Mark Manders: 'My work is always totally silent'

Sponsored Content | Zeno X Gallery

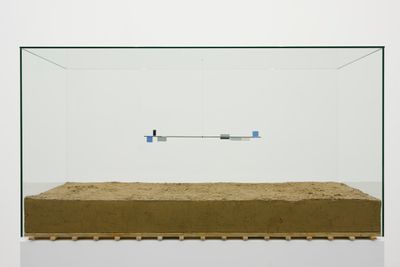

Mark Manders, Short Sentence (2021–2022). Painted bronze, various materials. 32 x 288 x 135 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery. Photo: Peter Cox.

Mark Manders, Short Sentence (2021–2022). Painted bronze, various materials. 32 x 288 x 135 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery. Photo: Peter Cox.

There is a sense of estrangement in Mark Manders' works. An estrangement from time and place, but also a distancing from the artist—a persona that Manders positions as a fiction in the spectator's mind.

In 1994, Manders wrote about 'The Absence of Mark Manders', referencing his early work, Inhabited for a Survey (First Floor Plan from Self-Portrait as a Building) (1986), in which he began to construct the idea of a self-portrait made of objects—in this case, the floor plan of an imaginary building formed out of pencils, pens, and paintbrushes.

The artist becomes, according to Manders, 'someone who disappears into his actions. He lives in a building that he continually abandons; the building is uninhabited, in fact.'1

Like many of Manders' works, Inhabited for a Survey is subject to hidden potential, here embedded with the idea of every word created by humans in a book with no beginning, nor end—one that cannot be seen or read.2 This elusive self-portrait serves as a framework and running motif for Manders' concept-driven practice.

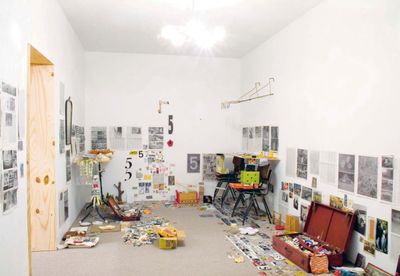

In addition to drawing, Manders primarily works with sculpture, depicting scenes that seem to function as interludes, before or after an action has taken place. A case in point is his 2002 work for Documenta 11 in Kassel, Reduced Rooms with Changing Arrest (Reduced to 88%), which incorporates both a sense of precision and ambiguity.

A figure is doubled on a table with slight variations as if to index the passing of time. There are three reconstructed 'sand rooms', an escape machine with two stylised dogs, a kitchen with an almost-still stream of water running from its faucet, and a glass-encased miniature garden in black featuring a cat split in half.

More than objects, Manders sees his installations as structures of thought—forms that originate in words or definitions. This is a process that is not always apparent to viewers or intended to be legible.

There is an element of the uncanny in arrangements such as the mouse strapped to a fox sculpture with a belt (Fox/Mouse/Belt, 1992–3), or the sculpture of a human femur attached to a coffee cup with a sugar cube suspended between them (A Place Where My Thoughts Are Frozen Together, 2001).

Both are comments on the nature of containment, and the former was shown as part of Manders' presentation for the 2013 Dutch Pavilion, Room With Broken Sentence, at the 55th Venice Biennale.

Among the arrangements that comprised the Pavilion were sculptures of an armless figure and head with Neoclassical leanings, bifurcated by wood planks. Nonetheless, it is difficult to categorise Manders' work or pin it down to a particular genre within art history.

In his solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo last year, The Absence of Mark Manders (20 March–22 June 2021), Manders continued to configure a fictional yet seemingly abandoned universe that alludes to incompletion, and the artist's departure. As Manders puts it: 'After all, what am I? A human being who unfolds into a horrifying amount of objects and language by means of very precise conceptual constructions.'3

Manders is a writer—armed with his own publishing house Roma Publications—but he sculpts his materials and objects with language, stringing them together like wordless forms in unfinished sentences.

On the occasion of his solo exhibition at Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp (3 September–15 October 2022), the artist shares his approach to freezing thoughts in sculptures that transcend time and place.

NKWhat drew you to sculpture in the very beginning? Is it the same thing that sensitises you to spatial languages and room-sized installations?

MMWith sculpture, you can record and freeze your thoughts. I really liked the idea that thoughts can become frozen objects that you can treat like language. You can speak with objects. Make sentences. And rooms can form sentences.

You often work with scale and duplication. I'm thinking about the fallen monument Tilted Head (2019), your doubling or even tripling of figures such as the three differently sized dogs in Abandoned Room, Constructed to Provide Persistent Absence (1992–2010), your reductions of objects to 88 percent of their original size, or Room with Fives (1993–2001). What is the significance of these precise measurements?

MMScale is very important. It defines how your body relates to an object. In my large installation at Documenta 11, Reduced Rooms with Changing Arrest (Reduced to 88%) (2000–2002), I also wanted to reproduce reality. So these rooms are like three-dimensional photographs on an 88-percent scale; you feel slightly bigger when you enter them.

NKTo a writer, your work can be seen as prompts for fiction or dream-like scenarios. While you've hinted that you don't like to dictate a narrative, what kind of stories are you trying to tell, however abstract?

MMWell, the rooms and works are totally frozen in time. They are like stage sets that are left behind. You can see clues of someone thinking.

NKYou've poignantly written, 'sometimes I try to make sculptures that are almost impossible to carry away in your mind.'4 What makes them impossible mental images?

MMFor some works, scale, dimensionality, surface, colour, and placement are so important. They become very difficult to carry away in your mind. When the work becomes a memory, it's something else.

NKIn A Place Where My Thoughts Are Frozen Together (2001), a femur becomes the support structure for a coffee cup, questioning the evolution of its use value for humans. I suspect there is a comment on the human-object relationship here, which you have articulated beautifully as: 'How an object outside your body can spark what you think.'5 What are your thoughts on object-oriented ontology, if any?

MMI think that if you place a certain amount of very specific objects in a certain order, it will say something about our minds and lives in relation to our death.

NKI want to talk about the halving or doubling of figures, whether human, as in Unfired Clay Figure (2005–2006), or animal, as in Nocturnal Garden Scene (2005). These concrete divisions appear to be comments on space and time. Like a freeze-frame of a moving moment. Can you say more about these physical ruptures in form?

MMWhen you live and think in a totally frozen world, it is logical that you try to find ways to put more time in one single room.

NKYou've likened your heads to musical chords. What role does sound play in your work?

MMMy work is always totally silent. For me, these heads are like chords. They are compositions of verticals. If you make one vertical shorter or thicker, or if you change the colour, the head becomes a totally different chord.

When I make bigger shows, I like to think about a musical composition, how the rooms follow each other and how they make different sounds.

NKSometimes your sculptures have unfinished textures like wet or unbaked clay, your figures are armless, and although you want viewers to feel as if they have entered an abandoned space, everything about the work must be fine-tuned in your mind. What leads you to create these in-process—or just-finished—impressions?

MMAll the works exist in one big super-moment and are installed to appear to have been suddenly left behind. The great thing is that these works speak to each other.

NKYou've often spoken about the moment and capturing it in the here and now. While your works are usually motionless, they lead viewers to imagine what came before and after.

But in Isolated Bathroom (2003), there is a sense of endlessness in the continuous motion of the water, or perhaps a never-ending present that is just past. Was this intended? How about Kitchen (Reduced to 88%) (2002), in which you regulated the water, so it appears to be still and material?

MMYes, these are two moments that have a more complicated relationship with time. In Isolated Bathroom, the water moves a fake ballpoint pen that hangs above a hole. In Kitchen (Reduced to 88%), the water feels frozen and falls into a perfectly round hole with edges as sharp as a stainless-steel knife.

NKLanguage is a significant part of your practice, though it is not part of your sculptures, per se. Rather, it serves a supplementary function as adjoining text or titles.

In the few cases where you do include language, it feels nonsensical as with the fake newspaper with all the possible English words in Ramble Room Chair (2010). As someone who is so literary, where does the impulse to abstract language come from?

MMI just finished a work that is important to me. It is called Room with All Existing Words (2005–2022). At the ceiling of the entrance, you can find the complete group of my newspapers, which contains every single word that exists in English.

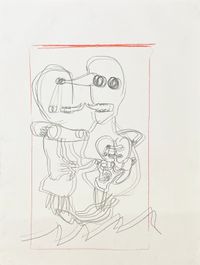

The other part of the room is dedicated to one word that is kind of forgotten and not really used: Skiapode. A word for a strange, failed myth. I made many different images of Skiapodes. They seem to be from different periods, regions, and artists.

When I make bigger shows, I like to think about a musical composition, how the rooms follow each other and how they make different sounds.

I also made a fake Wikipedia website that will go online soon. It reflects a desire to give a forgotten word a new, but fake life. I worked on this room for many years, and it will be shown for the first time in Antwerp.

I like that the word 'chair' has so many different forms. It is great that the word Skiapode is also richer now. It feels logical that humans made chairs, but it is very strange that we made images of Skiapodes. It tells us something about our mind.

NKIf we go back to your 1986 floor-plan work made of writing tools, Inhabited for a Survey (First Floor Plan from Self-Portrait as a Building), which has branched into other iterations, you delve into this need to abstract language in spatial terms.

You initially wanted to create a Borgesian, endless book about the self-portrait of a building before understanding the limitations of language. You now operate in the language of objects, arguably, allowing them to speak for themselves.

If your sculptural language of objects is situated between your intention and the viewer's interpretation, does it matter where the object conceptually originated from?

MMWell, the object hangs between us. Between me as a maker and you as a viewer, who needs the idea that someone made the object with an intention. In this way you can project your thoughts onto the maker and the object they made.

NKIs this extrapolation from the human figure—your self-portrait—to the fictional building linked to the absence of Mark Manders? Or is it more about the sense of estrangement you place between yourself, personal details, and seemingly abandoned or lifeless objects?

MMI really want to dedicate my life to investigating the human mind. I am amazed by where our minds can take us. For me, this is a fascinating and meaningful journey.

At the same time, it is sometimes scary when you see how far minds can drift away from reality. Especially now, when you see smart and bright people starting to believe in weird conspiracies with no way out of their tunnel.

NKCan you say more about Finished Sentence (1998–2006) and Finished Sentence (August 2007) (2003–2007)? They seem to map out a movement of interconnected objects.

MMI was reading a story by Kafka and I became jealous that he could really write with words. How easy he made it seem. Then I rushed to the supermarket. My goal was to look for an object that was for sale that I could use as language.

I discovered that you could use teabags in a kind of binary way. You can put a teabag on the floor, or the teabag and the label on the floor. You can make endless combinations and beautiful word-like rhythms. These works look a bit like musical instruments that try to speak to us.

NKWhat's your process like? Do your sculptures begin as drawings, images, or ideas? I know that you often work on sculptures simultaneously.

MMThe Skiapode room took me many years to make. In the nineties, I made a room with only fives. Since then, I thought about making another room dedicated to a single word. It took that much time. I have many ideas that are growing, and of course, they feed one another.

NKI read that some works take months while others take decades. How do you decide when a work is finished?

MMYeah, that is a strange aspect of my work. Sometimes it takes you more than 20 years and sometimes just a day.

NKYou've mentioned that there is no distinction between your works from the past and present, as they belong to the same timeframe. But surely you can detect changes in your work over time, and instances of failure?

MMMy work develops slowly. Failure is an important aspect in my studio. And desire. But not too much.

I have so many ideas lying around my studio that are not yet good. They fail, but they give me a lot of energy because I am confident they will grow into fantastic new works.—[O]

1 Mark Manders, 'It is disappointing that we seem to observe the world as through a membrane': http://www.markmanders.org/texts/english/it-is-disappointing-that-we-seem-to-observe-the-world-as-through-a-membrane/.

2 Manders, 'Inhabited for a Survey (First Floor Plan from Self-Portrait as a Building': http://www.markmanders.org/works-b/inhabited-for-a-survey-first-floor-plan-from-self-portrait-as-a-building/.

3 Manders, 'Drawing with Shoe Movement / Two Consecutive Floor Plans from Self-Portrait as a Building (May 21, 2002)': http://www.markmanders.org/works-b/drawing-with-shoe-movement-two-consecutive-floor-plans-from-self-portrait-as-a-building-may-21-2002/.

4 Manders, 'Nocturnal Garden Scene': http://www.markmanders.org/works-b/nocturnal-garden-scene/.

5 Manders, as quoted from Walker Art Center: https://walkerart.org/press-releases/2011/mark-manders-parallel-occurences-documented-a.