If you want to put a face to the astounding rise of the French extreme right, which has taken Marine Le Pen to the brink of the presidency, you could do worse than Anthony Brozzu. With his thick glasses, neatly trimmed goatee, and sleeve tattoos, the 40-year-old runs a farm-to-table restaurant in the center of Arras, a small, charming city in Picardy. He’s a vegetarian, an environmentalist, and a first-time Le Pen voter.

“My grandparents would be rolling in their graves,” he said on Thursday, cleaning up the lunch run shortly before the Le Pen diehards began to descend on Arras for her final rally of the campaign. “But she’s changed. She’s not as fanatical. She’s extreme right, but nice.” Brozzu thinks Le Pen is right to emphasize France over Europe (he pays a premium over his competitors to buy local products for the restaurant), and thinks she’d be better for small businesses than Macron. Mostly, he says, he just wanted a change. “First woman president,” he said. “Why not? Elect a woman and maybe things change.” But he also thinks she’s right that too many immigrants to France just don’t want to assimilate.

Five years after losing to Emmanuel Macron by a two-to-one margin, Marine Le Pen has won converts like Brozzu by softening her approach. Her politics are still radical—she would quit NATO and maybe the EU, strip away immigrants’ rights, and ban the hijab from public spaces—but her mood is upbeat.

She trails the incumbent Macron by ten points in the latest surveys, and it would take a big polling error to see her triumph on Sunday. Still, she will take an outright majority in thousands of towns and a handful of regions, a result that would have shocked French voters two decades ago when her father, party founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, broke through to the runoff. In 2002, Le Pen père was considered so radioactive that President Jacques Chirac wouldn’t even debate him, and left-wing voters built a “Republican front” dam behind Chirac to give him more than 80 percent of the vote.

Brozzu’s drift right—he did not vote in 2017, he says—demonstrates two of the ways that Le Pen has managed to effectively “de-demonize” her party, her family, and herself. Le Pen got outflanked on the right during the primary by the journalist Eric Zemmour, whose rancorous campaign pulled in constant media coverage—and seven percent of the vote. Zemmour functioned as a kind of portrait of Dorian Gray for Le Pen, absorbing all the ugliest parts of her party’s reputation, including accusations of anti-Semitism, racism, and revisionist history. He even won over Le Pen’s own father, and her niece and onetime protégé, Marion Maréchal, to the tabloids’ delight. Brozzu thought Zemmour’s campaign was hateful and wrong, but he has no such reservations about Le Pen.

If Zemmour made her look moderate by comparison, Le Pen helped by shifting her focus from Islam and immigration to pocketbook issues. Instead of telling the French to read Camp of the Saints, the racist dystopian novel beloved by Steve Bannon, as she did in 2015, Le Pen now talks about her hobby, raising cats. “She’s not saying, ‘Let’s kick out the foreigners’; she’s dropped that,” Brozzu observed. The invective about foreigners in France that remains in the Le Pen platform—and there’s plenty of that—has taken a backseat to more abstract complaints about immigration policy and crime. But all of it has been superseded, for Brozzu and in the French media at large, by her focus on the rising cost of living and the arrogance of Emmanuel Macron. “Macron doesn’t like the French,” she likes to say.

Do the French still like Macron? Earlier this month, I went among the Macronists to the president’s campaign rally before the first-round vote. There is indisputably something a little lame about getting dressed up, chanting, and waving a flag for an incumbent centrist president. And yet there they were, 30,000 strong, armed with French and EU flags, chanting “one and two and five more years!” I sat between Souleymane Sarr, a shipping executive from Paris who has supported Macron from day one, and Hélène Chamouard, a paralegal and Macron superfan who had come with her 12-year-old son. Macron bounded onto a hexagonal stage (symbolic of France’s six-sided geography) and spoke in his measured, careful cadence for more than two hours about every subject under the sun: culture, retirement, terrorism, secularism, ecology, Europe, bullying, child abuse, and so on. When you only do one campaign rally, there’s a lot to get through.

On April 10th, in a first-round vote characterized by strategic voting on the left and right, Macron nevertheless improved his margins and outperformed polls. The Macronists I met like his intelligence, his competence, his leadership in Europe, his management of the coronavirus, his record on the economy, his realism about what it will take to preserve the French social model. What most unites them, though, is the feeling that things are pretty good right now. Voters feeling “satisfied” with their lives were twice as likely to support Macron versus Le Pen. And why not? France’s unemployment rate is at a 15-year low. The threat of terrorism has slowly receded. And the coronavirus crisis seems like ancient history.

But not everyone shares the enthusiasm. In the first-round vote, participation dipped below 75 percent for the first time in two decades. That sense of apathy is likely to be amplified in Sunday’s runoff, a rematch of the 2017 contest, one where Macron has lost his shine as a renegade outsider.

Indeed, the president’s five-year term has left many of his voters—whether they were enthusiastic supporters or reluctant dam-builders in 2017—feeling disenchanted, angry, or betrayed. A series of gaffes have contributed to the impression that he is a Napoleonic figure who might not know the cost of a croissant. When a man complained to him that he couldn’t find a job, Macron was incredulous. “Nothing? I’ll cross the street and find you one,” he retorted.

It’s partly Macron’s own fault that his opposition is stronger than ever. After promising at the start of his mandate to eliminate the extreme right, he and his ministers have parroted right-wing talking points on issues such as immigration, race, and religion. As Covid cases shut down French classrooms this winter, for example, the French Education Minister gave the keynote speech at a conference on wokisme. In an attempt to drain Le Pen’s support, they have wound up legitimizing her worldview.

The trend isn’t just rhetorical. “I’ve seen the evolution of Macron towards the center-right,” the right-wing former president Nicolas Sarkozy said last week. “Who can complain? Not me. Now that a large part of his ideas are the same as ours, we’ve got to support him.” Those right-wing policies have both alienated left-wing voters and created room for Le Pen to take up their concerns. On issues such as raising the retirement age, she is now running to Macron’s left, and polls show about one in five far-left primary voters will support her on Sunday.

In the frantic two weeks following the first round, Macron has made some effort to reinforce his left flank. He held a rally in Marseilles to focus on the environment, and softened his resolve on raising the retirement age to 65. The left-wing paper Libération put Macron on the cover, running away from the camera, with the headline, “Honey, I forgot the left!” But that version of the president was not on display at the campaign’s sole debate on Wednesday night, a technical, three-hour affair in which Macron sought to portray Le Pen not as unacceptable so much as unprepared.

When Le Pen talked about criminals, Macron didn’t bother to pinpoint the economic roots of misbehavior. When Le Pen reiterated her view that the hijab is a symbol of terrorist ideology that she would forbid in public, Macron responded by telling her, “You’re going to incite a civil war.” As if, like her other ideas, this one wasn’t so much amoral and intolerant as foolhardy and impractical.

To the extent there’s still a chance Macron blows his lead, it will come down to the decisions of left-wing voters who feel he’s treated them with contempt. At a café in Arras, I shared a table with Nicole Giraud, a retired substitute teacher with a stack of Trotskyist magazines under her arm. She decried Le Pen’s “barely disguised racism” and worried her election would set loose “packs of idiots” empowered to mistreat the country’s minorities. But this menace was not enough to get her to vote for Macron, whom she perceived as a candidate for billionaires and steward of an unethical policy towards migrants.

If you’re feeling flashbacks to the US presidential election of 2016, you’re not alone. What’s happening in France is what Clinton-Trump only approximated: A genuine neoliberal centrist is fending off an anti-immigrant populist with real left-wing policy positions. Left-wing voters are expected to hold their noses and vote for Macron, despite little indication their interests are being served.

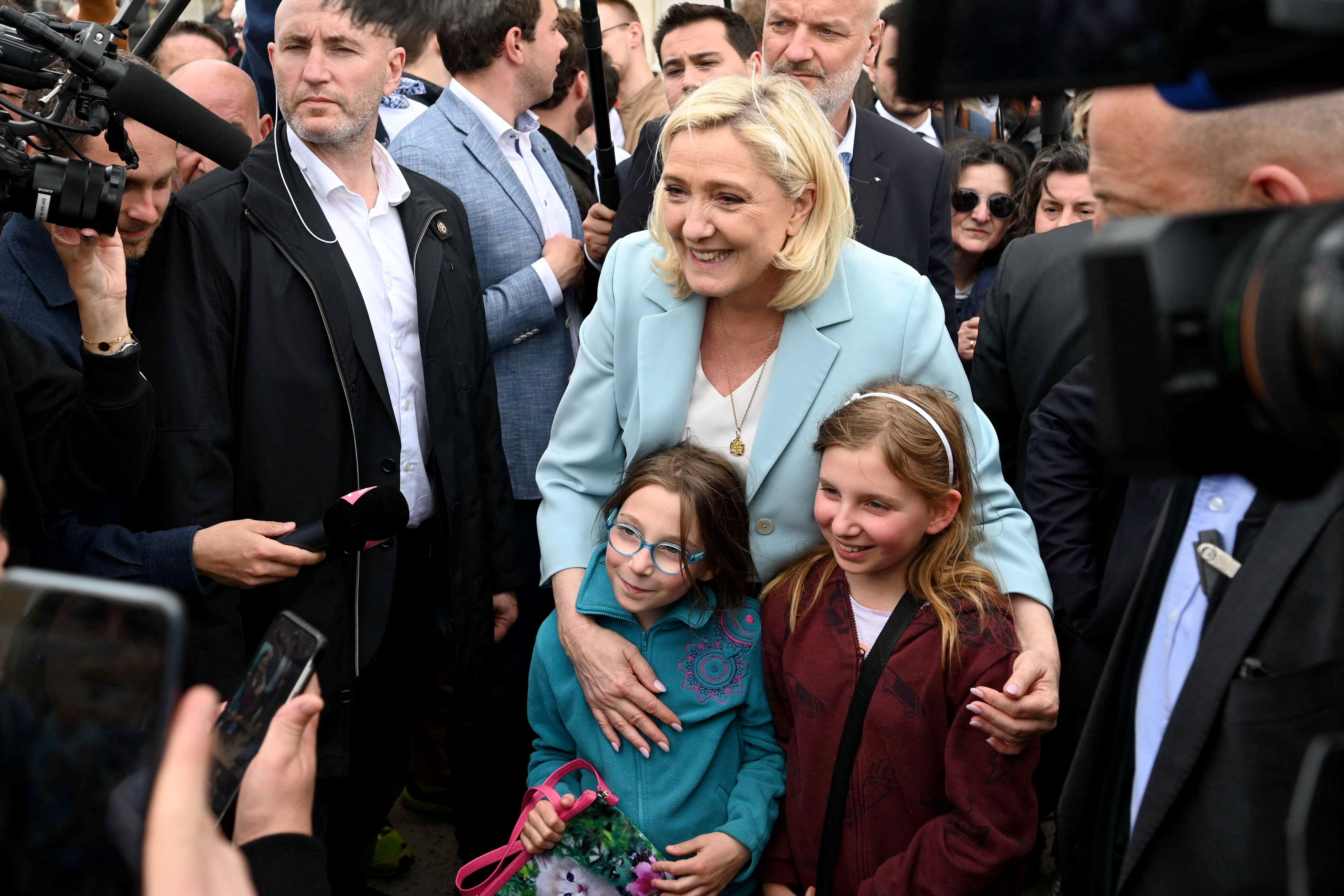

Arras was a good choice for Le Pen’s final pitch. She represents a nearby district in the National Assembly, a seat she pried away from longtime socialist control in 2017. Her economic protectionism has won her National Rally party lots of votes in de-industrialized northern France, where the downward trajectory is impossible to ignore. Arras has a mayor who supports Macron, but Le Pen will likely take a majority in the surrounding countryside. It’s also a funny place to contemplate the role France’s glorious past plays in its future; more tourists come to France than any other country in the world, and they play a huge role in many small-town economies. In Arras, the primary tourist attraction is the nearby trenches, monuments, and cemeteries of the First World War.

The typical attendee at the Le Pen rally was a man in tight jeans and a rugby shirt with gel in his hair. These people were not first-time National Rally voters, and they were not on the fence. Many shared Le Pen’s idea that “massive and anarchic immigration” has so transformed the country they sometimes don’t feel at home. (Well my neighborhood is different, they say, but you hear about some parts of Lille, or Paris…) One young woman told me she had been passed up for social housing because, she was told, migrants got priority. “That was disgusting,” she said.

One difference between Trump and Le Pen? Le Pen’s supporters are not old. According to Ipsos polling, she was the most popular candidate in the first round for French voters between 35 and 60. (French retirees, by contrast, overwhelmingly support Macron.) At the expo center on the outskirts of Arras, I saw young mothers with strollers, couples holding hands, bands of teenagers out on spring vacation. This dynamic bodes well for Macron on Sunday, since older people are the most reliable voters. But it also means that even if she loses, Marine Le Pen’s movement isn’t going anywhere.

At the end of her speech, she got back to basics: “People of France! Stand up against those who have so little consideration for the defense of our civilization, who have denigrated your history, your culture, and your traditions, who have made migratory subversion our demographic horizon.” That’s an allusion to the “Great Replacement” theory, the idea that uncontrolled immigration to France is extinguishing the white race. The campaign may be nice, but the message is as ugly as ever.