Sixteen enormous tree stumps, their roots turned towards the sky, stand in a circle in a country park. The mist and deer gather around. This magical-looking sculpture is placed where the Norfolk hamlet of Houghton once stood, until Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister, moved the vista-spoiling villagers further from his lavish new Palladian mansion.

Houghton Hall is a venerable stately home these days, but White Deer Circle, as this work is called, is new – created by Richard Long for an exhibition that, unusually for this visionary land artist, is being held outdoors. His stump circle is an uncanny echo of a Seahenge, an ancient wooden circle discovered on a beach 12 miles away. Amazingly, Long, who this year marks 50 years of showing his walking-inspired work, has never heard of the bronze age relic. Perhaps Long is listening to the landscape more closely than most, though, for he is unsurprised by such serendipity.

“All these coincidences are part of the natural way of things, aren’t they?” says the artist, whose minimal, modernist landscape works first disrupted pop art in 1967, when he was still a student at St Martin’s in London. He took a train from Waterloo, found an ordinary country field and walked up and down it, then took a photograph of his traces and exhibited it under the title A Line Made by Walking.

“When I made my straight line, I didn’t know about the other straight lines – the famous Nazca Lines in Peru, or Alfred Watkins, who wrote The Old Straight Track.” It was Watkins who coined the term ley lines. “We as humans come to the same visual coincidences through different cultures and eras and histories. That’s all interesting.”

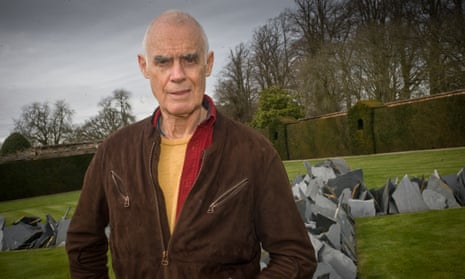

We meet in a grand room at Houghton Hall, where Long is putting the finishing touches to his show, Earth Sky. Despite trekking to the four corners of the globe, recording his journeys and the traces he leaves behind, he’s found the time to put on 70 exhibitions this century alone.

Does he do more than he should? “Probably.” What’s driving him? “I would like to do fewer shows but more work. I’d like to do more walks. That’s my real love. So I get a bit frustrated if too much of my time is taken up with admin. But I’m not complaining. I’ve had a very lucky life. In some ways, I’ve had a very poetic life – in charge of my own destiny, doing what I want, and being paid for it, and people appreciating it.”

Long is feted for his heroic treks as well as the ideas that spring from them. Tall and lean, he’s now 71 and keeps fit by cycling. He can still walk 30 miles in a day, tent on back, camping wild. “Often the ideas come after I’ve started a walk,” he says. “I once set out to walk across France from the mouth of the Loire to the Swiss border. It started out completely cloudless and, day after day, was cloudless – and then I thought it was a much better idea to finish the walk when I saw the first cloud. So sometimes circumstances can present a better idea. I like being open to that kind of serendipity and chance. That’s at the heart of my work really.”

As a young artist, Long was determined to make his mark. When he sold his first show, he spent the £250 raised on climbing Kilimanjaro, on which he erected a kind of prayer flag. He wrote to the Guardian, but never heard back. “I was very proud of the fact I had probably made the highest sculpture in the world.” Was that a young man seeking a challenge? “It was a young man trying to make a work of art that hadn’t been done before.”

Since then, his work – from photographing the outline made by his sleeping body in the rain to more enduring circles or lines in stone – has shunned the monumental, though it is not completely ephemeral either. “I’m not interested in making monuments, but the other point of view is to leave absolutely no mark – take only photographs and leave only footprints. There’s quite interesting territory between those two positions – like moving stones around, making works which disappear, or making water marks – many ways of being artists in a landscape.”

I wonder if he considers his legacy at this stage in his career. “I happen to know that my circle near the Burren in Ireland is still more or less as it was when I made it in 1975, but that’s not to say I want people to know where it is. It’s never my intention to make a famous site for people to visit. My work is much more about the spirit of making marks of passage.”

Besides, a good idea endures. “Ideas can last for ever,” he says. “I’m one of the artists who realised a journey – from a straight path in the grass to a 1,000-mile walk – could be a work of art.” But he does not seek to influence others. “I have no desire to leave my mark in that way because what I do is only what interests me. I followed my nature and instincts and desires when I was a young artist – and I think young artists should do the same.”

While an outdoor exhibition is not quite new for Long, it is a departure from his more familiar terrain and materials: it has not begun with a walk, and nor is he using his favourite River Avon mud. There’s some Cornish slate (which he loves) but it’s mixed with Norfolk flint, while another piece is made from gorgeous local ginger-coloured carrstone. Then there are his “mud paintings” in a kind of limewash, reflecting the chalkiness of this landscape.

Despite being so well-travelled, Long has based himself in Bristol his whole life. Does he find flatter, drier and bleaker East Anglia rather alien? “Alien is a bit strong. Bigger skies, colder wind – it’s another type of English landscape and I’m moved by it, of course I am, but Dartmoor and the Somerset Levels, the Quantocks, the Cotswolds – that’s my heart landscape.”

He’s walked every piece of Dartmoor, but avoids pilgrim routes and old ways. “I made a conscious decision that there’s so many ways to walk in new ways or original ways. I was quite proud of the fact that no one has walked across Dartmoor in a straight line before.”

Long’s work appears highly pertinent in an era of ecological crisis, but it isn’t overtly political. “Green politics wasn’t really invented when I started. My work comes out of wanting to make art in new ways. The world outside the studio represented a fantastically colossal opportunity to engage with the physical world. It was my interest in making new art that took me into the landscape. I’m not a political animal. I’m an artist animal. But obviously my work does celebrate nature and the wonderful landscapes that cover most of the planet.”

Long really comes alive when we step outside, walking briskly over to his new creations. “It’s a bit incredible really, isn’t it, to get away with it?” he laughs as we look upon his Cornish slate exploding out of Houghton Hall’s croquet lawn. He placed all the slates himself. “I don’t have a factory where people fabricate it for me. That’s not a value judgment, it’s just my preference. One reason to be an artist is the pleasure of making.”

Similarly, walking gives him enormous pleasure. Outside, in the open air, he seems to uncoil his tall frame – and any tension. Does he ever struggle on a walk? He talks about getting stranded in the snow. What about mentally? “No, most of the mental hard times in my life have been in domestic [situations] or cities. I have a sense of wellbeing by being out in the wilderness. It’s a kind of therapy. It’s healing.”

Earth Sky: Richard Long is at Houghton Hall, Norfolk, 30 April to 26 October.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion