Among the Panama Papers – 11.5m documents that comprised the biggest data leak in history – were details of enough privately collected Monets, Picassos and Hirsts to fill a museum. But these were not the Panama Paintings exhibited at Neu West Berlin last week. Instead, the gallery has been showcasing what London-based German artist Philipp Ackermann calls his “offshore paintings”.

If it wasn’t for the media frenzy surrounding the Panama Papers, the show would never have come about. It all started when Neu West Berlin’s curator, Matthias Crause, invited Ackermann to exhibit at short notice. With less than two months to put together a show, Ackermann employed a time-saving concept he had used before. He asked the curator to play artist’s assistant and paint a copy of one of his paintings to show in the exhibition.

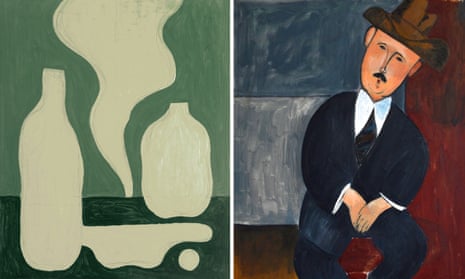

But Crause didn’t paint a thing. Instead, he asked Galician painter Daniel de Isabel to make the copies. Crause calls the concept “painting with an invisible hand” – Ackermann gave De Isabel instructions on how to make the works via phone and email, directing the exhibition from his London studio to ape the degrees of remove involved in the offshore dealings exposed by the Panama leak.

The concept is based on political philosopher Robert Nozick’s theory of the “invisible hand” or in Ackermann’s words “orders that give the impression they’ve been created by a central authority”. The only thing the artist is evading here is paintbrush-to-canvas elbow grease and maybe some shipping costs. Still, the aim was to make the paintings look like what Crause calls “an offshore, undercover business”.

It’s not a new idea in art either – a parallel can be drawn to Lieber Maler male mir (“Dear painter, paint for me”), in which German artist Martin Kippenberger contracted colleagues to paint works on his behalf. “He used a multitude of strategies to obtain the highest possible profit from his ideas, though not necessarily financially,” says Ackermann of the earlier project.

As for De Isabel’s copies, the samples were “very convincing” and Ackermann believes he picked the “right person for this job”. The exhibition’s title is knowingly promotional. “The hype which the media has created around [the leak] seems like a piece of art to me,” says Ackermann. “The Panama Papers name is an accomplishment in itself.”

Among the artworks on show is an abstracted interpretation of Seated Man With a Cane, a 1918 painting by Amedeo Modigliani, which is worth £18m and was the subject of a legal dispute between a New York art gallery and the heir of an art dealer who fled the Nazi regime during the second world war. Ackermann made the abstract version of the Modigliani and painted a version of it in oils, from memory, before De Isabel reproduced it. Visitors walking in wouldn’t know the Ackermann from the De Isabel. The gallery becomes a shell company of sorts for shady dealings.

“When you’re contracting someone else to make the paintings, authorship and copyright come into play,” says Crause. “It’s an intervention, not just an exhibition.” The Panama Paintings are not only symbolic of the scandal, but of wider corruption in the art market. “Money laundering in the art world is everywhere, but without the scandals. Where does the money go? Where is the ownership? It’s this behind-the-curtains process with rich people.”

Even in a show that uses the Panama Papers as a starting point, some details remain hidden. Ackermann’s works are valued upwards of £1,600, but where will the money go if they sell? “That’s yet to be decided,” says the artist.