ArtSeen

ISRAEL LUND / AMY GRANAT

On View

David LewisSeptember 8 – October 29, 2017

New York

“Two wrongs can make a right,” “what you see is what you get,” and all sorts of impenetrable truths and blatant cliches are up for grabs in the maelstrom of data and dots in this well paired exhibition of Israel Lund and Amy Granat. Granat and Lund are masters of the slight gesture expanding to envelope the viewer in perceived meanings and implications, but the works in this exhibition are especially attendant to the realm of perception. Like the rods and cones in one’s retina reacting to various wavelengths of light, the viewer reacts almost entirely to what they think they see as opposed to anything that is intentionally there. One could spend a very long time squinting at the flickering dots and blotches of ILDH (2017) a loop of film projected onto a ghostly white rectangle painted onto plexi, attempting to pinpoint the origin of this footage. The surface of the moon? Bacterial colonies? But this questioning presupposes an origin to the film. On closer inspection, Granat has spray-painted white paint onto celluloid, circumventing the entire history of photography and replacing it with pure and simple abstraction. “Two wrongs make a right,” or “two rights make a wrong,” or something along those lines: white spray on clear film plus white paint on plexiglass plus a light source results in black, concrete, and distinct form with the implication of narrative through movement in time. It’s a working definition of film and the answer to a neoplatonic riddle, with a soundtrack of pounding static and the whirr of the endless loop of the projector.

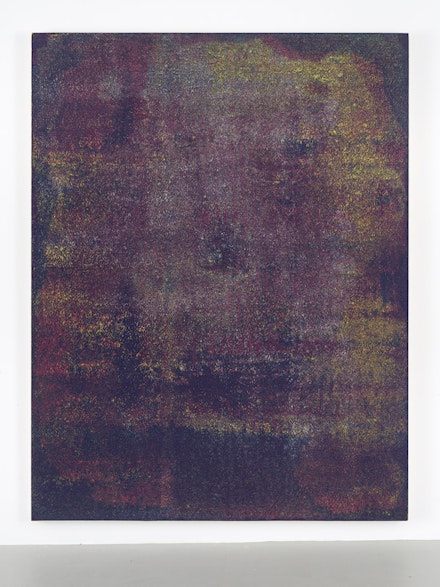

Meanwhile, Israel Lund approaches a similarly abstract miasma of fuzzy perception through forms that appear generated by radar or sonar. Dots of data are conjured up, in this case via the artist’s distinctive methodology of laying down the main colors of printing; yellow, magenta and cyan, in the form of screen-printing ink, activating different wavelengths on the color spectrum based on how they adhere to the warp and weft of raw canvas. In Untitled [IL040] (2017), there is depth, phantom image, and topography in the vibrant greens blues and scarlets, while shimmering yellow implies some kind of mysterious form such as in an ultrasound or a purported trace of the Loch Ness Monster. Lund’s aesthetic harnesses the random by meticulously preparing to unleash the unexpected results of his creative processes. These pieces hearken back to the work of the lyrical abstractionists of the ‘60s and ‘70s, such as the iridescent folds Ken Showell, the early stain paintings of Ronnie Landfield, or dot paintings of Peter Young. Lund enjoys playing with his method, experimenting with reversing the order of his colors, which yields a fiery block of oranges, ochres and yellows, a delightful oversaturation in Untitled [IL039] (2017), or purposefully blanking out a large region of the cartography of his painting in Untitled [IL042] (2017), leaving the viewer wondering if something is somehow blocking the scan or corrupting the data.

Granat and Lund don’t completely shy away from the image. Two token works in the exhibition; Ripple (2017) by Granat and Untitled (Severed Head) (2017) by Lund, both move beyond conjecture and implication into actual representation. Though embracing the CMYK palette of his other paintings, Severed Head is unequivocally factual. A slight subtext of horror is added by recent events in the Middle East—a grotesque reality beyond the art historical iconography of a severed head—but despite the shimmering and flickering pixels, the image is the image and it is static. Granat’s technique in Ripple, which is strongly aligned with her machinery in ILDH, manages to overwhelm her imagery with the same uncertainty principle of the aforementioned piece, despite the fact that we are aware that we are looking at a specific something or somewhere. Fragments of urban fabric are double exposed over what seems to be the whimsical architecture of Félix Candela, and these undulating and geometrical forms are distinctly buildings, with people interacting. This raises questions of place and purpose. As the images are washed out to a blank whiteness, we become uncomfortably aware of the blinding light of the projector, and the suspension of disbelief crumbles as we blink and squint. The materiality of the art overtakes what it is representing. It’s an entertaining dyad of representation versus the means of representing, set up almost as a sort of confidence trick that lures you in via your curiosity about something as banal as subject and then jabs you with the medium, punishing you for trusting your eyes.