ArtSeen

MARK GREENWOLD Murdering the World, Paintings and Drawings 2007–2013

On View

Sperone Westwater GalleryMay 10 – June 28, 2013

New York

One of the profound pleasures of encountering great art is the detangling of endless threads of reference in one’s mind. This process began the minute I walked away from Mark Greenwold’s current exhibit at Sperone Westwater, and I began to unravel the cluster very slowly.

Each painting by Greenwold is complexly complicated—or perhaps, one could say, complicatedly complex. Complexly complicated because the artist barely appears able to relate the content of his paintings to how each narrative reflects his complicated relationship with the world. Complicatedly complex because his appetite for art and art history is as multi-dimensional as Greenwold is himself: he thrives on all things uneasy as they offer boundless potential subjects for his art. Either way, his works are remarkably contradictory to what has been cultivated in painting culture for at least the last three decades. In the epigraph of the exhibit’s catalogue, Stanley Cavell states, “The cause of tragedy is that we would rather murder the world than permit it to expose us to change,” which evokes Max J. Friedlander’s famous remark, “It’s easier to change your worldview than the way you hold your spoon.” The inevitable change is longed for, yet attainable. I was struck by Greenwold’s response in an interview with fellow painter Carroll Dunham published in the catalogue, when asked for his definition of humanism: “I always thought Woody Allen movies that Woody Allen was in were better because he was in them. But he seems to get too old to play that character. I’m not; I’m interested in being old and being in my paintings also. It seems like old age is [a] great subject matter.”

A few things rushed to mind as I took my time walking from the Bowery to the L train at Union Square. First, after Sigmund Freud came to America in 1909—his first and only time—to deliver his five lectures on the theories of psychoanalysis at Clark University, he subsequently became disdainful towards Americans because of their obsession with money and power as substitutes for sexual fulfillment. Second, Franz Kafka, who never came to America, began the first chapter of his unfinished novel Amerika in 1912, which was published three years after his death in 1927. Third, in 1921, Balthus, at the age of 13, published his illustrated book Mitsou, with the preface by Rainer Maria Rilke, about a boy who finds and loses his cat.

With their repeated penetration of lines, Greenwold’s new paintings and drawings evoke Giacometti’s existential angst, while the calibration of scale among figures, objects, interiors, and landscapes conjures Balthus’s magnified psychological space. It’s notable that Greenwold achieves this synthesis despite his reliance on photographic sources, as opposed to Balthus’s and Giacometti’s use of direct observation. Greenwold gathers material for each painting by selecting fragmented reproductions of objects or interiors from design or architecture magazines for the backgrounds, and his own photos for the figures. While reflecting on this issue of searching for an ideal environment, which is constructed from other fragments of places and times, I remembered how Kafka seemed to imagine his characters and places in his mind’s eye rather than in specific locales; in Amerika, Karl Rossmann imagines the U.S. as a land of infinite possibility where everyone succeeds beyond his or her own dreams and fails beyond their wildest horrors. The novel ostensibly ends with Rossmann on the train heading out to work for the Nature Theater of Oklahoma. Greenwold, too, has created his own theater of the absurd, though anti-nature and with a bent of humor and optimism.

Next is Freud’s concept of psychosexual development, which he divided into five stages: oral begins from birth to 2 years old; anal from 2 to 3; phallic, which deals with the genitals (Oedipus complex in boys, and thanks to Jung, Electra complex in girls), from 4 to 6; Latency, which focuses on dormant sexual feelings, from 4 to 10; and Genital, the maturation of sexual interest, from puberty into adulthood. One implication of the latter is that one’s adolescence can be extended forever (as when grown-ups get embarrassed when they act like children). Puritanical American systems of judgment are more prone to misunderstand the sensual and open eroticism in Balthus’s painting. Conversely, European cultures, particularly modern English and French writers and artists, are aware that the extremely sensitive world of children merits respect, that it is equally complex as that of adults. Charles Baudelaire, Marcel Proust, Alain Fournier, Colette, St. Exupéry, among many others, have explored the theme of children’s imagination. It’s clear that in Mitsu, Balthus was not just the boy looking for his cat with such determination, but was the cat. By identifying with the cat (as in his 1935 painting “The King of Cats”), a creature that makes unpredictable turns from affectionate to unapproachable, Balthus found a vehicle to perpetuate a mystery about himself. It was also during this same period, around 1922, that Balthus made a vow to remain a child forever, reaffirmed when he chose to illustrate only the first half of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights when Heathcliff and Cathy were most happy, and from when Balthus’s inner world became willfully solidified.

Greenwold is just as intensely invested in his pictorial ambition to simultaneously intersperse form and content as Balthus had been. They both went against the grain of their times; while Balthus was painting in the height of Cubism’s popularity, Greenwold began his career during the dominance of Pop Art and Minimalism. (Through thick and thin, both kept their visions intact.) Both have a sophisticated rapport with art history: Balthus revered the monumental frescoes of Piero della Francesca; Greenwold prefers Sienese small-scale, egg-tempera panel paintings and the intimacy of early Dutch painting, especially Jan van Eyck. Yet both have also been able to extrapolate and incorporate formal aspects of the art of their time into their own work. I suspect among the few differences between them would be, for example, Balthus’s obsession with English novels, particularly those of Emily Brontë, versus Greenwold’s passion for European and American Jewish literature, Kafka and Saul Bellow in particular; or the size of the paintings, Balthus large, Greenwold small; or the age of the subjects—Balthus refused to grow up and hence only painted adolescent girls in various personifications of Cathy with a few exceptions of self-portraits, especially one in which he appears as Heathcliff at the age of 27, sitting to the left while Cathy is being combed by an old maid in “Cathy Dressing” (1933). Greenwold can’t wait to put himself in his painting as soon as he understands Freud, or devours Kafka, Bellow, and other Jewish writers. All of the above has given Greenwold the necessary arsenal to deal with all aspects of his life, from good to bad, beauty to ugliness, humor to tragedy, and real to unreal, as if undertaking the dissection of his own mind in order to describe each of his characters’ emotions and physiognomy with wit and energy. Each is laid bare in his paintings, quite akin to Bellow’s principled characters, who in spite of the constant negative forces of society and circumstance are potentially endowed with heroic capacities.

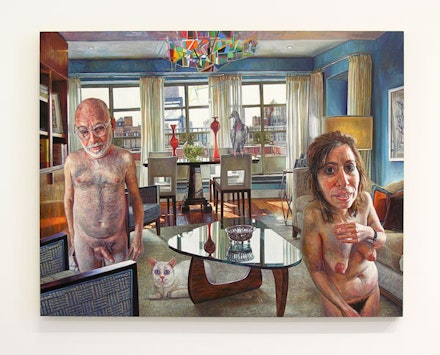

Meanwhile, Greenwold’s ferocious formal and painterly aspiration is matched to his complex and picaresque narratives. For example, the sophisticated network of brushstrokes in “A Jewish Couple” (2011) displays a variety of touches that accommodate endless differences of surface: from the eccentric cross-hatched flesh of the two naked figures, contrasted wonderfully with the evenly painted carpet; to the white reflection on the glass of the table top, vastly dissimilar to the white reflection in between the window frames; to the bold and relatively thick brush strokes on the upper part of the back wall and ceiling, which visually soften the tightly painted geometric/abstract configuration hovering in the middle of the ceiling. The extended use of cobalt blue and turquoise, mixed in with other colors, even with earth pigments and black to make subtle shades of cool gray, have more tightly integrated and lightened the palette than ever before. In addition, the rhythm of the paintings and their spatial construction seems to suggest Greenwold’s willingness to experiment with greater frameworks of geometry, greater speed, and greater pleasure. In “A Jewish Couple” displaying the orthogonals and transversals of the perspective dictates the interplay between flatness and depth of the painting. While the two naked figures (the self-portrait standing in full-frontal view on the left with the head looking down towards slight left, and the female figure on the right, half-cropped by the bottom of the painting, leaning forward in three-quarter view) frame the space between them as much as inviting the viewer into the painting. Had Greenwold’s erect penis not moved to the left, parallel to the two arm rests of the sofa in front of him, the whole space would have been much less generative. (It would have been less interesting had he painted the above as a biomorphic abstraction rather than a geometric one.)

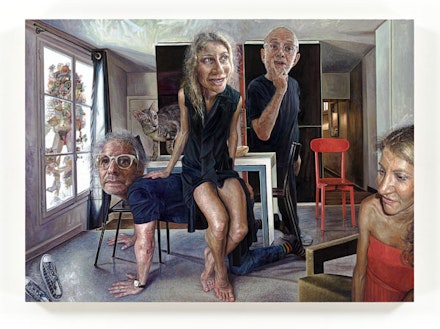

As weirdly delirious as some of the paintings appear, such as “Mean Old Man” (2012–13), “The Banker’s Daughter” (2009–10), or “Men” (2009), the two most complex paintings in the exhibit, for me at least, are “As a Man Grows Older” (2010–11) and “Good Fortune (After Aristotle Ridden by Phyllis)” (2013). Although the former is spatially compressed and packed with dispersed figures and objects, and the latter is more stable, less cluttered in its composition, they both deploy cubism—the depiction of space from different angles simultaneously—with straight-on, eye-level angles oriented up/down/sideways, as well as the occasional flattened or tilted picture plane, which evocatively increases degrees of disorientation in some cases and stability in others.

In the end, a definite sense of wonder and pleasure is conveyed, as much for the painter as for the viewer. I laughed out loud many times. Clearly Greenwold is allowing himself the exploration of new painterly invention. He’s extended his repertoire of human expressions and postures; explored more unexpected compositional devices (which would be impossible if he painted from direct observation); widened his range of painted surfaces; expanded his interplay between biomorphic and geometric abstraction; and imbued his painted pets with that extra edge of charming insanity. This new marriage of ultimate egocentrism and animism is evident in this important exhibition. Perhaps by unremittingly portraying himself as an older man, exposing his vulnerability and nakedness, Mark Greenwold has become a child again.

257 Bowery // NY, NY