How The Vanderbilts Blew Their Fortune And Went From American Royalty To Flat-Out Broke

- Photo: Jose Maria Mora / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

In Order To Keep Up Appearances, The Vanderbilts Spent Money As Fast As They Made It

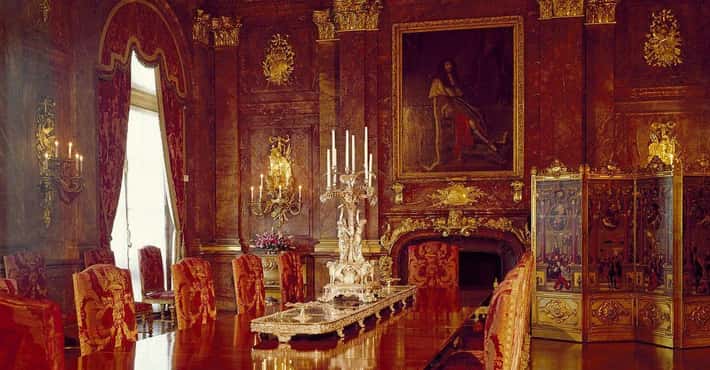

As the Vanderbilts built homes in New York, Rhode Island, and other locations in the United States, they filled those structures with expensive works of art. William Henry had a large art collection, and his children continued his cultural interests. That said, they also spent a lot of money on yachts and cars and held lavish parties.

The Vanderbilt Ball, hosted by William Kissam Vanderbilt's wife Alva in 1883, was intended to boost the Vanderbilt family's position in New York society. The Vanderbilts weren't among the top 400 people in high fashion New York society, as determined by Caroline Schermerhorn Astor and Ward McAllister. Astor and McAllister deemed the family too nouveau riche.

Alva decided to hold a costume party and invite 1,000 people in an attempt to cement the Vanderbilt family name into the upper echelons of society. The event was described by the New York Times as a "fairyland." Guests wore beautifully embellished dresses, spectacular jewels, and fantastic costumes, all hoping to out do one another. The event was full of pageantry, ornamentation, and excess. According to the Museum of the City of New York, "most contemporary sources put the cost of the ball at $250,000 (nearly 6 million dollars in today’s money)."

- Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

By The Mid-20th Century, The Vanderbilts' New York Homes Were All Torn Down Or Sold

During the late 19th and the early years of the 20th century, Fifth Avenue in New York City became a showcase of wealth and luxury. As new families made millions, they acquired and built magnificent mansions. The Vanderbilts owned numerous properties on Fifth Avenue, including Cornelius II's 130-room home. The Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, as it was known, included a small and a large salon, a two-story ballroom, a gallery, and separate dressing rooms, bedrooms, and bathrooms for Cornelius II and his wife. The entire mansion was decorated with imported European decor.

The house was torn down, however, in 1926. New York began changing as real estate developers bought land along Fifth Avenue in a clamor to build skyscrapers. The Vanderbilts were not in a financial position to maintain their land holdings. In addition to the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, William Kissam Vanderbilt's Fifth Avenue home was sold and demolished in 1926.

Vanderbilt Spending Coincided With A Decline In The Family's Economic Success

By the time Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt's grandchildren began inheriting the family's money, the Vanderbilts' economic dominance was declining. By the 1930s, the shipping industry was losing ground to other modes of transportation like cars, barges, and buses. The family sold shares of its railroad holdings, opening the door for competitors to have a majority share in their businesses. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, for example, acquired a large amount of New York Central stock and took over leadership, only to drive the company into bankruptcy during the 1950s and 1960s.

Within thirty years of Commodore's death, no member of the Vanderbilt family was among the wealthiest people in the United States. By 1973, none of the 120 attendees at the Vanderbilt family reunion were millionaires.

- Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Philanthropy Was Part Of Advertising The Vanderbilt Name

Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt wasn't particularly interested in giving his money away, but he did donate $1,000,000 to what would later be known as Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. The Vanderbilts underwrote cultural enterprises such as art galleries and museums, but it was really during the Gilded Age that the Commodore's grandchildren established the family as a great philanthropic entity.

Frederick Vanderbilt's wife, Louise Holmes, was very generous in the Hyde Park area of New York. She helped young girls gain access to education and established a chapter of the Red Cross. The Vanderbilts did everything "from treating school children to an ice cream festival to buying a second hand motion picture machine so the residents of Hyde Park could view movies in the Town Hall." When Frederick Vanderbilt died, he left a significant amount of money to his employees.

William Kissam Vanderbilt gave money to Columbia University, the YMCA, and spent a million dollars on tenement housing in New York. George Washington Vanderbilt II was also a known philanthropist, who paid to design and support libraries as well as arts activities and educational institutions in New York City. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was a trained artist that used her family wealth, and that of her oil-wealthy husband Henry Payne Whitney, to support female artists.

This philanthropic generation was the beginning of the end of the Vanderbilt family fortune.

Anderson Cooper, Gloria Vanderbilt's Son, Has No Access To His Family's Fortune

CNN news anchor Anderson Cooper, son of Gloria Vanderbilt and Wyatt Cooper, has known for some time that he won't be getting any of the family money, and he's okay with it. He told Howard Stern, "My mom's made clear to me that there's no trust fund... [and] I don't believe in inheriting money." He called inherited money an "initiative sucker" and "a curse."

Cooper, who makes millions of dollars a year working for CNN, said he always had a job growing up and, despite his mother's wealth, identifies with his father who grew up poor in Mississippi.

- Photo: Eastman Johnson / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

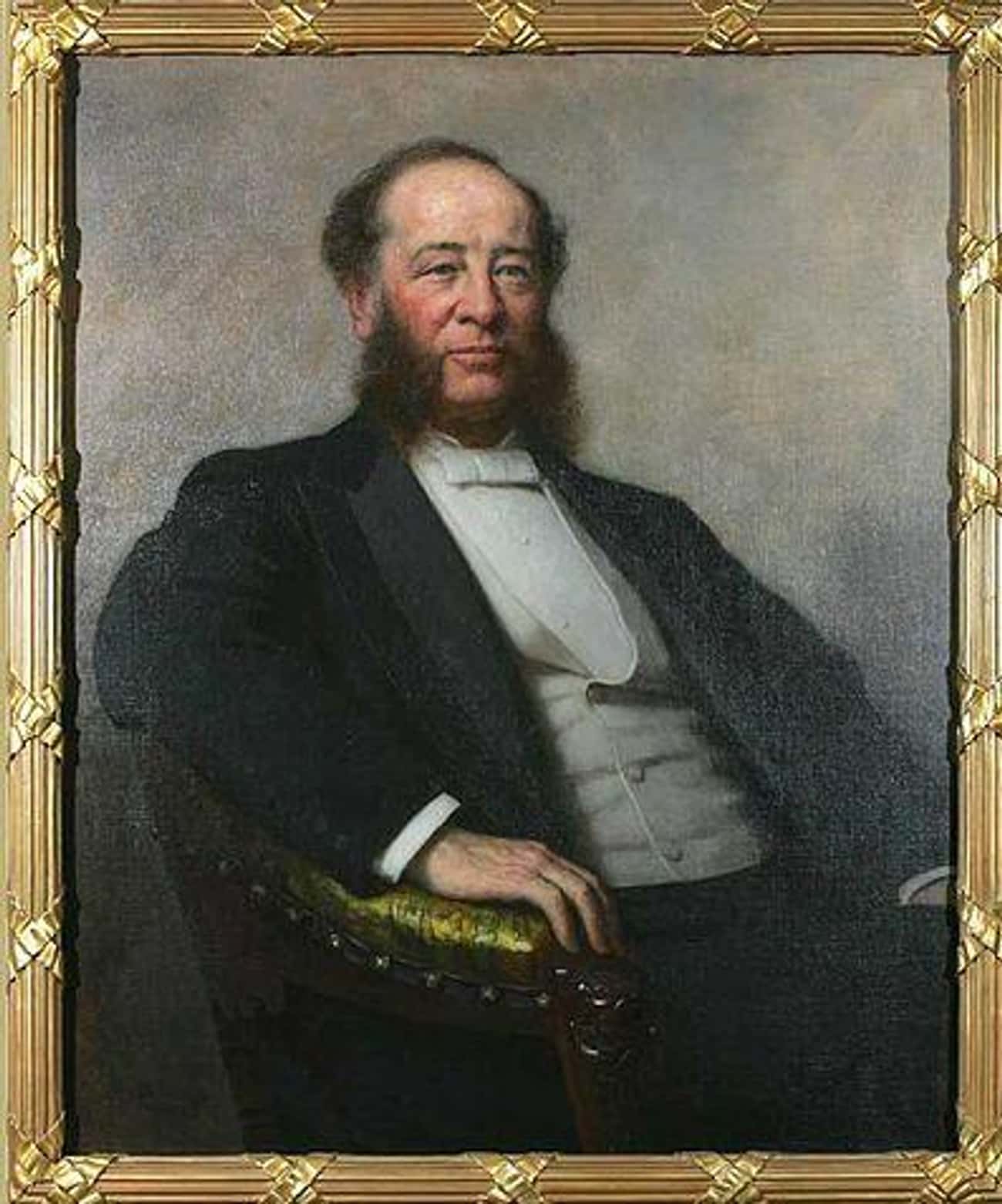

Commodore Vanderbilt Didn't Think His Sons Were Worthy Of His Money

Commodore Vanderbilt married his first cousin Sophia Johnson in 1813. The couple had 13 children together, 11 of which survived to adulthood. The Vanderbilts had three sons, although one boy, George, died in 1864. At the time of his death, the two living boys, William and Cornelius, did little to inspire their father. He often called William a "blatherskite," or a fool, and had Cornelius committed to an asylum on two occasions. The Commodore opted to leave William the bulk of his money, but not before telling him "any fool can make a fortune; it takes a man of brains to hold onto it."

William Henry Vanderbilt suffered a mental breakdown at a young age after working with one of his father's business rivals. After that, he spent most of his time at the family farm in Staten Island where he was successful in boosting its profits. Slowly, William was given more opportunities to work within the Commodore's railroad empire and took it over after his father died.

- Photo: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

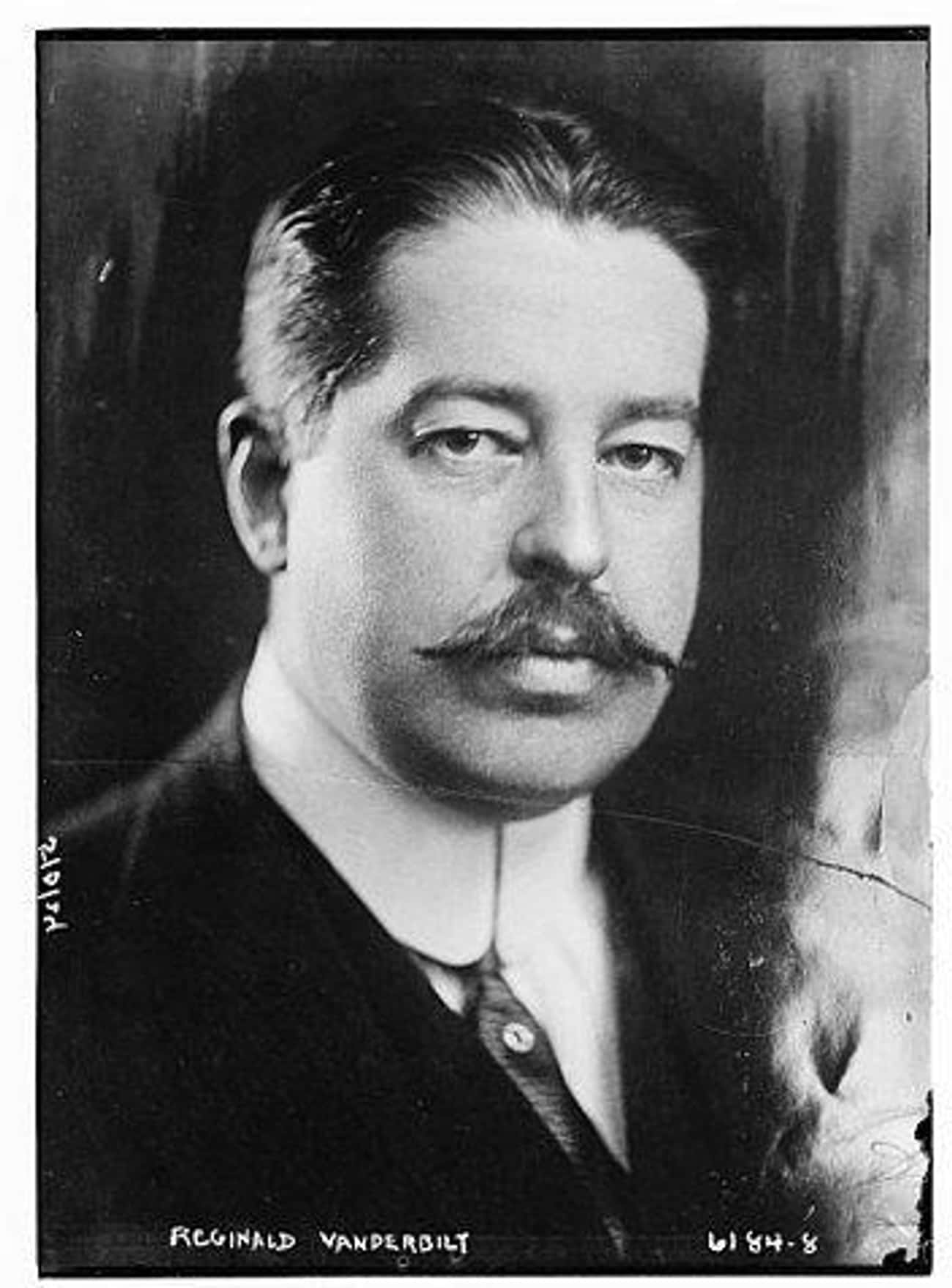

Reginald And His Brother, Neily, Were The First Vanderbilts Who Didn't Increase The Family Fortune

Cornelius Vanderbilt II's youngest son, Reginald, inherited a small sum from his father, but the bulk of the family money went to his older brother, Alfred. The eldest son, Cornelius III, or Neily, spent large amounts of money before falling out with his family and once commented that "every Vanderbilt son... has increased his fortune except me."

Reginald was a playboy who gambled and drank often. On the night Reginald turned 21 years old, "he celebrated coming into his $15.5 million inheritance by losing $70,000 at the gambling table." He later died of cirrhosis of the liver due to his alcoholism. Reginald had little ambition and didn't make any money for his family, preferring to spend it instead.

In 1922, Reginald married 17-year-old Gloria Morgan. She gave birth to their daughter, also named Gloria, in 1924. Reginald died the following year broke and in debt, leaving his wife and child with only the interest from his daughter's future trust fund.

- Photo: Unattributed / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

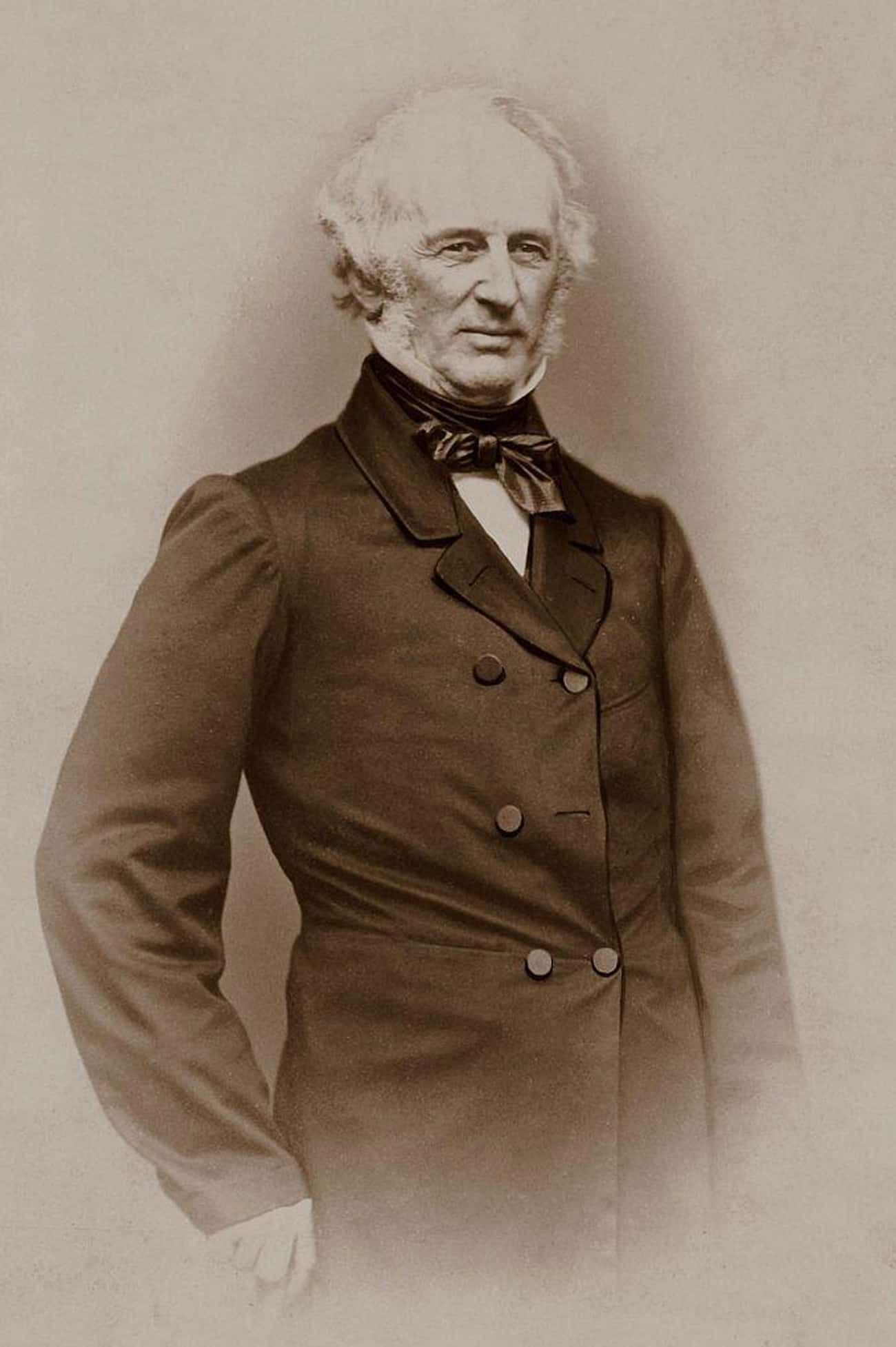

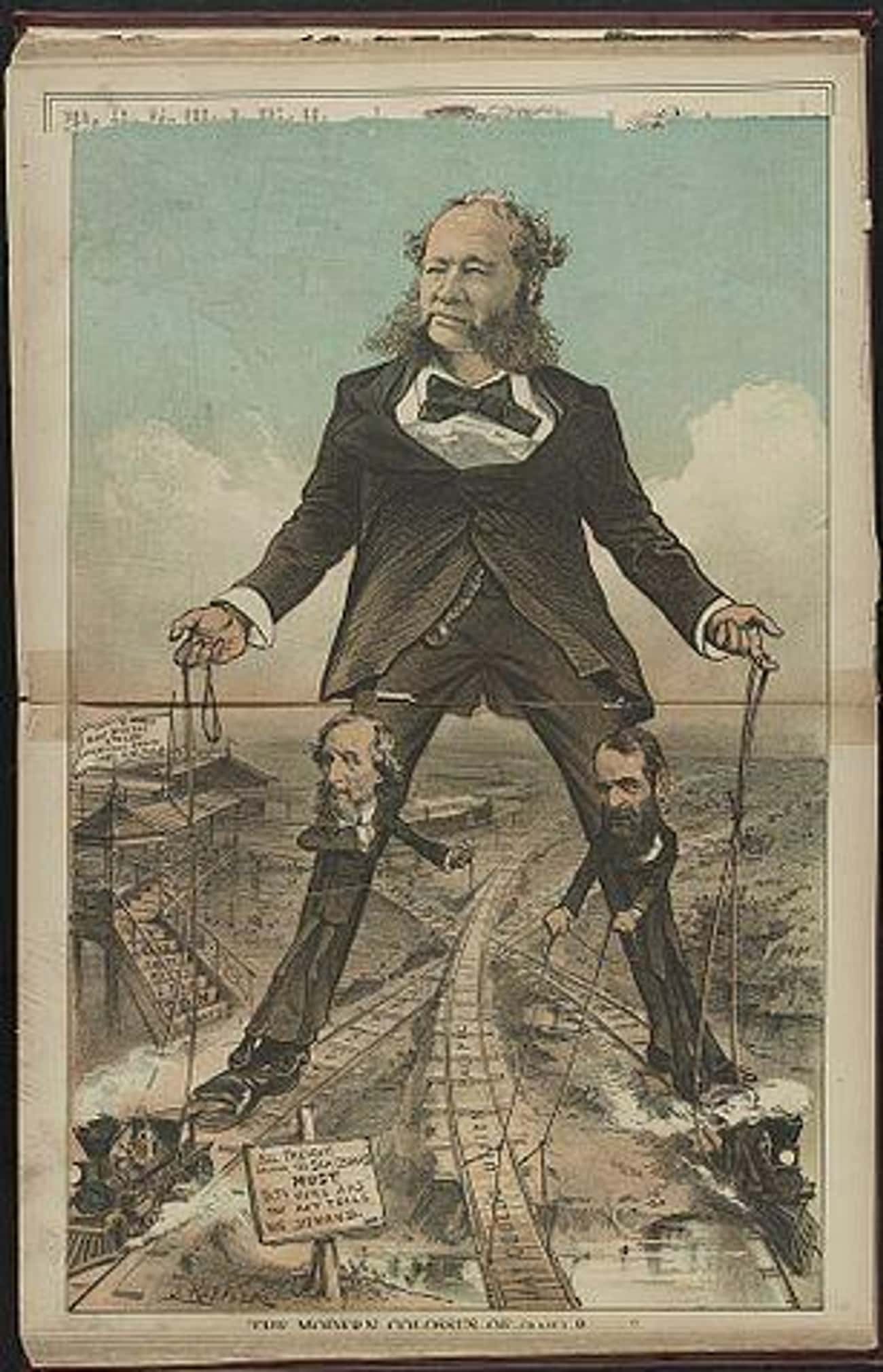

Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt Started Building The Family Fortune From A $100 Loan

The Vanderbilts, native to the Netherlands, got their start in the United States sometime during the late 17th century. The Dutch immigrants were farmers and lived in relative obscurity until Commodore Vanderbilt came onto the scene in the early 19th century.

Commodore Vanderbilt was born in 1794, and at the age of 16, he borrowed $100—around $2,000 today—from his parents to purchase a flat-bottomed sailing barge called a periauger. Vanderbilt was working with his father, ferrying goods back and forth from Staten Island to Manhattan, but he decided to branch out on his own. He agreed to share the profits with his parents and began transporting cargo in the New York harbor, out-advertising and undercutting the competition. The shrewd businessman made about $1,000—approximately $21,000 today—in his first year and soon had several ships, then eventually a small fleet at his disposal.

- Photo: James Bard / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Commodore Vanderbilt Played A Key Role In Establishing Federal Regulations Over Interstate Commerce

Commodore Vanderbilt put his $100 investment to work and grew his shipping business quickly. Within two years, he'd contracted with the US government to supply outposts during the War of 1812. He added ships to his fleet, learned about ship design and open-water sailing, and by the end of the War had earned $10,000 in revenue from transporting people and goods from Boston to Delaware Bay.

In 1817, Vanderbilt began working with Thomas Gibbons to ferry individuals between New York and New Jersey on steamships. Owned by Gibbons and run by Vanderbilt, their Union Line technically violated the state monopoly over shipping held by Robert Fulton, Robert Livingston, and Aaron Ogden. In the case Gibbons v. Ogden that went before the US Supreme Court in 1824, interstate commerce was ruled subject to federal regulations, allowing the Union Line to continue business without issue. By 1827, Union Line was making more than $40,000 a year, which is approximately $924,000 today.

William Vanderbilt Doubled The Family's Money

William Henry Vanderbilt, born in 1821, carried on his father's business legacy, expanding railroad operations in New York to cities like Chicago, Cleveland, and Indianapolis. Between 1877, when his father died, and William Henry's own death in 1885, the Vanderbilt 's fortune increased from $100 million—more than that of the U.S. Treasury—to over $200 million because of William Henry's business efforts.

When William Henry died, the Vanderbilt money was divided among his eight children—four girls and four boys. The family stake in the company was left to the two oldest boys, Cornelius Vanderbilt II and William Kissam Vanderbilt, who ran the enterprise after their father retired in 1883.

- Photo: Bain News Service / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

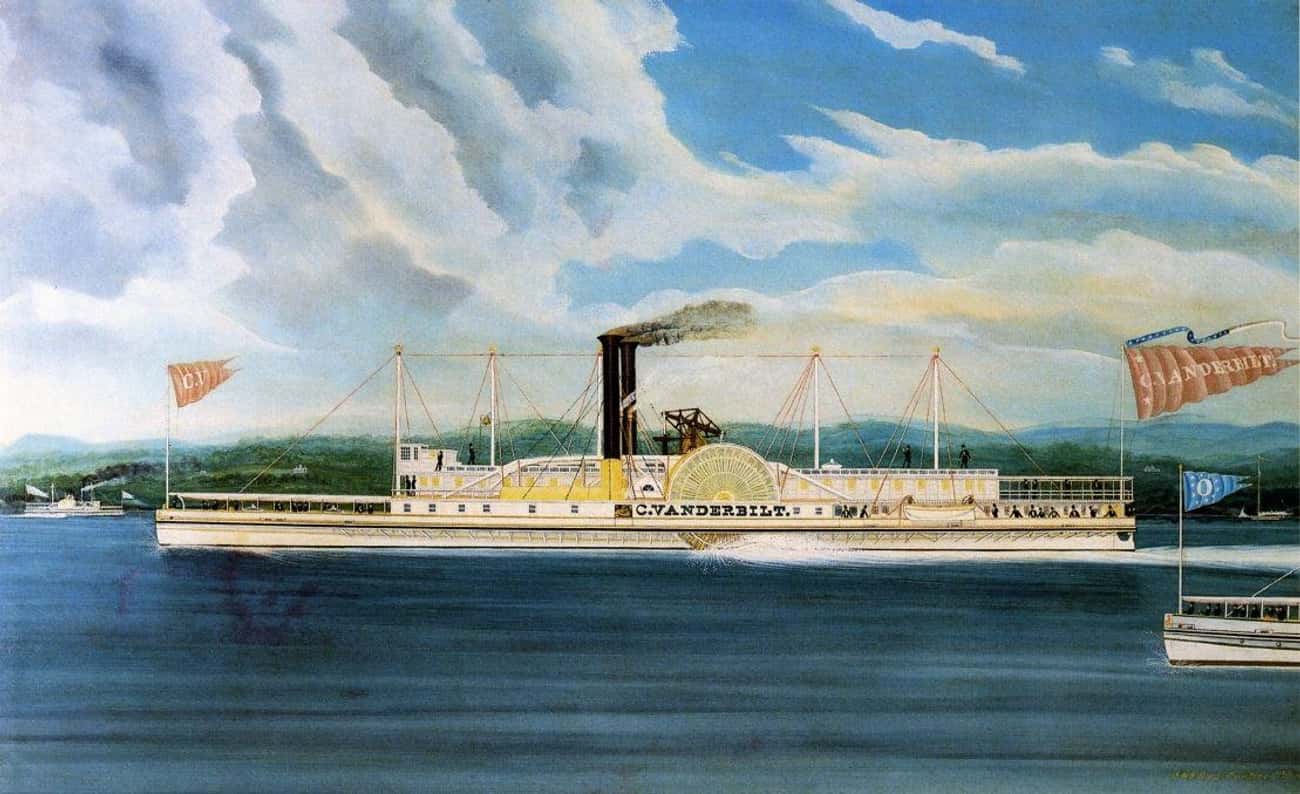

The Vanderbilts Built Luxurious Homes Throughout The United States

After William Henry Vanderbilt died in 1885, his fortune was split among his children. Cornelius II received $80 million, William Kissam got $60 million, and the two younger boys got $10 million each. The brothers spent their money well. Cornelius II bought The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1885 and turned the small house into a villa during the 1890s. He employed architect Richard Morris Hunt who brought in a team of international craftsmen to "create a 70 room Italian Renaissance-style palazzo inspired by the 16th century palaces of Genoa and Turin."

Hunt was also responsible for George Washington Vanderbilt II's home near Asheville, North Carolina, the Biltmore, and William Kissam's New York City mansion on Fifth Avenue, known as "Petit Chateau." The Petit Chateau was modeled on Parisian homes and was the pinnacle of Gilded Age architecture. The Vanderbilts owned numerous properties on Fifth Avenue, including the "Triple Palaces," three townhouses built in 1882. They also owned Cornelius II's townhouse, the largest home ever to have existed on the island of Manhattan.

Frederick William, who only received $10 million, invested his money into coal, tobacco, oil, and steel, out earning his older brothers exponentially. He was worth $78 million by the time of his death in 1938. He, too, had a home in Newport, called Rough Point, and lived at Hyde Park in New York.

Gloria Vanderbilt Made Her Own Money In The Fashion Industry

Gloria Vanderbilt never really knew her father, and her mother was borderline neglectful. Gloria stayed with a nurse for most of her life. Gloria's aunt, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, offered to let the child recuperate with her. Gertrude enrolled Gloria in school and cared for her while her mother was gone for months at a time. Eventually, Gloria's mother returned and filed for official guardianship of her daughter, fearing her sister-in-law was trying to push her out of the child's life. Gertrude refused to hand the child over, claiming her mother was unfit.

The issue went to trial in the 1930s, and Gloria ended up living with her aunt during the school year and spending her summers with her mother. As a teenager, Gloria became a socialite who went to Hollywood for a time before moving back to New York to study art and acting. She started designing jeans during the 1970s and later branched out to other kinds of fashion. She became financially successful in her own right, building on her family's fortune.

- Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Commodore Vanderbilt Couldn't Buy Out His Partner So He Financially Strangled Him Into Submission

Commodore Vanderbilt was unsuccessful in his attempt to buy Thomas Gibbons's son out of their business. As a result, Vanderbilt started his own steamship enterprise, the Dispatch Line, and slowly drove the Union Line out of business. In 1830, the Union Line was forced to sell to Vanderbilt. This pattern continued along the East Coast as Vanderbilt bought out competitors or simply forced them to shut down. By the late 1850s, Vanderbilt expanded his shipping routes, extending his reach across the Atlantic.

Vanderbilt also started investing in railroads, especially as economic opportunities presented themselves on the West Coast. Just like he had done with shipping, Vanderbilt gained control of numerous small railroad companies, combining them under his control. He soon controlled railroad travel in and out of New York City as well, creating a monopoly of his own.

His efforts not only resulted in massive wealth but also helped standardize railroad procedures, timetables, and overall efficiency.

As a ruthless businessman, Vanderbilt was a millionaire by the age of 50. Known for his "toughness and use of profanity," the Commodore—a nickname he got early in his career—didn't indulge in excess and wasn't a great philanthropist. His descendants inherited his $105 million when he died in 1877.