Behold the steamed bun! Extremely versatile and adaptable, the steamed bun has evolved throughout various Asian cultures, settling with the local meats, spices and seasonings to create a dish with multi-identities in different countries. My own memories of steamed buns reach far into the edges of the mountains of Himachal Pradesh, where my parents, with my toddler self in tow, had been invited into the homes of the folk artists they were filming. Seated on the floor, steamed pork buns being passed around in a small bamboo steamer, with a bowl of clarified butter and hemp seeds to dip the buns in. Later, I would find the dish was called ‘siddu’ in the Pahadi dialect. The memory of the taste has stayed with me, the lightness of the bread, the surprise saltiness of the meat, the oiliness of the sauce; the true KinderEgg™ of food. While the cultural permutations of steamed buns could make a research project in itself, the star of today’s gustatory show is baozi or Chinese steamed buns and their journey from China to Queens.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-480052548-57d471df3df78c58334b32ae.jpg)

A History

Baozi is a type of steamed bun with a filling. It has an airy breadlike texture and is usually stuffed with meat or vegetables, and garnishes such as green onion, sesame, coriander and leeks. It is served with dipping sauces and the meat is usually seasoned in soy sauce, chili oil and garlic. It can be eaten at anytime of the day but is usually eaten for breakfast.

The history of baozi stems from its inseparable relationship with mantou, a fluffy, steamed bread that can be considered the predecessor of baozi. In the eastern Zhou dynasty in 771 B.C. people were already steaming fermented flour dough, calling it Yi food. The invention of both are attributed to one man, Zhuge Liang. It is a tale of legendary proportions, beginning with Chancellor Zhuge Liang defeating the southern barbarians, and coming across the treacherous and stormy Lu river with his men. In order to cross this river, the locals advised the army to sacrifice human heads to the river.

Interestingly enough, according to Ming Dynasty scholar Lang Yin, the original word for mantou was ‘barbarians head’ and during the Three Kingdom Period barbarians used to use human heads to worship gods. Chancellor Liang could not bear to sacrifice innocent human lives , and instructed his men to kill some of their animals and to stuff the meat into flour dough and steam them in round shapes. Those meat buns were then tossed into the river as fake heads to appease the river gods, who fell for this trick and the raging river ceased.

Another, perhaps truer variation is Chancellor Liang and his men were confronted by enemies across the river. In order to pass safely, the men demanded Chancellor Liang behead fifty of his men. To avoid this, Chancellor Liang instructed his men to fill the dough with meat and exchanged those as ‘heads’.

Variations

There are plenty regional variations of baozi as well as newer variations for changing cultural and diet demands. From Shanghai, there is xiaolongbao , smaller in size, with thinner dough wrappers. Pan-fried baozi with sesame and spring onions also are representative of Shanghai tastes. In Guangdong, there is the famous char siu bao with its typical char siu (‘fork-roasted’) style barbecued meat. The baozi is cracked to emit the scent of char siu meat. In Tianjin, there is goubuli baozi which has its own characteristic way of folding. Every baozi has eighteen wrinkles. Sichuanese cuisine has the chengdu pork baozi which is known for its unique filling of fresh pork mixed with deep fried pork, peppercorn, ginger sauce and steamed in chicken stock and cooking wine. Other non-regional variations include sweet steamed dumplings with fillings such as red bean, sugar or custard and vegetarian versions with tofu.

Preparation & Ingredients

The preparation of baozi is a two step process. First the dough is produced for the mantou, and while it rises, the filling is prepared. The dough is made with wheat flour, activated yeast, baking powder, shortening or lard and sugar and salt. The bun owes its fluffiness to the presence of both the leavening agents. The dough is stiff and allowed to rise for an hour or until it doubles in size.

Usually, the meat used in the filling is pork. Basic additions include scallions, cabbage or mushrooms. The filling is seasoned with garlic, ginger, rice wine, soy sauce and sesame oil.

Recommendations for baozi folding, is twisting pleats into the top of the dough. Baozi makers advocate for twelve to thirteen pleats.

In the Han dynasty, stone mills became popular and people started grinding wheat flour, which became one of the ingredients for baozi . Imperial courts decreed that the bread used for worship should be mianqi bread, which required yeast to make it light and fluffy.

Many traditional Chinese ingredients were foreign imports from the West; sesame,peas, onions and coriander were brought through the Silk Road from Bactria during the Han Dynasty in 206 B.C. to 220 A.D. However, China has a long history with meat, dating back seven thousand years to prehistoric times. In the Yin Dynasty (1556–1046 BC), pig, sheep, cattle, and even dog were served as precious gifts for the nobles and the royal family. During the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), there was a large growth in the preparation of various meat products such as cured meat. Today, pork still stands as the most widely consumed meat in China.

Migration of Baozi

The Chinese baozi has had an influence in Taiwan and other southeastern Asian cuisines due to migration. In Malaysia they have pau- steamed buns filled with curry beef, chicken or potato. Due to the largely Muslim population in Malaysia, the fillings are halal and contain no pork. In Indonesia they are known as bakpao and street variants include chocolate, marmalade and sweet potato. The Japanese variant is known as nikuman.

So naturally, it comes as no surprise that the traditions of baozi were carried by the many Chinese immigrants who made their way to the New World and settled in New York City, bringing their food with them.

Chinese sailors began settling in lower Manhattan as early as the 1830’s. The first wave of Chinese immigrants included mostly peasants and workers and in Queens, the first vegetable farms and hand -laundries were operated by the Chinese in the 1880’s. However in 1882, a law prohibited Chinese immigration and naturalization until the Immigration Act of 1965.

In New York City, the highest concentration of Chinese populations can be found in Chinatown and Flushing. Most of the Chinese population in Chinatown is from the Taishan and Guangdong areas, while the population in Flushing includes Chinese mainlanders who went to Taiwan after 1949. Taishanese and Cantonese are dialects spoken in Chinatown and Mandarin, Cantonese and Taiwanese are dialects in Flushing.

Flushing, Queens, where I found the baozi I will later review, was originally named Vlissengen and started out as a Dutch colony in 1645. The notable feature of this neighborhood was its residents were allowed religious freedom, and Flushing was known as the birthplace of religious freedom in the New World. In the 1970’s, the demographic began shifting from white to Mandarin-speaking Chinese immigrants who had trouble settling down in the Cantonese-speaking areas in Manhattan.

Chinese immigration and foodways predominantly began during the Gold Rush, on the West coast by immigrants from the Guangdong province. The first documented Chinese restaurant opened in 1849 as the Canton Restaurant. By 1850, there were five documented Chinese restaurants in San Francisco. This increased an import of Chinese food to the West Coast and with the advent of the railways, Chinese food reached New York City.

After the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, there were only fourteen Chinese restaurants in San Francisco, however, restaurant owners became eligible for merchant visas in 1915 leading to Chinese restaurants becoming instrumental to immigration.

As of 2015, there were 46700 Chinese restaurants in the United States. Baozi is a popular option that appears as “Steamed Meat Bun” in various Chinese restaurants. In the age of Instagram, baozi has become quite a trendy food, not only owing to it’s amazing flavors, but also partly due to its photogenic qualities: the daintiness of the flour pleats against the aesthetic of a bamboo steamer dish, as well as its versatility towards experimentation and variation. Especially after the short animated film Bao, where a little steamed bun becomes alive and sentient much to the, its popularity has surged.

However, this brings its own issues. A Global Times editorial recently attacked Western-Chinese fusion food that floods expat-restaurants in Beijing, the bazzoza, a fusion of pizza ingredients inside steamed bread. The article claims “It combines Western with Chinese fast food while ridiculing both food traditions for the sake of a marketing gag for expats with little or no culinary background”

Red Bowl Noodle Shop Review

A strange sequence of events brought me to Main Street, Flushing. In the middle of processing my application for a work permit on my international student visa, the international students office decided my two passport pictures from the convenience store would not make the cut, and that I had to have my pictures taken by a specific photographer in Flushing. I made the trip down on the 7 train, (not so terrible because of the scenic views at sunset) and had my pictures taken (which surprisingly came out really well) and reveled in the bustling chaos that is Flushing, with its fruit markets on the pavement reminding me of home and stalls of roasted chicken and fermented meats and sauces and some vendors and bargainers. It was the spirit of New York exemplified. It was windy (I’d even packed my hairbrush for the photos) so I decided to find a spot to eat, telling myself it may make good material for the #foodways class (or an excuse to eat).

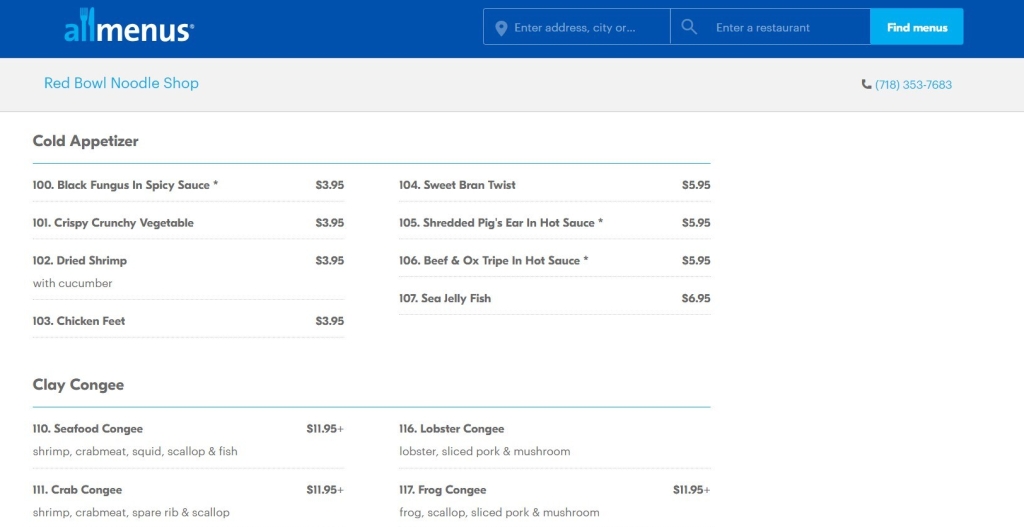

I stepped into Red Bowl, because it seemed to be doing good business and I liked the simple red graphics. It seemed small however it was quite large on the inside, with a takeout counter at one end, and a larger seating area with benches at the other. It seemed fairly busy, so I won’t begrudge the restaurant for slightly slow service. I was given complimentary jasmine tea. The menu had specialties such as frog, tripe and chicken feet as well as traditional Chinese dishes such as congee. I originally ordered the Pork Noodle Soup, intent on finding differences between it and ramen. I ordered the Steamed Pork Buns as an afterthought.

The soup itself was very different from ramen. No heavy bone broth, but clear broth, with thin noodles, bok-choy and a GENEROUS cut of roasted pork, as well as half a boiled egg. The soup was seasoned with garlic, ginger, lemon and chilli, though I did add more sriracha and chilli oil as the thinner noodles do not soak broth like wheat noodles.

I do wish I’d eaten the buns first. Even so, when I bit into a bun I was pleasantly greeted by the faint sweetness and airy and cloud-like texture of the bun, and further in, the warm and spiced pork fat that has been steamed unto itself and cooked in its own flavors. There were scallions and coriander in the buns, which added sharper texture and a fresher taste. The meat itself was very soft, and dissolved almost as quickly as the fluffy bread. I could only get through two however, so I got the rest to go.

The real test however, came when I came home from a night out and ate half of the buns cold and unheated. They still tasted good straight from the fridge, the flavors having infused for longer. What really set these buns apart was the balance between the meat and bread, it wasn’t doughy, and the meat too was seasoned well in flavors of salty soy sauce, earthy sesame and piquant garlic and chili.

The baozi in front of my Polaroid wall

| Rating | Stars (1-5) |

| Food | ★★★★★ |

| Service | ★★★★ |

| Cleanliness | ★★★★★ |

| Ambience | ★★★ |

| Large groups | ★★★★ |