Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Excerpted from Mark Harris’ Mike Nichols: A Life, out now from the Penguin Press.

Mike Nichols had one phone number in his pocket, and it was all he needed.

It was the autumn of 1957, and Nichols and his comedy partner Elaine May were in New York City with $40 in borrowed money, the names of a couple of friends willing to let them sleep on their sofas, and a single contact: Jack Rollins, a talent manager who could book singers, comedians, and novelty acts into town. They got an appointment, visited Rollins in his small office, and did 15 or 20 minutes of material. They asked Rollins to suggest a first line and a last line and told him they would invent a scene for him on the spot. “[I thought] my God!” Rollins said. “I am finding two people who are writing hilarious comedy on their feet.”

It was done. They were in. “They were remarkable,” Rollins said. “They were complete. I knew they had something odd and wonderful, but I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.” That day he took them out to lunch at the Russian Tea Room and signed them. They were relieved when he picked up the check.

In the late 1950s, supper-club culture was still a thriving New York scene, with full houses, big names, and a cadre of columnists covering every up and down, and Rollins got them an audition at one of the most popular of the East Side cabarets, the Blue Angel. The owner, Max Gordon, was as impressed as Rollins had been, and offered them a booking in two weeks. Politely, Nichols explained that they needed money sooner than that. So Gordon gave them a second, temporary gig—starting right away, they could play his downtown club, the Village Vanguard, until the spot at the Blue Angel opened up.

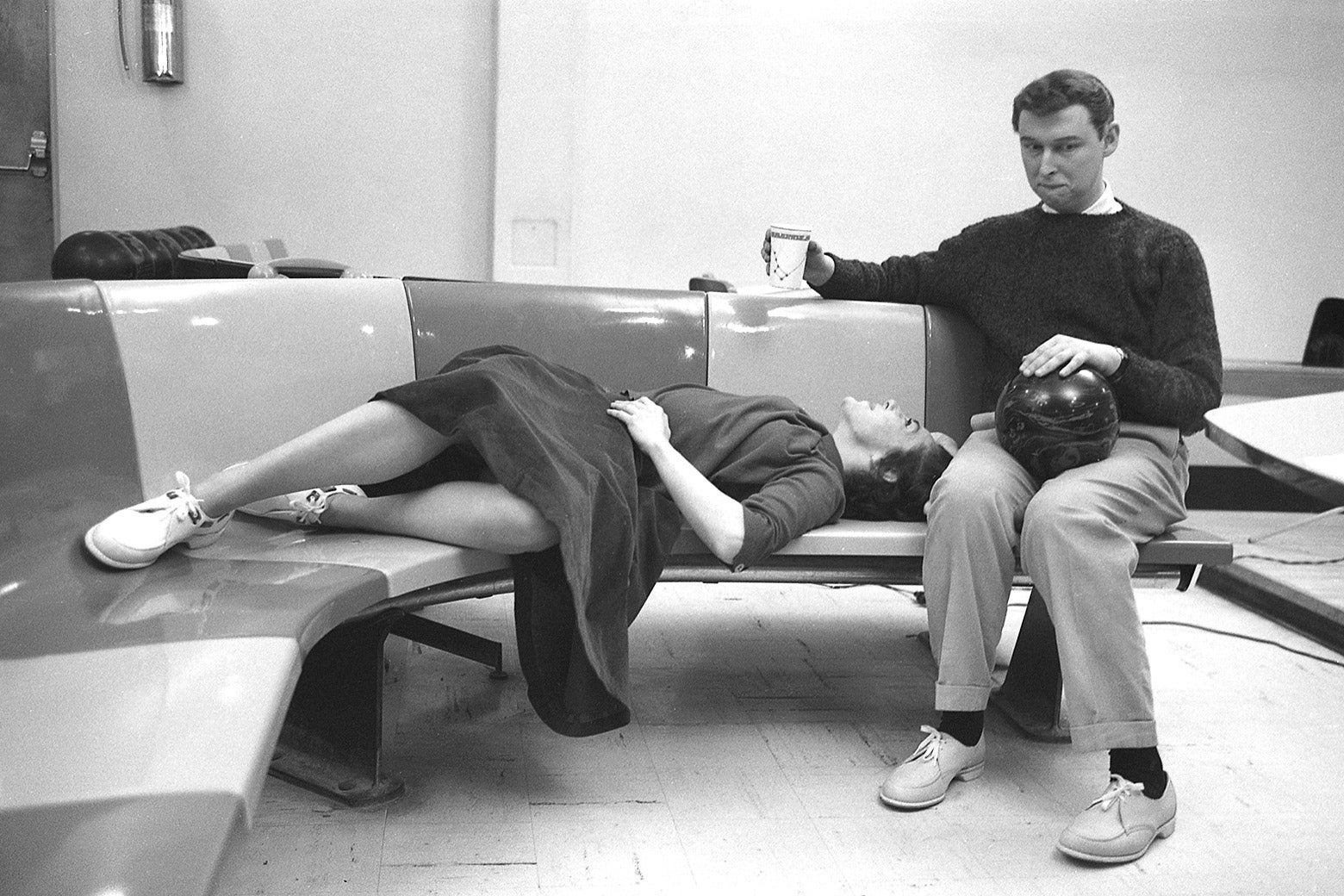

The Vanguard had been a mainstay of the West Village for almost 25 years, a casual watering hole for a young crowd of locals, beatniks, poets, potheads, and anyone else who liked jazz combos, blues singers, and cheap drinks. It bore a close resemblance to the bars Nichols and May had played in Chicago, and was a comfortable place for them to warm up. They started there in early October as the opening act for Mort Sahl, whose style of casually delivered topical humor—the equivalent of a live late-night monologue—had brought him a measure of success in the previous few years. Every night, Sahl would stroll out onstage, usually in a red V-neck sweater and with a folded newspaper under one arm, and riff on the day’s events. It wasn’t Nichols’ style, but he saw how effectively Sahl worked the turf; he packed the Vanguard every night, and thus guaranteed his two novice openers a big audience. They came up with a short set tailored to the small space—starting with a sketch called “Teenagers,” set in a parked car at night, that could be done with just two high stools on which they sat side by side.

After “Teenagers” and maybe one more sketch (or not, depending on Sahl’s level of impatience), they would do what they’d done to impress Rollins: They would ask the audience for line suggestions—and for a particular literary style, from Shakespeare to Tolstoy to Clifford Odets—and, for their big finish, they would improvise a scene in that writer’s style. The laugh when they got to the last line, with the audience delighted to discover how they’d made their way there, was a perfect high on which to end. “The trick was, we had both read everything,” May says. “The toughest thing was if they gave us an easy one, because we hadn’t read the easy ones. But they would try to stump us, and the more they did that, the easier it got. Greek plays were easy. Ibsen was easy. Harold Robbins would have been hard, because we hadn’t read him.”

At the Village Vanguard, they were an instant sensation—so instant that the audience on the second night already included repeat visitors. Sahl was in danger of being upstaged, and he knew it; in the second week of their Vanguard run, he stepped in a couple of times just as they were about to go on and canceled their set, telling them the crowd was already primed enough for the main attraction.

They hurtled toward their opening at the Blue Angel with barely a moment to rearrange their lives. Both of them were trying to find apartments—May would soon be able to move both her mother and her daughter to New York to live with her, and Nichols was on the phone to his wife, trying to get her to tie up loose ends in Chicago and join him. Otherwise, they hadn’t touched base with anyone, a fact of which Nichols was reminded when the phone rang and the voice at the other end, with icy precision, said, “Hello, Michael. This is your mother speaking. Do you remember me?”

“I said, ‘Mom, can I call you right back?’ ” Nichols remembered. “And I called Elaine and said, ‘I have a new piece for tonight,’ and I told her the first line. She said, ‘Oh! Say no more!’ We did it that night. We had talked about it no more than that and the way we did it stayed forever. I told my mother it was Elaine’s mother, she told her mother it was my mother … it was very liberating!” The sketch, known as “Mother and Son,” was a six-minute phone conversation between Nichols, as a brilliant rocket scientist in the middle of a launch, and his emotional assassin of a mother. (“Arthur, I sat by that phone all day Friday and all Friday night and all day Saturday and all day Sunday. Your father finally said to me, ‘Phyllis, eat something, you’ll faint.’ I said, ‘Harry, no. I don’t want my mouth to be full when my son calls.’ ”) It was a superb showcase for May, who made a feast out of lines like “I’m sorry I bothered you when you were so busy—believe me, I won’t be around to bother you much longer.”)

“Mother and Son” was part of their first performance at the Blue Angel in mid-October; they were initially a late-night act, for those who didn’t mind staying up and staying out. Two weeks later, Rollins said, “they were the hottest thing in the city.” As hyperbolic as that sounds, it wasn’t much of an exaggeration. Within days of Nichols and May’s Blue Angel opening, it became a badge of cultural cachet to say you saw them first, you saw them twice, you saw them in Chicago, you saw them downtown. Gordon realized that he’d stumbled upon gold; he quickly signed Nichols and May to a six-month contract. By December they had landed in the pages of the New Yorker. “Taking shelter from the damp one recent night, I wandered into the Blue Angel and caught their act. I enjoyed it so much that I’ve been back a couple of times since,” Douglas Watt wrote in his Tables for Two column. “Mr. Nichols, a fair youth with an alert and friendly mien, and Miss May carry on little dialogues … with something of the same delightful interplay characteristic of that splendid vaudeville team the Lunts; the bantering tone, the repeated phrases, the artful covering of each other’s lines—all these devices are present, and well-mastered.”

“New York is not only fashion-driven but fashion-obsessed—and we were stunned to become a fashion,” Nichols said. “We’d just been in Chicago, where people laughed if it was funny; if it wasn’t, they didn’t. [But] once [Watt] said we were like the Lunts, they laughed when we came out on stage.”

At the end of the year, Rollins got them an audition for Jack Paar, the new host of NBC’s Tonight Show. Paar agreed to try them out in front of a full studio audience during a rehearsal—essentially a camera test. It went poorly. The audience was used to stand-up comics, but not to the sly observational role-playing that had won over clubgoers. Nichols and May went into a routine, and when Paar sensed that they were starting to lose the crowd, he pulled the camera off them midsentence and said, “Do an improvisation, kids, and make it snappy.” They stumbled through an attempt, but they were rattled and thrown—and not invited to appear on the show.

Undeterred, Rollins booked them on the competition—ABC’s The Steve Allen Show—and on Dec. 29, 1957, Nichols and May made their national television debut. Allen introduced them as “a youthful duo … two young folks who [are] a pair of bright lights on the comedy horizon. Very clever,” and then the camera cut to them in their newly bought clothes—a jacket and bowtie for him, a long-sleeved black dress for her—sitting on stools in front of a microphone. The sketch wasn’t a home run, but over the course of its seven minutes, one can feel the audience gradually warming up as it catches on to a rhythm and style it hadn’t seen before. The two of them, relieved to be done, took their bows as Allen, in his businesslike way, said, “Elaine May and Mike Nichols, real great. We’ll have ’em back soon.”

Three weeks later, their lives changed forever. On Tuesday, Jan. 14, 1958, NBC’s popular program Omnibus aired a two-hour prime-time special called “Suburban Revue,” a series of routines, sketches, and songs built around a unifying theme. The show’s producer gave Nichols and May two slots. The special was a mess that never quite recovered from the irrelevance of its opening, a flapper-era song-and-dance skit called “The Gladiola Girl” that dragged on for 18 minutes with barely a smile from the audience. But Nichols and May were standouts; the laughs built steadily in both of their appearances, with the biggest of the night coming in “Teenagers.” Over the years, they had worked out their only extended bit of physical comedy—a long car-seat kiss during which all four of their arms flail and interlock as they negotiate the holding of a cigarette; after a long time, May pulls her lips away from his to exhale a cloud of smoke. When they did it on Omnibus, the audience exploded with laughter—as it did when, a few moments later, Nichols said to May, with imploring urgency, that if she let him go further, “I would respect you like crazy.”

“Everyone had said to Rollins, ‘Nobody will get them, they’re too intellectual,’ ” says May. “Well, everyone got us. We couldn’t believe it.” Nichols and May had had a “Who are they?” moment in front of mainstream America: They were literally an overnight success. “We did 20 minutes and just like that, we were famous,” said Nichols, who knew it had happened the second he read the first review. (He immediately woke May and said, “What do we do now?”) The trajectory that Rollins had mapped out for them—perhaps a few more appearances on Steve Allen’s show if they were lucky, plus steady work at the Blue Angel—was scrapped. In one step, they had cut straight to the finish line. They were no longer up-and-comers; they were stars. Rollins started planning an LP and a national tour; he would still put Nichols and May on TV, but now he was demanding $5,000 for each appearance—more than either of them had made in total during their last year with the Compass Players in Chicago —and getting it.

For the rest of his professional life, no moment would disorient Nichols as profoundly as the sudden, simultaneous arrival of wealth and celebrity did in the first months of 1958. He was 26 years old, less than six months past being fired from a minor comedy gig in Missouri, and had only recently been able to afford a new and slightly better toupee. The self that he would painstakingly compose in front of the bathroom mirror—“It takes me three hours every morning to become Mike Nichols,” he later told the actor George Segal—was a struggler, a striver, someone who had to put great daily effort into making himself just passable enough to blend in. Now, he said, “I had sharkskin suits and Jack Rollins calling us the hottest team in showbiz.” At the time, Nichols insisted that he saw “nothing operationally different in my life.” It couldn’t have been further from the truth.

From Mike Nichols by Mark Harris. Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Mark Harris, 2021.