ArtSeen

XU BING Phoenix: Xu Bing at the Cathedral

New York

The Cathedral Of St. John The DivineJanuary 2014 – March 2015

Since last winter, a formidable presence has resounded across the cavernous interior of The Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Upper Manhattan. It is not that of the divine, although that too is surely there. This presence is that of two mammoth birds created by Chinese artist Xu Bing. Suspended from the cathedral’s vaulted ceiling by an elaborate rigging system almost as wondrous as the massive pendants in its charge, the beasts, collectively titled “Phoenix” (2008 – 10), conspire with their host to create a commanding appeal for hope and unity in a time widely marked by their absence. If the cathedral’s lifeblood is the salvific power of the transcendent, the salvation heralded by these creatures is to be found in the transformative potential of human ingenuity. Though not its intended context, the cathedral lends the work a dimension of meaning that both universalizes and expands upon its original intentions. Here, art, social activism, and the spiritual fuse to create a force so compelling we might wonder why they were ever dissociated.

The story of the work’s commission is inseparable from its meaning. Having been asked to create a large-scale sculpture for the atrium of a high-rise being erected in Beijing, Xu visited the site and was shaken by the deplorable working conditions of its migrant laborers. Responding to the glaring discrepancy between these workers’ plight and the luxurious lifestyle the product of their labor would afford others, he conceived a piece that would be both a monument to the sacrifices of these men and a commentary on the larger issue of China’s increasing urbanization. “Phoenix” was to be made entirely of industrial tools and detritus gathered from the building’s construction site and would take the form of the two-fold phoenix of Chinese legend: a male and female pair symbolic of unity and good fortune. Although the proposal was initially approved, the building’s developers backed out after the financial crisis of 2008, apprehensive about what kind of statement such a raw and politically charged work might make in the freshly bruised country. Only after the intervention of a private collector was the work eventually realized, now with materials gathered from construction sites across Beijing and the assistance of a large team of migrant laborers. Finally completed in 2010, the creatures have since become birds of passage; after being shown twice in China they flew to the States, stopping for a year at MASS MoCA before coming to New York.

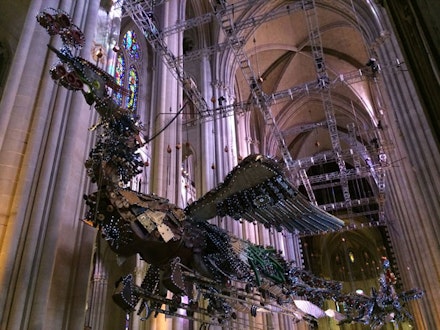

But knowing the birds’ story does little to prepare one for the experience of seeing them. Entering the immense, Gothic-style building, one is immediately dwarfed by vastness. At nearly 140 feet high, the nave’s canopy towers overhead, inducing a mood of hushed reverence and humility. Looking up being the immediate impulse, it is the “supergrid” that one sees first: a spectacularly baroque system of metal trusses, cables, and pulleys that hangs halfway down the nave. Suspended from it, and hovering 12 feet from the ground, are Feng and Huang, the two creatures whose unison forms the Chinese Fenghuang. Each about 100 feet long and weighing a combined total of 12 tons, the birds are a wonder to behold.

Sacred and benevolent though they may be, polite these birds are not. Instead of opulent feathers and their Sunday best, they don stained, scarred, and mud-caked vestments. Not merely adorning their bodies but indeed composing them are countless pipes, shovels, tire rims, jackhammers, saws, pliers, and drills, all meticulously arranged to conform to ornithoid anatomy and fastened together with the utmost precision. Neither are they without humor: instead of talons, they boast rusted steel claw scoops that they keep daintily curled up against their breasts. Hard hats, fire extinguishers, fans, and goggles: Feng and Huang have left nothing behind. Fierce, raw, and redolent of earth and sweat, these birds exude strength—and, above all, pride. As if to underscore the latter sentiment, tiny white lights lace their entire forms, turning the beasts into majestic constellations at night.

Gazing up at the tremendous pair, one cannot but feel the presence of the Chinese laborers whose hands must have touched every inch of these tools. Theirs isn’t the only unseen human presence, however. With labor in mind, one can hardly fail to wonder about those who built not just the suspension system but the cathedral itself, both testaments to human might in their own right. So rarely do we consider the untold numbers whose fortitude and ingenuity created the structures we take for granted, so thoroughly has all evidence of their struggles been expunged from our lives.

More seldom still does one think of collective labor as a spiritual matter—especially in the artworld, where one seldom thinks of the spiritual at all. But with its plea for unity in the context of a religious atmosphere, “Phoenix” suggests a kind of communion of which even the staunchest atheist can partake: that which can be achieved through binding ourselves together in collective action toward a common goal. If people working together can create sublime works of art, engineering, and architecture, why can we not do the same toward a more just and conscionable world? We mustn’t wait for divine intervention, “Phoenix” seems to admonish. Together, we can achieve transformation right here in the gritty realities of concrete and asphalt. Significantly, Feng and Huang do not face the cathedral’s altar. Instead, they face the street, perhaps pointing our way to the work that needs to be done.

Contributor

Taney RonigerTaney Ronigeris an artist, writer, and frequent Rail contributor. www.concatenations.org

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

Anne Patterson: Divine Pathways

By Amanda Millet-SorsaDEC 23-JAN 24 | ArtSeen

The Cathedral of Saint John the Divine on the Upper West Side of Manhattan serves both as a spiritual sanctuary and a cultural one, with a dedicated program to visual arts and music. Divine Pathways (2023) is Anne Patterson’s newest installation in a place of worship, coming ten years after Graced With Light (2013) in the Grace Cathedral of San Francisco.