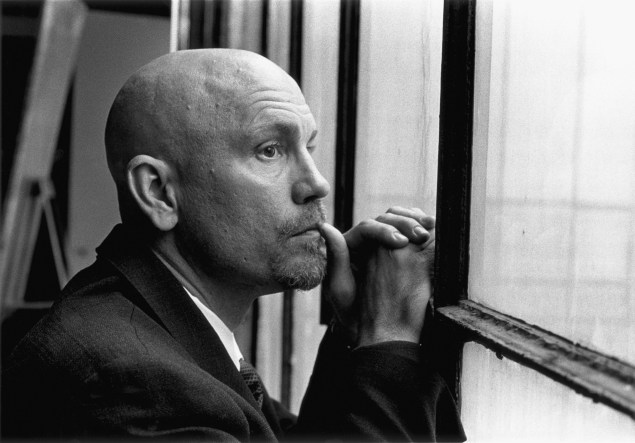

(Christian Coigny) Photo: Christian Coigny

There is a scene in the film Cesar Chavez where a vineyard owner learns that labor organizer Cesar Chavez plans to target the family business for a boycott. “What should we do?” the owner’s son asks. The owner is feeding his grandson and doesn’t answer right away.

“Zucchini?” he says, tenderly, handing the baby a piece of vegetable. Then he sighs. He doesn’t know the answer. He’s not the one who went to college. He’s merely the one who invested a lot of money in his only son, he says, hoping that one day the son would be able to answer one simple question. The vineyard owner, who is played by John Malkovich, pauses, presses his lips together, then opens them and ever so delicately, through sheer Malkovichian menace of enunciation, articulates the question and sinks in his fangs: “How do I not drive my father’s business into the fucking ground?”

Mr. Malkovich is onscreen only for a handful of minutes in the film, but his performance, at once sympathetic and terrifying, beautifully complicates an otherwise straightforward hagiography. The vineyard owner, the son of immigrants himself, can’t understand why Chavez is trying to ruin him, but what really hurts him is that his feckless, soft-handed son is so ill equipped to defend his family. “So often when you see something like this, the antagonist is so unlikely,” the actor, whose company Mr. Mudd produced Chavez, says. “And that always weakens the point of the film.”

When it comes to antagonists, there are few more likely actors than Mr. Malkovich. With a curl of the lip, a flick of the tongue, a slow and lizard-like blink of the eye, he conveys tremendous potential energy under the surface calm. The rage is almost entirely latent, the capacity for violence implied rather than demonstrated, which makes it all the more chilling. His performances as the louche libertine Valmont in 1988’s Dangerous Liasions or the capricious Russian KGB gangster in 1998’s Rounders made his name synonymous with slippery, insinuating villainy. Onscreen, his smallest gestures and most offhand comments can bristle with malicious intent, so much so that David Letterman once did a “Top Ten List of Things that Sound Creepy When Said By John Malkovich,” as performed by John Malkovich. (“No. 5: Nougat!”)

But talking about Chavez, and his upcoming TV series Crossbones, over breakfast at Gemma in the East Village, the actor comes across about as sinister as a glass of milk. Laconic, yes. Understated, definitely. Wryly self-deprecating, sure, but utterly polite, sincere and generous with his time, evincing nary a smirk nor cocked eyebrow. The most provocative aspect of his presentation is his outfit, a light blue suit with a blue sweater, the pattern of which matches the pattern on his tie, and a floral-printed shirt, also blue. Over the course of our conversation, he calls himself “an idiot” and “unremarkable in every way.” He says he’s nothing like the characters he has played, least of all, perhaps, “John Malkovich,” in the film Being John Malkovich. If anything, he says, he’s probably most similar to Lennie, the mentally disabled ranch hand in Of Mice and Men.

“I think maybe I got a reputation as a cold intello,” he says. “But, you know, nothing could be further from the truth. I’m sure to some extent people confuse roles I play with me. I prefer jokes myself.”

There is the temptation, of course, to read this disavowal as a joke. (Would a country bumpkin really use French slang for “intellectual”?) But his best friend and producing partner, Russell Smith, who has known Mr. Malkovich since they were in college together, echoes Mr. Malkovich’s self-description.

“There are a lot of perceptions of John, and in a weird way, they’re all wrong,” Mr. Smith says. “He’s a lot funnier than people think. He’s a lot more normal. He likes to watch TV, he likes basketball, he knows the events of the world. He’s not someone sitting around in his own world making macramé.”

When it is pointed out that Mr. Malkovich does, in fact, do needlepoint and knits, Mr. Smith clarifies: “He learned to do a little knitting around the same time he was caning chairs for Places in the Heart [the actor’s first film, for which he was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar]. He draws, he paints, he can get dirty and repair things, he gardens. He speaks beautiful French. He’s a Renaissance man.”

A Renaissance man, perhaps, but a self-made one. Talk to him about his childhood, and you get hints of the tremendous effort it must have taken to transform himself from an overweight, bullied, academically mediocre child into a soigné sophisticate holding the world at bemused reserve. Mr. Malkovich grew up the second son in a family of five in Benton, Ill. His mother was the editor of the town newspaper, and his father, a former paratrooper, edited a conservation magazine. Mr. Malkovich says he was at once dreamy and outgoing, chubby and athletic (as a teen, he lost 70 pounds on a Jell-O diet) but ultimately “just a little kid in a little town in the heartland … a very normal little boy.”

A formative influence was his older brother, Danny, who would later inspire his performance of Lee, the violent older brother in the Sam Shepard play True West.

“If you’re 9 years old and you’re home watching a movie about John Philip Sousa because you play the tuba and your brother comes home and jumps on you and spits on you, there’s not a lot of ways around that besides confronting it.”

As an adult, he says, he has learned to defuse situations, which wasn’t the image he had earlier in his career. (An oft-told Malkovich tale from the old days features the enraged actor scaring off a stalker with a bowie knife, another a punched-out bus window.) He insists his capacity for violence is overstated. “There are different categories of anger. Can you call it up or just pretend to? I’m not an angry person. … Most people who know me wouldn’t describe me as having a bad temper.” He acknowledges, though, that he is able to summon that childhood rage when it suits him. Mr. Smith says when fans approach the actor in public, “they have a hand up in defense, like, he might tear my arm off but I’m going to say this anyway. He has this soft voice, he’s a big guy, bigger than a lot of actors; he’s great at the quiet menace.”

Mr. Malkovich reconciled with his brother when they were older. He says Danny remembered their childhood differently. “To my brother, it was all a fantasy of mine. He was Wally Cleaver in his mind. He thought that I just had a bad temper and that’s why they called me ‘mad dog’ and my temper was always completely unprovoked, unwarranted, and nobody understood it.” His voice is quiet yet edged with steel.

Danny died in 2011, at the age of 59, one year younger than Mr. Malkovich is now. “Like a lot of complications in life, I loved my brother very much,” the actor says, his eyes softening with the suggestion of tears. “Of course, it would be nicer to say he was a terrible person, but life generally isn’t like that.

Mr. Malkovich attended Eastern Illinois University, and supported himself singing and playing guitar in bars and coffeehouses. (“I had a nice voice, a few billion cigarettes ago,” he says.) It is possible to see a video of him singing, improbably, Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah on a Russian TV show, a performance he claims his friend, the Lithuanian actress Ingeborga Dapkunaite, talked him into.

“I’m sure she told me, ‘You have to go on and sing something,’ but I’m sure I didn’t hear it or thought I would be somehow immune. As it turned out, when you go on it, you have to sing something,” he says. He has performed in operas, which he loves and says he would like to do more of, if it weren’t so impractical: “My agent would just go berserk, because, you know, they want you to do Spider-Man, and you have an opera date in Turkey.”

After leaving college a credit shy of graduation, Mr. Malkovich moved to Chicago and joined Steppenwolf Theatre alongside Gary Sinise, Joan Allen and Glenne Headley, who he later married. When the company’s production of True West moved to off-Broadway, the Times called his performance “an acting hole-in-one.” Film roles, along with the part of Biff in Death of a Salesman, on Broadway, soon followed. Then came Valmont in Dangerous Liasions opposite Michelle Pfeiffer, a divorce and the Bernardo Bertolucci film The Sheltering Sky, where he met Mr. Bertolucci’s then-assistant Nicoletta Peyran. The couple moved to the south of France, had a son and daughter and were living a quiet, contented life when Mr. Smith sent the actor a script for a film written by Charlie Kaufman. Mr. Malkovich liked the script but wanted to direct it himself, with a different actor playing the lead. Mr. Kaufman said “thanks but no thanks,” which is how the actor went from being John Malkovich to Being John Malkovich.

In the film, people pay to go down a portal into the actor’s brain for brief stretches. As John Malkovich, the experience of ordering towels from a catalog or eating leftovers from the fridge is so transportive soon the actor has to fight to retain his own headspace. Just as his old theater friend Gary Sinise will be forever known as the legless Lieutenant Dan from Forrest Gump, the movie came to define the man. His obituary headline practically writes itself.

He says he doesn’t regret doing it, though he understands why people think he might.

“It was certainly something I thought about: How will this fuck up my life? But actually, it didn’t make any difference whatsoever. What’s funny is how prescient the film was, totally unrelated to me. Pretty soon after that, everybody was taking a ride in everybody’s brain.” He inclines his head toward a busboy. “The waiter goes on Gawker or Dlisted or Page Six, you’re constantly photographed and listened to, there is the absolute disappearance of even notionally the idea of privacy.”

The actor and Ms. Peyran moved back to the States from France in 2003, following a dispute over taxes. Then in 2008, Mr. Malkovich returned from directing a play in Mexico City and hosted Saturday Night Live. The next night, still on SNL time, he was up late browsing the Internet—“a literary blog which had nothing to do with anything”—and saw a photo of Bernie Madoff in handcuffs. The actor had recently consolidated all of his investments with Mr. Madoff at his business manager’s advice. “I just kind of …” He sits back and does a perfect take of realization, his expression changing from incomprehension to understanding to a kind of amused resignation, as though on some level he expected this all along. “I said to my partner [Peyran], who was in bed already in our house in Cambridge—I said, ‘Listen, I think we have some problems. I’m going to go out and get a pack of cigarettes. I’ll be back in a minute.’ She said, ‘Don’t smoke!,’ and I said”—and there it is again, that Malkovichian italicization—“be back in a minute.”

The actor blames himself. “Of course, I was so dumb for allowing it, because, what is it he was supposed to be doing? I never really got it.” He cut back on his expenses, made some strategic career decisions and now has a philosophical attitude about the experience. “It’s hard for me to see myself as in any way a victim,” he says. “As an idiot is never hard, but as a victim, not really.” He was lucky, he says, in that he has always been able to get work. The following years brought those operas, small films for his production company—“tiny things, which could not even in a filmmaker’s wildest delusions be seen by more than a dozen people”—theater directing in France and bill-paying parts in Red, Transformers and Red 2.

Which brings us to Blackbeard. In Crossbones, a 10-part series that premieres on NBC in May, Mr. Malkovich plays the legendary pirate, complete with cravat, earring and flowing white locks. Blackbeard, who allegedly wore lit torches under his hat to scare enemies yet has no recorded murders to his name, relying on implied threat to impose his will, is well within Mr. Malkovich’s wheelhouse. The actor, who has not seen any of the finished episodes, will simply say that he found the experience quite pleasant in that it allowed him to stay on location (Puerto Rico) for almost six months, the longest he has been in one place since 1987.

Mr. Malkovich recently did an “Ask Me Anything” for the website Reddit, where he came across as wry, modest and game for anything, including recording the outgoing message for a fan’s phone. (“Hello, this is the answering machine for Benjamin. You know, he has so many friends, it’s going to be very difficult for him to get back to you.”) Commenters lost their collective minds (“I did the smart thing and just legally changed my name to Benjamin”), but the online performance is in keeping with the actor’s lack of investment in his public persona.

Whether an act of willed self-negation or, more simply, proof that in his most indelible roles he is just doing his job, which is to say, acting, Mr. Malkovich seems to have settled on a comfortable perch halfway between acceptance and resignation. If he has no compunction about playing a pirate on TV, he also takes no pride in his achievements on stage and screen. “You did something people liked in 1988. Is that going to make today’s work good? I don’t think so.”

Crossbones is set in the year 1715, three years before Blackbeard’s death. Does playing a man near the end of his life give him pause? “I don’t really think about a legacy,” he says. The man who claims to prefer jokes to machinations seems to find life the biggest cosmic joke of all.

“I was here, and then I’ll be gone,” he says, without a hint of malice but, perhaps, just a suggestion of that famous Malkovich insouciance, a verbal shrug. “I don’t really care.”