For some, the choice of mystical and unconventional subjects expresses freedom, but also the bizarre. For others, long hair and a profusion of tattoos, elevated by a nonchalant and serene presence, make a perfect female incarnation. Both will agree on the fact that Kiki Smith (NA 2006) is a Wild Woman.

The archetype of the Wild Woman has been developed by the poet, writer, and Jungian psychoanalyst Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, who articulated a new vocabulary to describe the female psyche in her 1992 book, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. According to her, the Wild Woman embodies the instinctive nature of women. “From the viewpoint of archetypal psychology as well as in ancient traditions, she is the female soul [in which] a powerful force, filled with good instincts, passionate creativity, and ageless knowing is living.”1

In her more than 40-year-long career, Kiki Smith has always placed women at the heart of her prolific practice. Similarly to the writer, she uses myths and esoteric representations to epitomize the female body and soul. La Monnaie de Paris, the Paris Mint, recently dedicated a retrospective to the artist—her first in a French institution. This exhibition was important both for the artist and the institution because the museum has since shut down its contemporary art program. Thus, the choice of Kiki Smith, an American female and multidisciplinary artist, can be seen as a final independent and engaged reverence by Camille Morineau, the former artistic director. Morineau promoted women artists throughout her time at Monnaie de Paris, with exhibitions such as Women House, a group exhibition of women artists—including Louise Bourgeois (ANA 1990; NA 1994) and Cindy Sherman (NA 2012)—that built upon the landmark Womanhouse, created in 1972 by Miriam Schapiro (NA 1999) and Judy Chicago.

In the majestic staircase of the Monnaie de Paris’s palace, an impressive, silvery, forged bird floated under the Renaissance-style decorated ceiling. Sun, Moon, Stars and Cloud, 2011, a hybrid mobile midway between nature and cosmogonic themes, gave us a preview of the exhibition’s aesthetic and sensory experience. As I continued to visit Kiki Smith again and again during the four months it was showing, I couldn’t help thinking of Clarissa Pinkola Estés’s book. Kiki Smith’s choice of representing wild animals, various type of bodies, or even witches—like Pyre Woman Kneeling, 2002, a dramatic sculpture of a bronze female perched atop a wood pile—resounds to me like odes to the female soul and the Wild Woman archetype, as described in Women Who Run with the Wolves.

The notion of archetype as developed by Carl Jung, the father of analytical psychology, refers to the unconscious mind that manifests itself through dreams, stories, or myths, taking the form of symbols that represent aspects of the personality. Jung’s work is based on psychiatry, philosophy, anthropology, religious studies, and literature, and finds psychological transmitters which transcend eras, cultures, and civilizations. Adopting this approach, Clarissa Pinkola Estés uses either common legends—such as Bluebeard or Baba Yaga—or stories drawn from her travels and inherited Mestiza culture—like Manawee, the Skeleton Woman, or La Loba—to characterize the Wild Woman archetype. Likewise, Kiki Smith uses cosmological stories, myths of creation, and biblical legends to place women in the center of her artistic iconography, often after these figures have been pushed into the background by society, in an act that restores their crucial role in history.

Concomitantly to the Parisian venue, Modern Art Oxford exhibited Kiki Smith: I am a Wanderer. The choice of the title perfectly reflects the Jungian, esoteric dimension of Smith’s work. Thus, considered as a key for reading, the guidance brought to us by Pinkola Estés helps to further understand Smith’s artistic and narrative performance.

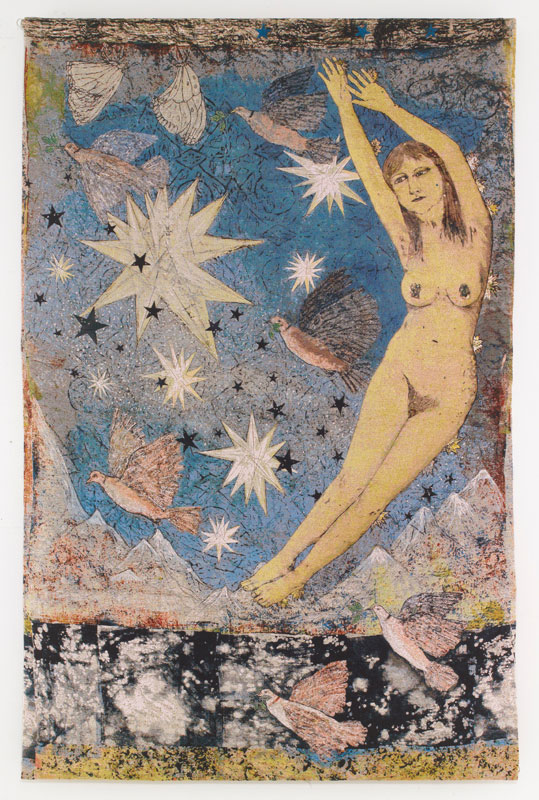

Kiki Smith stands as a feminist. She claims to be profoundly influenced by the movement’s effervescence in the 1970s, when she started her career. At the same time, the conventional female characters of the Occidental tradition, such as the Virgin Mary or Venus, fascinate her. This interest might come from childhood memories, passed down from her Catholic education as well as through fairy tales by Charles Perrault or the Brothers Grimm found in her father’s library.

One of the great figures that frequently crops up in Smith’s work is Geneviève—a Roman Catholic and Eastern tradition Saint who diverted Attila’s Huns away from Paris, and has consequently been considered the patroness of the city. Smith started making drawings and cartoons of her—the Monnaie de Paris exhibition included Sainte Geneviève, 1999, and Lying with the Wolf, 2001—and, later on, sculptures. Among more than 90 works displayed in the historic salons and exterior courtyard, and filling the over 3,000 square feet of the Parisian palace, Rapture, 2001, an impressive life-size bronze carving of a nude woman walking out of a wolf, was presented as the resurrection of the saint. Here, you can sense the influence of Art Deco, as Smith has repeatedly referred to the sculptural work of Paul Manship (ANA 1914; NA 1916).

Some see in Rapture a reference to Little Red Riding-Hood, but in light of the Wild Woman’s appetence to rouse her innate instinctual Self from its passive condition, I consider the Woman and the Wolf here as not two different protagonists, but the same one. Pinkola Estés’s story La Loba illustrates the psychic characteristics shared by women and wolves, such as instincts, creativity, and awareness. With Rapture, the Woman is thus the doppelgänger of the Wolf, reclaiming her wildness and her consciousness.

The texture of the human body is another recurring theme in Kiki Smith’s work. Not to be outdone, the Monnaie de Paris presented a great sampling: various malleable, shaky, fragmented, or distorted works, created in different shapes and with a great variety of media. The exhibition showed Smith at the intersection of standardly accepted canons and what extends beyond our social constructions. In a recent interview with the French radio station France Culture, Smith said: “the history of the world lies in the body—anatomical body, sexual body, political body.”2 Her intention is to both shock and seduce. An exhibition wall showcased the quote: “I think I chose the body as a subject [of my work], not consciously, but because it is the one form we all share; it’s something we all have our own authentic experience of.”

Her interest began as early as 1979, by copying illustrations from an anatomical treatise from the 19th century. Just like the diverse morphologies represented, Smith uses an extensive sample of materials to create her replicas. Bronze, glass, wax, plaster, porcelain, silver, aluminum, copper, photographs, cheesecloth, polymer, Nepalese paper, cast Schott crystal, methylcellulose, tapestry, Japanese leaf, etching, aquatint, cyanotype, Losiny Prague paper, graphite, silver nitrate, video, horsehair, iron, sound installation, wood, drawing, and papier-mâché were all found in the Monnaie de Paris exhibition. To master the use of every material, Smith seeks the best technical expertise and works with artisans.

“Catholicism is a body-fetishized religion,” Smith states in an interview with Michael Kimmelman for the New York Times Magazine. “It’s always taking inanimate things and giving meaning to them. Also my father was ill for the last twenty years of his life. So I thought about the body a lot.”3 Her father, Tony Smith, was a Minimalist sculpture pioneer. In their young days, Kiki Smith and her sister served as studio assistants. Their mother was Jane Lawrence Smith, an opera singer and Broadway actress.

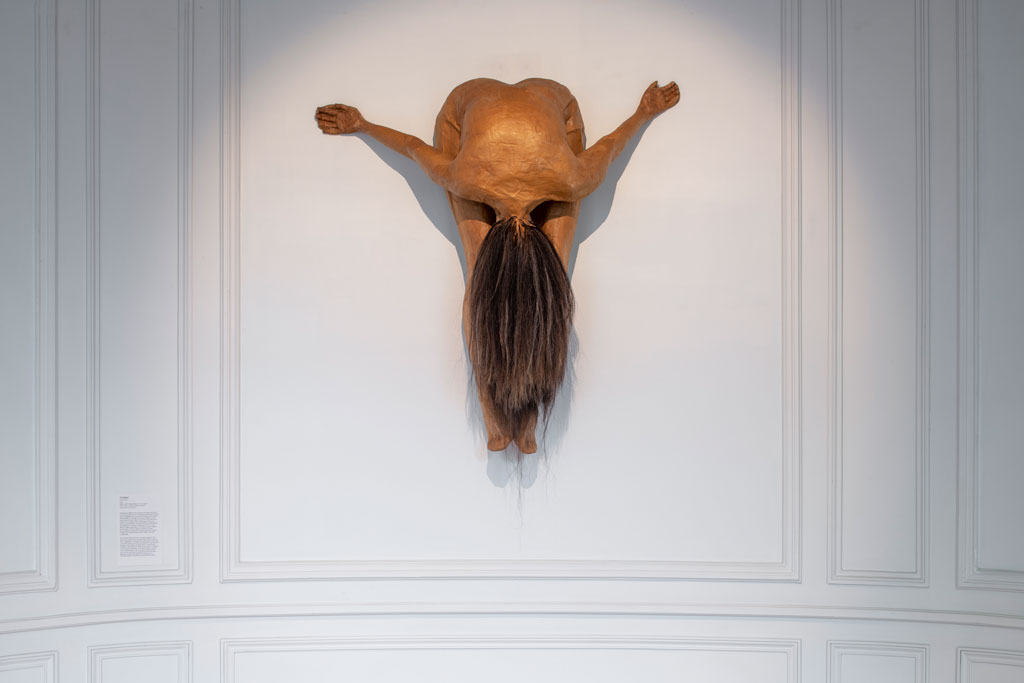

In the Parisian show, a hybrid of a Christ, Untitled III (Upside-Down Body with Beads), 1993, hangs from the wall. In a quotation next to the work, she recalls seeing a small crucifixion statuette of the fallen Jesus in a house in New Mexico where she was working several years ago. With the head upside down, in the style of a Paris gargoyle, this outlandish figure intrigues as much as it scares. The work belongs to a series of visceral sculptures created by Smith in the 1990s. To conceive the sculpture, she cast her neighbor’s lower body, to which she associated the upper part of hers. Not only because major societal issues such as religion and gender cross each other in a subtle and secretive way, but also due to its self-sufficient presence, our breath is taken away when in contact with Untitled III. Clarissa Pinkola Estés notes in her book that over time old pagan symbols were overlaid with Christian ones; by giving her reinterpretation of this biblical figure, Smith builds within this heritage.

Kiki Smith affirms there’s no meaning transmitted through her artworks, but the panel of references in which she inscribes them undoubtedly invites us to celebrate freedom of women and spirits, and human bodies and their symbiotic relations to animals, life, and death. While using a repertoire of resources, she breaks free from common standards around them in a personal and visionary way to honor women’s bodies and souls. Add to this a genuine technical savoir-faire, and a lyrical and aesthetically powerful approach, and we find ourselves immersed in the story she’s telling us.

Kiki Smith was presented at La Monnaie de Paris October 18, 2019 – February 9, 2020.

Léa Miranda is a graduate student in law and the history of art at La Sorbonne (Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne). Focusing on the intersections between the two disciplines, her research offers a new approach to the study of cultural heritage and contemporary art trends.

She has professional experience in museum administration (MAC VAL, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris), and curatorial affairs (National Academy of Design), as well as a six-month placement as an intern in the Photographs Department at Christie’s Paris. She is currently interning in the exhibition production department at Les Rencontres d’Arles, the first international festival of photography, for the 51st edition.

- Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype, Ballatine Books, New York, 1992, p. 16.

- “Kiki Smith, la femme-louve,” La Grande Table Culture, France Culture, October 18, 2019

- “The Intuitionist,” Michael Kimmelman, New York Times Magazine, November 5, 2006