“I’ll fain believe this park to be the mirror of your most profound heart, as it implies so many a beauty, I’ll fain believe that my simple trust in you will be no less cherished and protected, than each single plant of your park. There I have read to you from the diary and my letters to Goethe, and you liked to listen; now I give them up to you, protect these pages like your plants, and so again leave unminded the prejudice of those, who before they are acquainted with the book, condemn it as not genuine, and thus deceive themselves of truth. ”

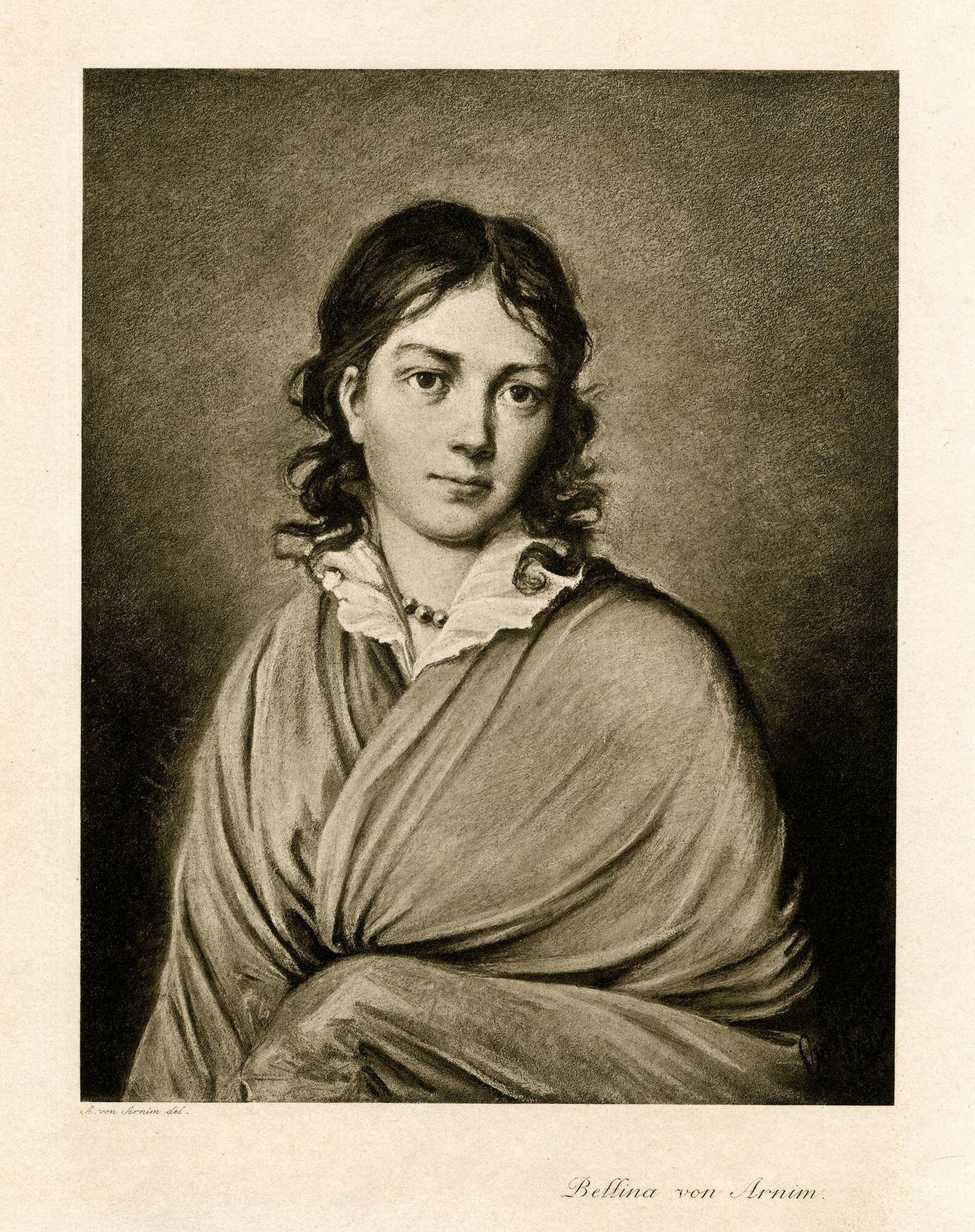

I started researching Bettina von Arnim in 2001, as a member of my PhD trio of women composers. I quickly found that she garnered an astonishing array of opinion from others, with most being either dismissive at best, or downright derogatory. I was asked why I was interested in “that dreadful woman” (an exact quote), or told authoritatively that she wasn’t a very good musician, the implicit message being that she therefore should not be featuring in my music PhD. And - oh look! She’s a secondary figure in Beethoven’s story, so let’s keep her there! In literature circles opinion was a little more positive, though still wary, for reasons I will elucidate. Jan Swafford begins his piece in The Guardian on her by saying that “She was Beethoven's inspiration, Goethe's companion and caught the eye of Napoleon. But many still regard Bettina Brentano as a fraud”, before going on to call her “a one-woman literary movement, at once among the singular and most representative figures of the Romantic century.” It’s indicative of the polarising nature of Bettina and her story. And – oh, look! She’s a secondary figure in Goethe’s story, so let’s keep her there! (I know I keep labouring the point about how central we make being a muse in these women’s stories, but I feel very strongly about this. Men are bad for women’s stories, as they take over the narrative at the expense of the woman’s voice. It can be healthier not to be attached to a male figure at all.)

Bettina is a writer, a storyteller. In dealing with the fractured nature of her life, she is aware that there is an external truth, and an internal, equally valid one. Her writing oscillates between the two, often without warning and without the change being particularly noticeable to an outside eye. Our current aesthetics are much more forgiving of nonlinear descriptions of time, as well as the recognition of subjectivity in all description, and Bettina is certainly unafraid of her own voice. There is a truth in her writing, as Bettina explains in the above quote, but not the kind that people often expect, especially in certain types of writing. Perhaps we could call Bettina an early autoethnographer.

She was born with the grand name of Elisabeth Catharina Ludovica Magdalena Brentano, in Frankfurt-am-Main. Her early life was ruptured by the death of her mother, when Bettina was sent to an Ursuline convent for three years. She tells us little of this experience, save the oft-quoted anecdote of the time she first sees her own reflection in a mirror, aged around twelve:

“I recognized everyone but one, she with fiery eyes, glowing cheeks, with black, finely curling hair; I do not know her, but my heart beats in time with hers, I have already loved such a face in my dreams ... I have to find out more about this being…”

It’s the first story wheeled out to prove Bettina’s penchant for rather wild overstatements and retellings. Those who think this perhaps have little experience of an extreme religious upbringing. I can well imagine the nuns forbidding the mirror as a way into vanity, but also as a result of remnants of the belief that the mirror was where Lilith lived, the stealer of children’s souls.

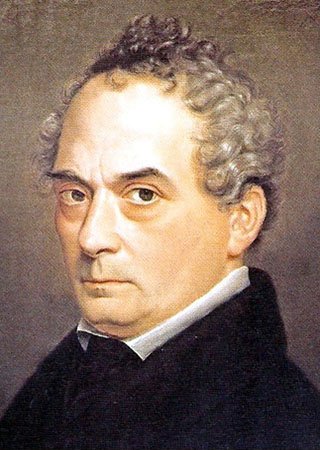

Bettina lived in the convent for three years, until her father died, when she she was sent to live with her grandmother Sophie von la Roche. La Roche was a famous novelist and salonière and thus here Bettina discovered an atmosphere of considerable female achievement. She met the poet Caroline von Günderode in 1799, a friendship that came to an abrupt end in 1806 with Günderode’s suicide, going on to fill the hole with an equally deep friendship with Catharina von Goethe, the mother of the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It’s telling that it was really always women to whom Bettina turned for these deep relationships, and which tend to remain unremarked; when she tried to do this with men, the world recoiled. While still at the convent her seven-years-older brother Clemens Brentano had come to visit her; the relationship would remain close throughout their lives, although as has been oft-noted elsewhere, Clemens spent much time – and ink – in trying to “rein in” the wilder flights of his younger sister. He was, however, the one who would introduce her to much poetry, including Goethe’s, and later, to her husband Achim von Arnim (perhaps best known for his collaboration with Clemens on Das Knaben Wunderhorn).

Bettina studied music in Munich from 1808-9, concentrating on piano, singing and composition. She gained a reputation as an excellent vocal improvisor, something that can be seen in the scraps of melody she later wrote down with the help of different musicians throughout her life. Music, like poetry, was fundamental to her being, these being two of the four pillars she saw as supporting the temple of her creativity. In 1808, she wrote to Achim von Arnim:

“I love music, it is as dear to me as life, it can fulfil me, as does free nature, the summer outside, where no human hand has been at work, but where only the hand of God is discernible, and also Goethe, to whom I mean a great deal and to whom I am refreshing. None of these three could replace you for me, or comfort me, if you were lost to me. But you are not more than they are; so faithful am I and shall remain so forever. You all stand like upright pillars in my heart; when one falls, the whole temple collapses and shatters me.”

In 1805, her brother Clemens Brentano had introduced the two. The three of them enjoyed a close relationship, which eventually became something more between Bettina and Arnim. Even from the beginning, however, their relationship was a complex one. Although Arnim often encouraged Bettina in her creative endeavours, particularly in these early years, this did not always translate into practical help, or even verbal support. Bettina struggled to reconcile her own desire to create literary and musical works with Arnim’s ambivalence towards her work, her roles and her creative relationships with others. By 1810, when Arnim proposed to her, marriage was becoming a central issue for Bettina in social terms, not least because of her age (25), and the death of her grandmother, which made her unmarried state less respectable. However, Bettina was not often influenced by what others thought – she was more concerned with keeping true to her creative self. ‘To remain myself, that is what makes my life valuable, and I want nothing else of earthly riches!’ she wrote to her brother; and later when he reiterated his wish that she marry she replied, ‘I know what I need! I need to keep my freedom!’ Although Bettina considered remaining unmarried and devoting herself to music, the creative exchange with Arnim convinced her that theirs would be a partnership that would allow her to continue to develop avenues for personal expression. At first, this conviction seemed to have a solid basis. Even in 1805, when the two were still addressing each other with the formal Sie, the reciprocal nature of their collaborations is evident. The arrival of seven children and Arnim’s speedy retreat from domestic life, however, inevitable put paid to this. For some years, Bettina was very depressed. A friendship with the young law student Philipp Hössli during the 1820s helped her to resume her creative activities, particularly composition. She also had an idea for a monument to Goethe that could be built. She took this idea to show Goethe in the hope that it would bolster their flagging friendship, but this was not to be. After Achim’s death in 1831, she turned to writing as an outlet. Her best-known book is her first, Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde, a fictionalised account of the correspondence between herself and Goethe. She also published five other books during her lifetime, and a selection of fairytales with her eldest daughter, Gisela Grimm.

The two main relationships for which Bettina is known are, of course, those with Goethe and Beethoven. These have been written of at length elsewhere, including by me, and in the interests of keeping Bettina at the forefront of her own story, it suffices here to say that these were complex. The letters between Bettina and Goethe became the basis for her epistolary book Gothes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde, from which the quotation at the head of this blog comes, and which garnered so much controversy as to its accuracy. (It’s interesting that we’re happy to accept the male eyewitness accounts as true and accurate, while Bettina is dismissed. She feels “overblown”, whereas Goethe retains an aura of reason.) She corresponded too with Beethoven, and tried to make the two men meet in creative harmony. Other acquaintances over the years included with Clara and Robert Schumann, Johanna Kinkel (who was a musical amanuensis for Bettina), Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, and Josef Joachim, who even quoted a song by Bettina in one of his violin concertos. She was acquainted with persons in the other arts too, as well as having a strong political presence. Some of her correspondences were seen to be inflammatory enough that some of the letters (in both directions) were confiscated, and only her acquaintance with King Frederick William IV of Prussia saved her from reprisal.

Her later books continued in the epistolary mould, becoming ever-more political in their subject matter, and culminating in plans for Das Armenbuch, (The Book of the Poor), an indictment of social inequality and plans for addressing this on a large scale. Bettina had never been afraid of being outspoken on social and political issues, and even her sole album of compositions published during her lifetime was an outcome of her political activism. This set of seven songs published in 1842 was dedicated to the music master at the Prussian court, Gaspare Spontini. The Italian composer was the target of political intrigue designed to drive him from his post, and Bettina had written several letters in his support; the dedication of this album was her public declaration of this support. The nine Lieder included solos and duets on texts by Goethe and Achim von Arnim. (There were also two other Lieder published during her lifetime, in music supplements to novels by Achim von Arnim – ‘Romanze’ in Armut, Reichtum, Schuld und Buße der Gräfin Dolores in 1810, and ‘Lied des Schülers’ in Isabella von Ägypten in 1812.)

Although Bettina had plans to set the whole of Faust to music, sketching out an overture at least, her surviving pieces are all songs. She sets not only the song texts from Faust, but also prose passages. The majority of her songs are to texts by Goethe, although Achim von Arnim, Maximiliane Brentano and Amalia von Helvig also feature. Some of these songs were published later by Max Friedlaender, in a heavily version of ten of her songs in the collected edition of her works published in 1920. It was not until Renate Moering’s edition of most of the completed songs, published by Furore in 1996, that these songs were available in Bettina’s own voice.

It is difficult to do justice to Bettina’s multicoloured life in just a few words. She is a kaleidoscope that turns anew with every reading. I end with a quote from her that sums up the entire spectrum of how she saw herself, from creative soul to struggling musician:

“Now it gives me a great deal of joy to compose – hymns to Diana, paeans of praise to Dionysos, translated by Stolberg. Oh yes, it gives me so much joy, in the evening I climb up onto the roof from the laundry, there I invent the most wonderful expressions. The sky blushes in deep empathy, and the stars crowd around and listen, and Hoffmann listens too – he is our closest neighbour. My voice is penetrating, if only my spirit were as well! Hoffmann comes to the lesson the next morning, he already knows my melody half from memory, the part I had written down in pencil he generally knows better than I. We scarcely argue about the metre, because he wants the whole thing to be as I had originally sung it; the beats and upbeats are subordinate and are not allowed to insist on their traditional observance any longer, he says if I apply myself to my studies, then it will open a new path for music. Foolish fellow! He compliments me so that I’m motivated to learn, but even though I know that he is lying to me, it nevertheless carries my enthusiasm to infinite heights!”