Laurie Anderson has been at the forefront of performance art since the early ’70s. She performs solo work and larger ensemble pieces around the world using a wide variety of computer technology.

The following interview was conducted during two visits with Laurie Anderson at her Tribeca loft in New York City in July, 1999. The loft, filled with electronic gear of all kinds, books, nooks, crannies, and intriguing gizmos, overlooks a stretch of the Hudson River waterfront that was often visited by Herman Melville.

Our discussion took place toward the end of her work on Songs and Stories from Moby-Dick, her latest electronic opera. It is scheduled for its New York premier at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in October of 1999.

The interview began with a look at a United States postage stamp and ended with a look at Herman Melville’s personal Bible.

Clifford Ross I found this stamp when I was cleaning out my loft.

Laurie Anderson A stamp, embossed on an envelope—a white whale in a blue oval, and it says “six cents,” “Herman Melville,” “Moby-Dick,” and then under that “United States.” What was it filed under?

CR Well, it wasn’t exactly filed. It was sandwiched between a bunch of other Melville papers and it seemed like a good start for this interview.

LA It’s fantastic. If I were to use that envelope—let’s say we can write to those beyond the grave—I’d write to Herman. And the first thing I would say would be, “Excuse me, I live in the late 20th century. Who am I to read your book and think this book would need to be a multimedia show?”

CR How did a mid-19th century novel become the impetus for a late-20th century electronic opera?

LA More than anything, I love words. They animate everything I’ve done. No matter how many times somebody asks me, “Where do you start, with the word or the image or the music?” I come back to the fact that what really moves me about other people’s work is their language. Whether it’s a piece of music, a computer thing, or even something that doesn’t contain normal language, I put it into language, somehow. If I can put a painting into language, I like it better.

CR In an early sketch for your opera there was a passage, “Make me a mechanical man, 50 feet high in socks. A quarter acre of brains and eyes, no eyes, but put a skylight in and…”

LA He was a Buddhist. Only a Buddhist would say that.

CR He’s speaking for you?

LA Well, yes.

CR I’m curious about the lack of eyes.

LA Let’s say I walk into a new place that’s architecturally incredible. That’s not the first thing I notice. The first thing I notice is air pressure. Just the way my dog sticks her nose into a hole to explore: How big is it? And what is it? How it sounds, how it feels. Only then do my eyes roam, but they’re more directly wired to my brain; sound is wired to my heart. In Moby-Dick, you have a book that has very few descriptions of how things sound. Isn’t that strange for a novel? There’s nothing about how somebody’s voice sounded. But there are many discussions about people’s faces and how they looked against the sky. It’s so visual.

CR But the book itself has a sound.

LA The book is totally musical. The words themselves are the sounds and they have to be read aloud to be heard. All of that rollicking stuff. You know, a paragraph of 18 “s” words: “So one silent and suffusive evening, stars are strolling by.”

CR You said that you would start out your imaginary letter to Melville with an apology: “Who am I to raid your work to make mine?” But a lot of his sounds, and his literary sources, were raided from the Bible—and Shakespeare, Pope, Milton and Dante. Doesn’t your method echo his method?

LA I would change the word “sounds” to “voices,” because in many books it takes a while to learn the author’s voice. Who is this person writing? What’s their point of view? The biggest phony bait in the book is the first three words, “Call me Ishmael.” After that you don’t know who the narrator is because he’s hundreds of people: a historian, an accountant, a preacher, dreamer, observer, naturalist or scientist. You cannot find Melville’s voice in there because he’s just hundreds of different voices.

CR It’s cubist.

LA It’s the most modern kind of narrative style. You will not get to know this author through this book. No way. There is no one Herman Melville for me to write to.

CR You’re in a long line of people who have taken Moby-Dick as the basis for new work.

LA That’s the great thing about the book. There’s room for Patrick Stewart to star in a TV movie as Ahab, and there’s room for William Burroughs. I was talking to someone yesterday about this and they told me to look at Naked Lunch.

CR Did Burroughs quote Melville, or take off from him and head in his own direction?

LA Both of them were ultimately fascinated with authority. They would have plenty to say to each other. (flipping through pages of Naked Lunch) Oh! Look at this: “Gentle reader, we see God through our assholes in a flash bulb of orgasm.”

CR It’s a direct quote from Melville. (laughter) At least the “gentle reader” part.

LA You see? Research is never done. I started by reading Moby-Dick five times and that was just so much fun, pure pleasure.

CR When was that?

LA Three years ago. A TV producer was going to do a CD-ROM for high school kids, a kind of literacy program. On an impulse I said, “Let me give Moby-Dick a shot.” He asked each person to write a monologue about his choice. Supposedly our enthusiasm for a book would inspire kids to read. Robin Williams was doing Dickens; Anna Deveare Smith, Huckleberry Finn; Spalding Gray, Catcher in the Rye. The project never happened, but by the time I read it again I thought, “Wait a second, this is one of the most bizarre things I’ve ever read.” All those long passages about whiteness and rage—“Nobody’s up there!” We know that in the late 20th century. That there’s no one in charge. That there is no plan. We’re on our own. These things are ingrained in us as late-20th century Americans.

CR What about that last passage, where the hawk’s wing gets caught and it’s dragged down to the depths of the sea? It’s hard to believe it’s a random event. Is it orchestrated from the heavens? Does God show his hand at that moment?

LA The biggest question for Melville was, “What if a man outlives the lifetime of his God?” Once you pass beyond the point of thinking that there is anyone up there, well then, how did we get here? Why are we here? And where are we going? What I love is that he has no conclusions, which is the most satisfying conclusion. This scene that we’re talking about—the whale has just smashed the ship, which has sunk with everybody on it. Ahab has wrapped himself around the whale and the whale has escaped. The last thing you see is the top of the mainsail and an arm, nailing a flag onto the mast. Then a bird—and birds, particularly hawks, are messengers in Moby Dick—flies down in between the hammer and the mast. The bird’s wing gets caught and it’s pulled screaming down into the vortex. What an end. It’s a heroic last act: Geronimo, down with the ship. And then there’s this incredible peacefulness.

CR “The great shroud of the sea rolled on…”

LA The magic of the book is that you look for something your whole life, and it represents all sorts of things to you. For Ahab it was the whale, or why the whale took his leg. It took Melville the whole book to say that. But it was summed up in the “Whiteness of the Whale” chapter. Many of the images in the chapter are of absolute beauty, some are of absolute death. It’s a catalog, an encyclopedia of everything. The whale is everything. And so we can read whatever we want into his quest.

CR It makes me think of a wonderful comment of de Kooning’s, when he was describing himself and his work. He called himself a “slipping glimpser.”

LA Nice phrase.

CR Earlier I said Melville’s book was like a cubist construction. He was grappling with this enormous subject, with all these different facets from different points of view. It was so big there couldn’t be a neat conclusion. Your opera has a cubist construction too. You could call it…

LA Performance art!

CR Oh, that’s it. (laughter)

LA Multimedia, multimedia!

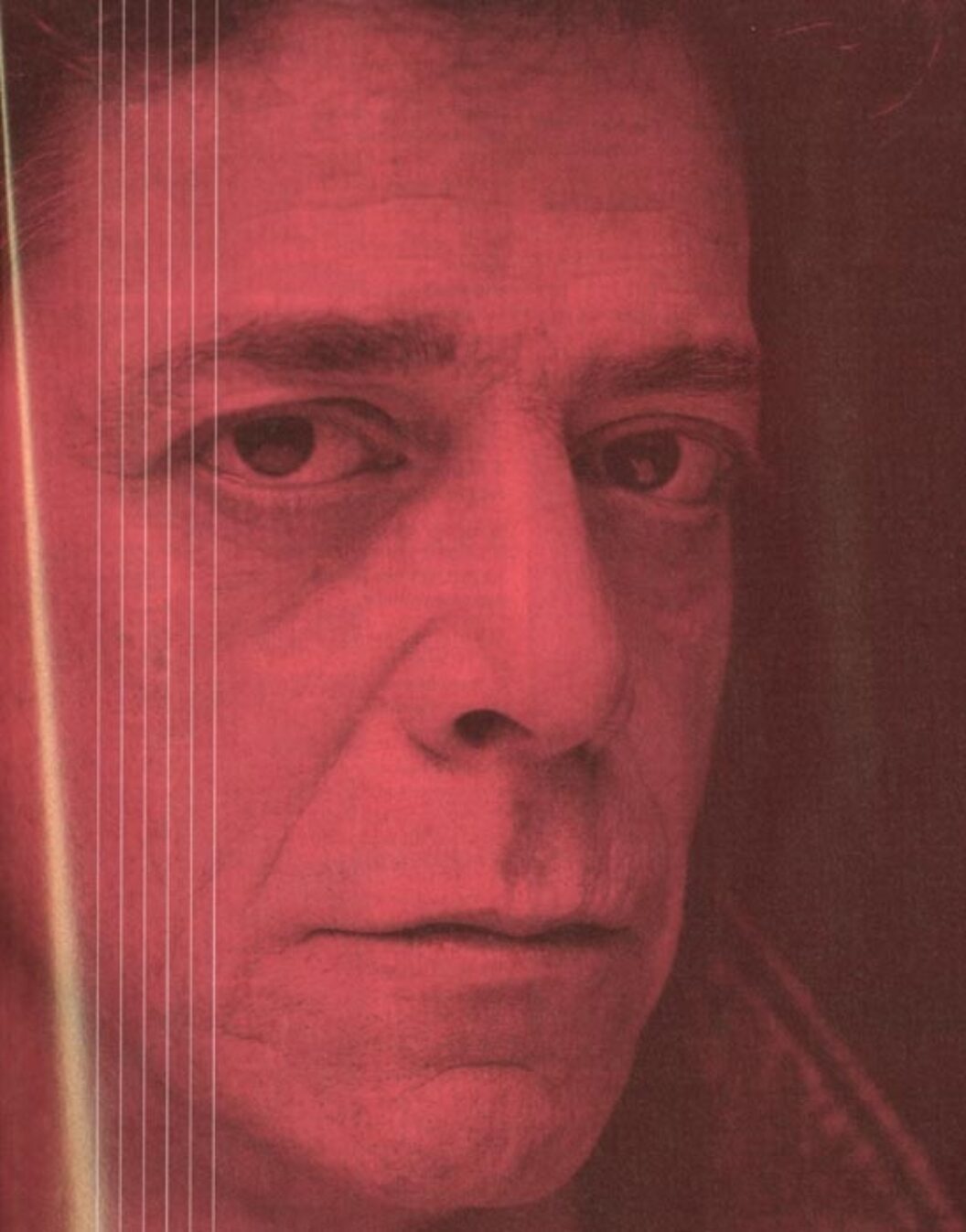

Laurie Anderson. Photo by Neil Selkizk. Courtesy Brooklyn Academy of Music Next Wave Festival.

CR In the latest version, you present scenes from the book, as well as scenes that are your ironic take on Melville—your own riff; you, sitting in an armchair in the British Library, discussing the project. How did you go about constructing your opera?

LA It’s an impossible thing to do, to try to make a book into something like this. Failure is built into the project in a big way because you can’t really represent the book on stage without making it 50 hours long. Then you’d just numb everyone into submission. There were so many heartbreaking decisions to make. I thought, “Well, I have to do the greatest scene, Queequeg and Ishmael in bed.” All the wonderful things in that scene would take at least an hour to do well. And maybe that’s how to present the book: just do one chapter, to really get the flavor of that encounter. It would make a beautiful two hour play. There are so many great and colorful characters in the book. I decided to throw up a white flag and say, “I’m just going to touch on some of the things that I love and not try to tell the whole story because it’s too long.” I thought I would begin to do it justice if I could just get some of the feel of it across.

CR Were there many changes from two or three years ago when you started to work on the project? Melville apparently wrote a terrific potboiler the first go around, discovered a bigger ambition after meeting Hawthorne and basically rewrote the whole book. Were you wrenching things apart and putting the opera back together like Melville?

LA I would rewrite the whole thing if I could, to tell you the truth. I can’t afford to, time- and money-wise. Because in a complicated show like this, to get all of the production systems reworked would be like starting from scratch.

CR I was rather amazed at how fluid the process was, given the large scale at which you’re working. It has changed enormously over time—with all the actors, musicians and technicians pulled along as part of the process. It’s sort of astonishing. It’s not like you’re just sitting at a desk writing a book.

LA I wanted a chance to play with it once I’d seen the whole thing. I’ve done a lot of big shows that involve a lot of equipment and a lot of people, and as much as you try to predict what it’s going to be, you will be wrong. That’s the certainty. What was supposed to be beautiful doesn’t work, so what goes in its place? You’re working with a big palette in a show like this. It involves working really quickly with 25 people and saying, “We’re going to change all of that. Let me show you what my new vision is. Here we go!” Talk about being a captain! You’ve got to get all these people to believe you, because it’s a lot of work even to make one little change.

CR I’d like to read from a letter that Melville wrote to Sarah Moorewood, dated September 19th, 1851. “Concerning my own forthcoming book. Don’t you buy it—don’t you read it, when it does come out, because it is by no means the sort of book for you. It is not a piece of fine feminine Spitalfields silk-but it is of the horrible texture of a fabric that should be woven of ships’ cables and hausers. A Polar wind blows through it, and birds of prey hover over it. Warn all gentle fastidious people from so much as peeping into the book—on risk of a lumbago and sciatics.”

LA What a thing to say about your own book! Can you imagine what he would think about this Xerox we’re looking at? And that we’re just rifling through pages of his personal letters. I wonder if he thought of that, of people 150 years later reading his words.

CR When he was a young man, I’ll bet he had the optimism to think in terms of posterity. But by the end of his life, as he was so beaten down, I wonder if he was thinking that way.

LA You think Billy Budd wasn’t for the ages?

CR I feel that the late work was really personal for him. That he just had to cope with certain issues by writing. Although I guess just by committing his thoughts to paper he was thinking of posterity. But I don’t see how he could have held out any hope that his work would be remembered. He was completely forgotten as a literary figure by the end of his life.

LA As a late-20th century American, I think about how much we have in common with Moby-Dick, in terms of obsession, love of work, love of details. The concept of the crazy captain is not an unfamiliar one to Americans.

CR You mean Richard Nixon?

LA Yes. And Ronald Reagan, George Bush, Bill Clinton. These guys are out of their minds, and we’re traveling along thinking, “Yes, the guy in charge is out of his mind.” And if he’s not out of his mind by the time he’s in office, he is going to be in short order, believe me. I think Melville always questioned authority. But the biggest thing that links us to him is our being naive enough to ask, “What are we doing here?” That’s really what Melville was asking. If you don’t believe in authority, like Ahab, then you are your own authority. You make your own rules. What does nature mean without God? Will life crush you like a bug, or do you stand up and say, “I will not be crushed. I believe in nothing, but I won’t be crushed.” People are disillusioned by the speed revolution. We’re moving faster and have access to everything, but spend all our time running. Everybody I know works harder now than they used to, and longer hours. I chalk up some of my view to nostalgia for the good old days when I sat around and dreamed. In the ‘50s, a guy who sold insurance sold insurance his whole life. He died selling insurance—and that was his job. Now people do that for three years and then they go and do something else and then they don’t know what they’re going to do. I don’t look around me and see happy, contented people. I look around and see anxious workaholics. Many spiritual movements in this country are growing in response to that. There’s so much longing for the ideas of our transcendental ancestors, like Emerson or Thoreau. It’s the new land for Buddhism. Maybe there is an invisible world we can’t see. You ask a French person, “Why do you live?” and he answers, “To drink wine and eat cheese and make love and have fun. Why would you ask a stupid question like that?” I bet there’s something else out there that gives us meaning.

CR Do you think people were in the same state in 1850?

LA Melville was.

CR That reinforces the idea that Moby-Dick is 19th century hi-tech. All that whaling paraphernalia was their hardware and software. Do you think they had the same feeling—that things were going faster and faster and leading nowhere? Is whaling just a chase without end?

LA It’s a job. It’s a workingman’s book, starring guys who are working. It’s not Goethe, where a hero goes out, is challenged and learns things. These men work hard, and they sail, and they drown. And it’s not just that they’re going to drown, it’s that they’re being led by a madman who they don’t understand and they follow him because he has unbelievable charisma. He knows what he’s looking for. How do you drive men to action? You get some really good bait and dangle it in front of their eyes. Ahab did not have great respect for his crew; he thought they’d only respond to money. Now that is the great American story.

CR The only explanation that I found in the book for why they kept going was the golden Spanish coin. Of course it’s a ridiculous incentive. Were Tashtego, Queequeg or Stubb after that gold coin? Or were they swept up by something exciting and abstract? Did the whale become their goal, too, by proximity to Ahab’s crazed, infectious drive?

LA They basically forgot what they were doing for several hundred pages. Time and place are gone in this book, they’re lost from the first minute they get out of Nantucket.

CR What keeps them going?

LA What keeps anyone going? When your alarm clock rings, you don’t get up and say, Why am I in the world? You get up because you have to be at your job on time. It’s simpler to think of small things.

CR When Melville was writing, do you think that he wanted the reader to experience the book through Ahab, or Ishmael? Whose journey is it?

LA I think we’re meant to be omniscient in ways that many readers would never want to be. You only see from Ishmael’s point of view initially. Around page 100, when they ship out, it becomes a collection of essays and the thread is Ahab, but it’s no longer really a story. It’s an adventure on a certain level, but raising and lowering sails doesn’t advance a story. In fact, the story itself is rather static. Ahab is crazy from the beginning and he doesn’t really change, except a tiny bit at the end.

CR Did the lack of a traditional narrative make this book more interesting to you? Or did it create a problem? Or both?

LA That was the biggest problem for me. I initially wanted my piece to be a dream about the book—a dream dealing with some of the ways it made me feel. But, once you bring in actors, they ask, “Who am I?” And there is no single answer. Anyway, I don’t really know what the book means.

CR Did you start your project thinking you knew?

LA I went into it thinking that I could find a way to express Ahab’s anger, the kind of fury I’ve never felt myself. That’s why I’ve had such a hard time, because I don’t feel the anger that drives it. Without anger a lot of the story isn’t there. There’s a lot that’s incredibly beautiful. The writing, the ideas and colorfulness. But until I find the anger in myself that connects to the anger in the book, I’ll never finish the project. But then I’ve never finished anything.

CR To me, one of the strangest aftereffects of reading the book is that my memory of it centers on beauty, not anger and darkness. The beauty of the language and the images. And your opera is filled with extraordinarily beautiful sections, and funny, ironic passages, all wrapping up Ahab’s anger in a cocoon. My memory of your Moby-Dick is also centered on beauty.

LA I reacted to the beauty of the book, Melville’s crazy way of looking at the world. It’s made up of these fabulous short stories that are full of images and ideas that are so crazy and beautiful—polar bears walking on ice floes, tiptoeing across them, tilting them as they walk. Somebody canoeing through the Everglades…I fell in love with the book, but the big question—what the whale means, all that anger and revenge—leads us back to the Bible. It’s the core of the puzzle. His own Bible is a beautiful, stamped leather book—looking at it sends a chill up my spine. He wrote his name on the second page. And then halfway through the book, right before the New Testament, are the birth dates of his wife, his daughter and his boys.

CR He had purchased it a week or two before he started work on Moby-Dick. He clearly bought it to gird himself, arm himself for what he was about to do.

LA More startling than anything were his pencil marks in the margins. When I saw them, that’s when I really lost it. What about this myth that his wife erased some of the marks?

CR It’s not really clear what happened. It’s established that he was a pretty bad husband and not a very nice guy. There is some thought that out of either embarrassment over the things he wrote, or perhaps as vengeance, his wife may have erased some of his notations.

LA I’ve never had a feeling like this about an object. I got out my magnifying glass and just opened every page of that book to look for little marks and notations. And of course I’m looking for any reference to the word “whale.” So I’m looking for a whale with a magnifying glass. And I found it. I found it, except it was not a whale. “Very like a whale,” as he says in the beginning of Moby-Dick, but not quite a whale. He marked a passage in Isaiah 27, verse one. "In that day the Lord with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish Leviathan the piercing serpent, even Leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea." And I just completely flipped out. You know sometimes you wish you could sort of stand aside and just look at yourself screaming at the top of your lungs. Suddenly it was totally apparent to me what the whole book was about. The whale was a snake and the ocean was his garden. That’s how Melville was working out good and evil. Through a whale which, if you take all the blubber off—really stripped things down—is a snake. (turning pages) Here is another part he liked, Isaiah, it’s all marked with underlining and checks and Xs. Quite a lot of vipers and fiery, flying serpents. What incredibly brutal language. Melville was writing about Jehovah, Yahweh. He was not writing about Jesus. I think in Billy Budd he wrote about Jesus and his suffering, but his references in Moby-Dick dig deep into the pyramids. And there is the kernel of Jehovah, the righteous, the angry one. Punishment is a pretty big theme.

CR How about the markings in Isaiah 34, verse 14?

LA “The wild beasts of the desert shall also move with the wild beasts of the island and the satyr will cry to its fellow. This creature will also rest here and find for herself a place of rest.” I used part of that text a few years ago in the object I made called Tilt. It’s a music box that was originally going to be a duet between a man and a woman. I love using preexisting tools, and in this case it was a carpenter’s level. I was originally a sculptor. But I thought, There are enough forms in the world. Everyone wanted to make more shapes and I thought there were enough shapes; I figured, Let’s take existing forms and make them mean something else. So in Tilt, the carpenter’s level becomes a music box. It tilts one way and the man sings, it tilts the other way and the woman sings. When it’s level they sing together.

CR So in Tilt you recycled the object and gave it a new purpose and a new meaning. Was your use of Moby-Dick another form of recycling? As Melville recycled the Bible to create Moby-Dick?

LA I don’t think of it as recycling at all. Everything for me is new. A tool that sings to me when I pick it up is different from a tool I use to build my desk. They happen to look the same. But people look the same. We have two eyes, a nose and a mouth. We couldn’t be more different.

But back to the Bible: the Sermon on the Mount. “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.” I think Richard Nonas was thinking of the Sermon on the Mount when he told me it was okay to be an artist. I was out of art school and I was complaining all the time about paying my rent: How am I going to eat? How am I going to go on? He said, “You’ve got it all wrong. First you have to say, ‘What do I want to make as an artist? What do I want to do as an artist?’ These other things are unimportant—they’ll happen anyway. Once you get your priorities straight, you’ll be surprised what happens.”

CR Was Nonas your teacher?

LA No, he was a friend, an older artist that I respected. I was afraid to call myself an artist. And he said, “That’s ridiculous. What do you want to do? Lets talk about that.” What a fabulous guy. It’s wonderful advice.

Anyway, let’s go back to the lilies of the field. When Melville writes, “consider the subtleness of the sea,” he goes into a very dark world about the invention of sharks. How these dreaded creatures glide underwater and how they will eat you alive. Who made these man-eating engines? All they do is rip flesh apart. As Queequeg said, “What devil god invented that? Are you worshipping that god?” And when Melville wrote, “Consider the subtleness of the sea,” his 19th century readers, who were familiar with the Bible, got his subtle reference to “consider the lilies of the field.” This is not just a God who created good things. This is a God who created good and evil and gave you a choice.

I wanted to get in another idea that fascinated me, of when I first saw what I would call the Southern Jesus, the painted Jesus. Like most Protestants I grew up with the Northern Jesus who would teach you things about how to be kind to your neighbor. Things that were really in your self interest—good citizen kinds of things: help other people, do unto other people as you would have them do unto you. Be kind. It was not so much hellfire as advice on how to live a good life, and be fair. And he’d do a few magic tricks once in awhile (laughter), like raising the dead, things like that—to add credibility to his advice.

When I was terrified as a child, it was by a God who was really scary, my grandmother’s God. She was a holy roller Baptist who talked in tongues. And her God was Jehovah. Anyone who didn’t think the way she did was going to fry in hell. She was obsessed with sin, obsessed with evil, and saw them everywhere.

But when I went to Europe the first time, I saw another Jesus entirely. This Jesus was not talking. He was either a little boy in his mother’s arms, or he was dead. Either way, he wasn’t giving you any advice whatsoever. He was giving his life for you on the cross, or being held. Or both, as in the Pietá. A man of sorrow and pity being held by his mother. Dead. Speechless. And this is how the arc of Melville’s work from Moby-Dick to Billy Budd follows a course that I can relate to. From this terrifying man who would be God, Ahab—to a man, Billy, who would die for you.

CR A man of supreme arrogance who would bring you to your death in the service of his obsession, to a man who is totally humble and giving.

LA Billy Budd was about sweetness.

CR Given how bitter Melville became, and how isolated, it’s kind of amazing that Billy Buddwas his final testament. It’s a triumph of the spirit to have viewed things that way at the end of his hard life.

LA I like to think of it that way. Who knows how it was, really? Perhaps it was just a mean man scribbling a beautiful story. There certainly is a sweetness in his writing and a longing, an incredible longing. Melville’s last character was Billy—one who would absorb all pain, take the blame for everything, sacrifice himself… But the whale. There was even selflessness in the whale. Melville says, “Let’s all try to be more like a whale. Be cool at the equator, be warm at the poles. Keep your own council. Don’t be affected by stuff.” It’s like some Buddhist master was writing part of Moby-Dick. So even though he’s talking about the giant force of nature, it is one that is beyond good and evil. It’s a force of nature, period. It was Ahab that made the whale into evil. The question is: Why do we create monsters? When we finally find them, what do we do with them? In most monster movies, they kill the monster. Monster movies are medieval tales: the hero slays the dragon from the sea.

CR Are there any stories, other than Moby-Dick, where the monster wins the battle?

LA Let’s see. I think in some Japanese King Kong movies. Doesn’t the monster win there?

CR That might be a great place to end this interview.

LA Yes, it’s always good to end with a question.