical perception. The milieu around the Cleveland Institute of Art flourished in the 1960s and, at the same time, became a location where Polish representatives of op-art could find a common place for artistic practices. Marta Smolińska wrote about their activity at the university as follows:

"The student years at the Cleveland Institute of Art also brought Stańczak closer to two other artists with Polish roots, creating in the spirit of op-art: Richard Anuszkiewicz and Ed Mieczkowski. At university, Anuszkiewicz was one year senior to Stańczak, but they were united by friendship and discussions about art. Anuszkiewicz, who came from Erie, Pennsylvania, was somewhat 'adopted' by the Stańczak family, which settled in Cleveland, as was visible in their meals together and their group of mutual friends. After studying at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Ed Mieczkowski obtained a master's degree at the Pittsburgh Carnegie Mellon Institute. Later, in the years 1964-1995, they were both lecturers at their alma mater, Stańczak taught painting, and Mieczkowski mainly drawing. Spending the years of didactic work together gave them the opportunity to conduct constant debates about art and the status of painting, which often were turbulent due to differences in their views on art"

Marta Smolińska, Julian Stańczak. Op art i dynamika percepcji, Warsaw – Krakow 2014, p. 29.

American op-art remained inseparable with the person of Martha Jackson – a gallery owner who was in constant contact with the most important representatives of optical art and focused on the promotion of their works. Martha Jackson opened her gallery in Manhattan, New York in 1953. This place became frequented by artists and enthusiasts of contemporary art. Over 16 years, Jackson contributed to the promotion of names such as Julian Stańczak, Antoni Tapies, Barbara Hepworth, Marino Matini, and Sam Francis. The first "junk art" exhibition took place in 1960, and the first optical art exhibition followed five years later. In the mid-1960s, she founded the "Red Parrot Company" responsible for the production of films about artists and their works. She was also one of the first to introduce artistic prints made, among others, by Julian Stańczak, Sam Francis, and Karel Appel.

The innovative ideas of op-art representatives expanded artistic freedom and paved the way for further solutions in abstract art – thoughts and artistic action, which inspire artists to this day. The combination of research and scientific experiments in the artistic sphere allowed for the distance between creation and presentation to be overcome. Although the artistic experiments of optical art representatives may seem antagonistic to the idea of classical art history, they have nevertheless made art even more "tangible" and possible to be experienced than ever.