« Features

In the Shadows of Global Consumerism. A Conversation with Ni Haifeng

Part of the mid-1980s New Wave movement in China, which includes the likes of Xu Bing and Wenda Gu, Ni Haifeng is one of the most daring and explicit of that generation to deal with the history of China’s embrace of capitalism. After immigrating to the Netherlands in the mid-1990s, his work shifted away from Nonsense Calligraphy (a hallmark of the New Wave movement), and began focusing on complex historical circulations of people and goods, as well as the issues of authorship, copyright and value that arise from trade history. In Of the Departure and the Arrival (2005), for instance, he played off the material history of Delftware, asking the citizens of Delft to contribute contemporary household objects to be copied in blue-and-white porcelain by a factory in Jingdezhen. These objects were then packed and transported back to Delft and exhibited in a display that included their shipping cartons. This piece opened up multiple avenues of investigation regarding China’s position in the global economy, resulting in one of Ni’s most famous installations, Para-production, which focused on the invisibility of Chinese labor and sheer material weight of global apparel manufacturing. First shown at Joyart Gallery in Beijing in 2008, it has since been included in “The Global Contemporary” (2011), at ZKM Karlsruhe, and “The Deep of the Modern,” Manifesta 9 (2012), in Genk, Belgium. Ni has also recently turned his attention to the consumer economy of art with the projects In Search of a Perfect Equation (2010), Reciprocal Fetishism (2010) and Things Themselves (2013). Moving fluidly from the history of Dutch collections to the contemporary craze of contemporary Chinese art, Ni positions our present fascination for objects within a larger meditation on the desires that drive such economies.

By Jaimey Hamilton Faris

Jaimey Hamilton Faris - You have recently had major success with your installation project Para-Production. I think the strength of this piece lies in the way you directly take on difficult issues regarding the Chinese labor economy. Can you give me a bit of the backstory regarding Para-production? How has the success of this piece led to your current projects?

Ni Haifeng - Para-Production, like much of my work, has an emphasis on the ‘made-in-China’ phenomenon, which is partly an autobiographical response to the fact that I live in Amsterdam. When I entered Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou in the mid-‘80s, there was no contemporary art in China beyond the Stars Group. Our education was in Russian social realism. But we were all autodidacts. Besides the official curriculum, we read a lot of modern Western philosophy and literature, as well as Chinese classical writings. I felt an urgent need to break away from my education.

When I moved to Europe, the very fact of leaving ‘home’ provided me with the possibility of viewing things from different cultural coordinates and of overcoming the narrow definition of ‘Chinese culture.’ Apart from a widened perspective, living in Amsterdam, the capital of the old colonial empire, inspired me to understand the economic relations of the world from an historical perspective. I came to see some perpetual patterns of domination and subordination that still persist in the present era of globalization.

There was a shift in my work around the late 1990s, as I became more and more interested in the phenomenon of globalization and the increased movement of people and things. Ever since, I’ve made pieces that have carried on the recurring themes of economy, production, labor and China-West relations in different ways and with different emphasis. Para-Production was part of this group of works. It actually stems from another piece I did in Amsterdam, The Return of the Shreds (2007).

J.H.F. - In The Return of the Shreds (2007), shown in the Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal in Scheltema, Leiden, you shipped tons of shreds of discarded post-production fabric collected from apparel factories outside of Beijing, right? And then displayed them in one big pile?

N.H. - Yes, I wanted The Return of the Shreds, and later, Para-Production, to focus on the condition in which China becomes the collective working class of global consumerism. The choice of scraps of fabric is the basis of the concept, which is what I call the shadow of global consumerism-the waste material left behind and kept unseen in our euphoric consumerist society. So collecting and shipping of the textile waste material were essential elements of the work. The piece was about the return of the unwanted thing to the symbolic center of consumerism. The Return of the Shreds was located in a dismantled 19th-century textile factory in Europe that is now a contemporary art museum. I specifically chose shreds left over from products destined for Europe. I remember the shipping company was really perplexed by the fact that I would pay so much money to ship a container of such useless material. The container was detained for one week at the Dutch border, simply because customs failed to grasp the purpose of this shipment and needed to investigate. For me, as an artist, it was a rich experience of operating within the mechanisms of economy and commerce and struggling with various authorities that control the flow of things across national borders. My new understanding was that if we regard the movement of the material as an integral part of the artwork, then it is a direct intervention within the mechanisms of the global trade.

J.H. - How did this evolve into Para-Production?

N.H. - I had been looking for a way to recontextualize this concept and material in China. I thought it was relevant to stage an askew rehearsal of production, an activity that was prevalent but invisible in the everyday city life in Beijing. I also decided to produce a ‘useless’ product within the duration of the exhibition. This was where the title Para-Production came into being, which means, to resemble a conventional production process, but in essence quite the obverse. Considering many paradoxical aspects of contemporary Chinese society, specifically the co-existence of capitalism and Marxism, glamorous consumerist metropolises and a nation as the collective proletariat of the global market, and so forth, I decided to introduce a relational element, a participatory process, to Para-Production.

Ni Haifeng. Para-production, 2008. Installation view of textile shreds, sewing machines, work in progress, Manifesta 9, Genk, Belgium, 2012. Courtesy In Situ Fabienne Leclerc, Paris; Limen Travo, Amsterdam.

J.H.F. - How did the participatory aspect work?

N.H. - The walk-in visitors would be confronted by a strange mise-en-scène of a pseudo-factory and a pseudo-product being processed, and read, in an adjoining space, a dusty page from Marx’s Das Kapital on money and commodities, as well as a gigantic wall text of HS codes, which designate numbers to all the objects on the planet that are tradable. It was an open space and a mutating process, in which they could, if they wanted, help to sew the pieces of fabric together. I think the visitors were very diverse, and so were their experiences. Some of the participants, for example, might have seen the connection to the working-class life, some might have enjoyed the co-production of the artwork or a sense of community, others wondered at the monumental scale of the waste material and the indefinable product. I wanted the site to provide the participants/viewers a possibility to transcend, though momentarily, the banal economic world.

J.H.F. - I like that you see the ambiguity and variety of how viewers might participate in your work. It reminds me of Surasi Kusolwong’s work, which also meticulously enacts aspects of our global commodity culture, and often specifically through the lens of the global art biennial world. The major difference that I see between his work and yours is that he focuses on allegorizing global consumption, while you are focused on the production side of the economy.

N.H. - I am not that familiar with his work, but I am quite intrigued by a few pieces I have seen or read about. His Markets, for example, are very intelligent. I like his playfulness and sometimes his deadpan humor. Allegorizing is a very accurate characterization of his work.

J.H.F. - His work, because it essentially operates within the system he wants viewers to witness, often raises ethical questions. Do questions of ethics come up for you?

N.H. - Questions of ethics do concern me a lot, insofar as they are discussed in the full complexity of our time. Especially in the context of postmodern relativism and global capitalism in which art production and consumption become increasingly part of the capitalist culture industry. For an artist, issues of ethical position are difficult but very urgent and intriguing. What I am trying to say is that the absolute right or wrong is hard to imagine, while cynical relativism is often too easy a way out. With Para-Production, I was focused on the social dimension of the economy, of production and consumption, perhaps with an idealistic aspiration to create a political space within the hegemonic system of the global capital.

J.H.F. - How do you feel about showing Para-Production outside the context of Beijing? How does it change the meaning of the piece and the ethical situation of the participants?

N.H. - I view it as resituation and continuation of the ‘para-production.’ In Manifesta 9, for instance, which ran for three months, local and international visitors continued to add to the para-product that originated in Beijing. The visitors were quite aware of the ethical dilemma regarding the relationship between global consumerism and the unseen ‘sweat-shop’ laborers. As the Biennial was held in a decommissioned coal mine, Para-Production was superimposed onto the historical shadow of the early industrial laborers. The installation occupied the huge ballroom where miners used to dance.

Ni Haifeng, Things themselves, 2013. Installation view, oil on canvas, porcelain vases, porcelain plates, wooden chair, bed skirt, bed cover, pillows, woolen coat, bronze fire pokers, Museum van Loon, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Courtesy In Situ Fabienne Leclerc, Paris; Limen Travo, Amsterdam.

J.H.F. - Since Para-Production, how have you enacted other kinds of para-economies or used the logic of commodities to expose the process of abstracted value?

N.H. - I’ve made pieces like Reciprocal Fetishism (2010) to shed some light on the Chinese art world, which is totally dominated by monetary value and symbolic exchange. It’s an extreme version of the commodification of cultural production and consumption. On the other side of the ocean, I am also continuing to explore this question in terms of the meaning of art objects, artifacts and their values in European musicological presentation.

I just finished Things Themselves (2013) for the Museum Van Loon, which invited me as one of 11 artists from the countries with which VOC or the Netherlands had trade or colonial relations, to participate in the international exhibition “Suspended Histories.” The museum is dedicated to the wealthy Amsterdam family Van Loon, which for four centuries remained prominent in Dutch economic and political life. The family was part of the history of the rise of Amsterdam in the Golden Age. The first generation of Van Loons were co-founders of VOC (the Dutch East India Company). My project was to replace some key artworks and artifacts on display with reproductions made by contemporary laborers in China. The reproductions were presented alongside the authentic museum objects. Some of the reproduced objects are truthful copies of the original, some even excel the original in craftsmanship, and some are distorted from the original, intentionally or accidently. The viewing experience sometimes is like a puzzle game of spotting the ‘counterfeits.’ In some way, the counterfeit artworks and artifacts can be seen as empty signs in the otherwise seamless narrative of the museum, which is thus disrupted. In a museological sense, they are devoid of symbolic value and can therefore be seen as just things, more overtly expressing their materiality, the aggregation of labor and traces of life.

Ni Haifeng, Voices of the Proletarian, 2013. Installation view of velvet cloth, factory docks, stainless steel sculptures, HD videos on projection, Gemeente Museum Helmond, Netherlands, 2013. Courtesy In Situ Fabienne Leclerc, Paris; Limen Travo, Amsterdam.

J.H.F. - Marxist critiques of labor and material, especially those by contemporary philosopher Slavoj Žižek, figure strongly in the logic of your work. How do you update concerns about labor relations in a way that makes them understandable to your viewers?

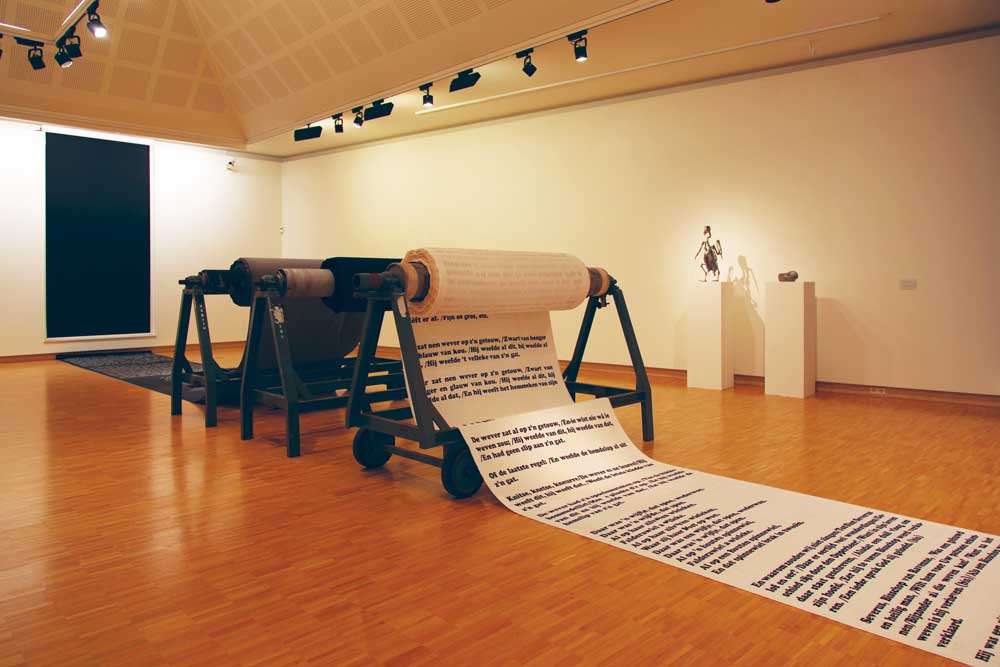

N.H. - Sometimes I work with specific histories and context to foreshadow labor issues. For instance, my new piece Voices of the Proletarian (2013) was developed in the Dutch city of Helmond, part of former industrial area North Brabant. The city was one of the most important textile producers in the Netherlands, but gradually lost its position in the 20th century and hundreds of decommissioned factories. Today there is only one velvet manufacturer that remains-Raymakers. With issues of labor and industrial life in mind, my approach was to focus on the leisure life of the workers. In this context, I regard worker’s leisure as a form of politics in resisting the control and exploitation of early capitalism. I commissioned Raymakers to weave 100-meter-long velvet fabrics with hundreds of weavers’ songs sung for centuries (some as early as the 16th century). Adjacent to the scrolls, I positioned two silver colored stainless-steel sculptures. One is a life-size cast of a deflated football collected from the local football club. The other is an oversized pigeon skeleton. Both football and pigeon-keeping were very popular off-work activities for the industrial laborers.

Ni Haifeng, Shift, 2013, a film component of Voices of the Proletarian, HD video, 07:30 min. film still. Courtesy In Situ Fabienne Leclerc, Paris; Limen Travo, Amsterdam.

There were also two video projections accompanying the installations and sculptures. One, entitled 7:02:53, is a real-time recording of textile dust floating in a darkened environment. With minimal imagery and narrative, the video evokes a sense of nothingness, of the slow flow of time in the long hours of the working day. The other video, entitled Shifts, depicts two workers respectively attending weaving machines in two shifts, with a factory clock hanging high above. When I shot the video, I had the factory clock modified to run fast so that the clock arms could complete a 24-hour cycle within 3 minutes. The scene was shot with an ultra-high-speed camera. I took two eight-second clips and slowed them down to three minutes and 30 seconds, respectively. In the resulting video, each worker’s movements are virtually frozen, almost like he is floating in the air, while the clock overhead seems to be in real time. The video creates a strong visual illusion and perceptual contradiction of simultaneous slowness and fastness, of the immobility of the body, the muted laborer, the endless machines and transient time and life.

Since 2008, I have been visiting another factory in Ningbo (China) on a regular basis, taking a lot of photographs and videos, initially following a documentary approach. The factory was situated in a very idyllic location near a lake, but the workspace and the facilities were very shabby. The factory makes hard molded plastic casings used for packing sex toys sent from China, and all of the workers were women. I ended up making a film, The Flowers of Evil (2012), that focuses on the silver-colored curved, circular and geometrical shapes of the cases that are made to make the objects more desirable.

I was told that the factory produced sex toys under the guise of health-care equipment, so it operated more or less underground. I was intrigued by the apparent contradiction of the work conditions, the unlikely laborers and what the products are intended for, especially when I also discovered that sex toys appeared a century ago as a doctor’s utility for hysteria treatment, gradually becoming a special prosthesis increasingly visible in our everyday life. The consumption of sexual commodities is a huge market-growth area against the backdrop of a widespread tendency in mainstream media toward eroticization and the emergence of a permissive hedonistic culture in which enjoyment is an ideologically inscribed obligation (Žižek). It is in this sense that I want to confront hedonistic culture with something as insignificant as a piece of plastic that evokes a sense of emptiness and futility. The plastic casing comes in as a precise metaphor for the absence of ‘the real thing.’

J.H.F. - So both of these recent pieces focus on setting up some contradictions between our assumptions of productive and leisure time. Our media consumer culture, in its cultivation of pleasure and fetishism, doesn’t really lend itself to this kind of productively paradoxical space. It seems to me, the importance of your pieces is moving from the position of ‘Enjoy your symptom!’ (ala Žižek) to giving viewers a few moments of emptiness, or nonsense, or parafiction, in which to appreciate that paradox.

N.H. - Yes, in our current leisure time there is something of what Žižek calls the lifestyle of ‘coffee without caffeine,’ that any harmful element is removed to ensure a long healthy life. Equally in the social dimension, the only remaining political imagination seems to be a ‘revolution without bloodshed,’ in that all the subversive elements are foreclosed to ensure that our current tandem of capitalism and democracy run smoothly. Perhaps it is precisely because there is not much space for things inassimilable in our sociocultural system that it is all the more urgent to create such spaces.

Jaimey Hamilton Faris is associate professor of critical theory and contemporary art history at the University of Hawai’i Mānoa. She has written articles for Art Journal, October and InVisible Culture and essays for collections published by the Centre Pompidou and Oxford University Press. She also writes criticism for the Honolulu Star-Advertiser and The Offsetter. Her new book, Uncommon Goods: Global Dimensions of the Readymade (Intellect Press 2013), features artists who respond to expanding definitions of the commodity in the contemporary era.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.