ArtSeen

Does Nordic Art Exist? A Lesson In Transculture

The term “Nordic” includes the three Scandinavian countries in northern Europe— Denmark, Sweden, and Norway—as well as Iceland in the mid-Atlantic and Finland. While Iceland is linguistically related to northern Europe, Finland is not. Although Finland shares a geographical grouping with Scandinavia at the western edge (near Russia), its language is less related to the Scandinavian tongue than to Hungarian or Basque, which is closer to its origins. Having visited four of the five countries (I am scheduled for a trip to the fifth, Norway, in early 2012), I would argue that each of these Nordic countries shares one common attribute: they still care about the quality of life, and fundamentally understand that this quality endures because each citizen requires it, even if some will inevitably maintain a higher material standard of living than others. Unlike Americans, the Nordic people know the difference between enjoying everyday life and possessing material wealth. The two are not the same. Still, the standards of egalitarianism are such that every citizen is given full health coverage, quality compulsory education, and safe, regularly maintained roads and bridges. They complain about taxes, primarily to assuage the expectations of Americans, whose materialism they share, but whose greed they find perplexing, somewhat narcissistic, and, in some cases, oddly self-destructive.

Curated by Robert Storr and Francesca Pietropaolo, North by New York: New Nordic Art is a relatively modest exhibition, refreshingly spirited and carefully constructed. The larger point, as I understand from the catalog essay, introduced by Storr and Pietropaolo, is that globalism has no particular relevance in art today any more than terms borrowed from early modernism, such as “international” or “universal.” Given the current crossover between ideas and materials, artists are more likely to engage in “hybridities” rather than singular mediumistic approaches. Thus, Nordic art cannot be reduced to a single defining characteristic any more than art in the Middle East, Latin America, South Africa, or Central Europe. One of the challenges in trying to pinpoint theory in relation to art is to construct an argument that functions openly, while being diverse enough to account accurately for all the works in an exhibition. The trick is to avoid a formulaic or illustrational discourse where each artist is given an explanatory paragraph of equal word-length with a generalized summation at the conclusion. There has to be a better way of elucidating one’s curatorial aspirations—a point argued in the publication Tema Celeste nearly two decades ago where I raised the question: “What is a Group Show?” While catalog essays for such exhibitions presumably intend to describe the work and objectively promote the roster of artists, the expectations given to a reviewer are more likely about selecting works based on experiential criteria and identifying how these works may or may not relate to the stated purpose of the exhibition.

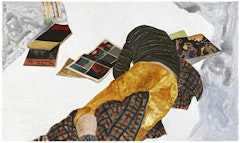

Given the range of “new media” included in North by New York, including conceptual photography by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, film stills by Finnish artist Marja Viitahuhta, and the video works of Danish artist Henrik Lund Jørgensen, the fact that actual paintings are included among the hydridities present in the show is already ahead of the game. The paintings are primarily figurative with psychological overtones, as experienced in the intimate subjects of Karin Mamma Andersson and in the more distant portraits of Gunnel Wahlstrand. A third Swedish painter, Sara-Vide Ericson, younger than Andersson and Wahlstrand, indulges in a figurative style partially reminiscent of the painter Marlene Dumas. Ericson’s most successful work, “Liar VIII” (2010) breaks free of influences and focuses on hard-light expressionism depicting a potentially violent dramaturgical incident in which one figure appears on the verge of choking another in an open landscape. Ericson’s clear spatial divisions suggest Ukiyo-e printmaking and give the painting a certain intensity wherein form and color play off one another.

The only painter in the exhibition who leans toward abstraction by way of landscape is the Danish artist, Per Kirkeby. His focused, unencumbered brushwork and equivocal dark and light saturations of color resound with a clarity of purpose. His compositions emerge as bold, largely because they defy the determinacy of any surface organization. He favors evenly spaced applications of paint combined with staccato markings over the colors dominating various sections of his paintings. The all-over effect offers a seductive originality that invites a resounding sensory involvement. Kirkeby’s untitled vertical painting from 2010, included in the exhibition, loses none of the energy of the fiercely exuberant paintings he showed frequently in New York during the 1980s. Another painter, this time of Danish-Israeli origin, Tal R, reveals bold, bright colors in his street scenes, such as “People from Clock” (2009), and other folk-related paintings. Here the hybridity of design, color, and social comment exceeds the limits of a singular interpretation, often evoking semiotic disjunctures or autosymbolic metaphors within the context of strange psycho-sociological encounters between people.

One of the most striking mixed media works in the exhibition was a multiple projection piece, titled “Mieskuoro Huutajat”, or “Screaming Men’s Choir,” in which various speakers and screamers, donned in dark suits and neckties, deliver “Sorry Speech” (2010). Founded and directed by the Finnish avant-garde composer Petri Sirviö in 1987, originally to re-interpret well-known folk songs by singing the words at excruciating volumes, the choir has here reinterpreted a speech given by Australia’s Prime Minister Kevin Rudd simply by screaming at intervals in his apologies to the aboriginal population for exploiting their land and intruding upon their sacred sites. The irony of the choir’s antics is obvious, as it projects sentiment into the absurd and beyond, thus offering a political comment that provokes the white man’s repression, rage, and insincerity, revealing the speech’s underside as an inflammatory racial testimony. “Mieskuro Huutajat” makes clear that for art to enter into a global dialogue, it may borrow from other cultures, but somehow culture must reveal itself in the form of transculture. This would also be true in the large-scale banners of Japanese calligraphy—spelling “anger” —by Norwegian artist Gardar Eide Einarsson, the political video spoofs enacted by the Spanish/Icelandic dyad Libia Castro and Olafur Olafsson, or the mock photographs by Saana Wang. The paradox is that while artists continue to move through cultures that may be foreign or “outside” their own, they are, in many ways, reinforcing traits that are indigenous to their own. In contrast, in a work titled “Histories for the Future” (2008/2011), Cecilia Edefalk has developed a series of multimedia ruminations where she “speaks” and “sees” as if appropriating from the 19th century Swedish mystical writer August Strindberg. In another series of works, Norwegian artist Marte Aas photographs “natural” environments in her homeland. In either case, one might say these artists are involved with evolving cultural concerns, whether psychological or ecological, that speak through, and yet beyond, a particular time and space. Thus, the problems of transculture in one’s artistic practice—as it is called today—may focus either on the Other as a source of identity, or on one’s changing sense of Being in relation to indigenous forms of culture. Yet, there is a third factor as well, which Marte Aas indirectly points to, and that is the encroachment of globalization through economic development in places where such terminal effects are destroying our sense of place and time. We might refer to this as a type of ersatz culture, where the experiential process of transcultural is somehow inhibited or thwarted from entering into a more habitable exchange of signs within the global village.