Peugeot Taipan, Commemorative Model (Discontinued Line) 1999, PVC piping, PVC sheeting, Milliput, airbrushed stone-white automotive paint (Art Gallery of Western Australia collection, Perth)

Ricky Swallow’s intensive labours honour some private incidental moments, to which end all the modelling, building, and carving can seem simply autobiographical. A telescope – handcrafted and built to scale in moulded PVC plastic – is an exact replica of one from his childhood. Using cardboard, PVC, timber, or bronze, Swallow has also built other “commemorative models” (as he has described them): a replica of his BMX bike, his radio cassette player, the family’s metal detector, a favourite pair of shoes, Caroma stools from the rumpus room.

Vacated Campers 2000, binders board, paper, glue (Suzie Mellhop and Darren Knight collection, Sydney)

But it’s not simply personal, since the passing of these worldly goods and scenes reflects our own passing, too, and more fundamental shifts besides. A model of the family telescope might also mark the obsolescence of optical technology because of new digital means. Indeed, all Swallow’s models evince subtle signs of changing times, fashions, styles, and techniques, in short, the mortality of a generation, if not an entire species, on the brink of extinction, which explains Swallow’s fascination for future scenarios that have already come to pass.

Swallow asks, after Planet of the Apes, when the art museums are excavated in hundreds of years’ time, what will indicate the common values of contemporary culture? In answering, he finds special significance in his own experiences: a Gameboy encrusted with carbuncles from the great flood; Darth Vader unearthed from shifting sands like some great lost pyramid; the National Gallery of Victoria in ruins, uncovered from jungle. In each of these scenarios Swallow rediscovers his own culture in the future, its current significance redoubled in its imagined obsolescence.

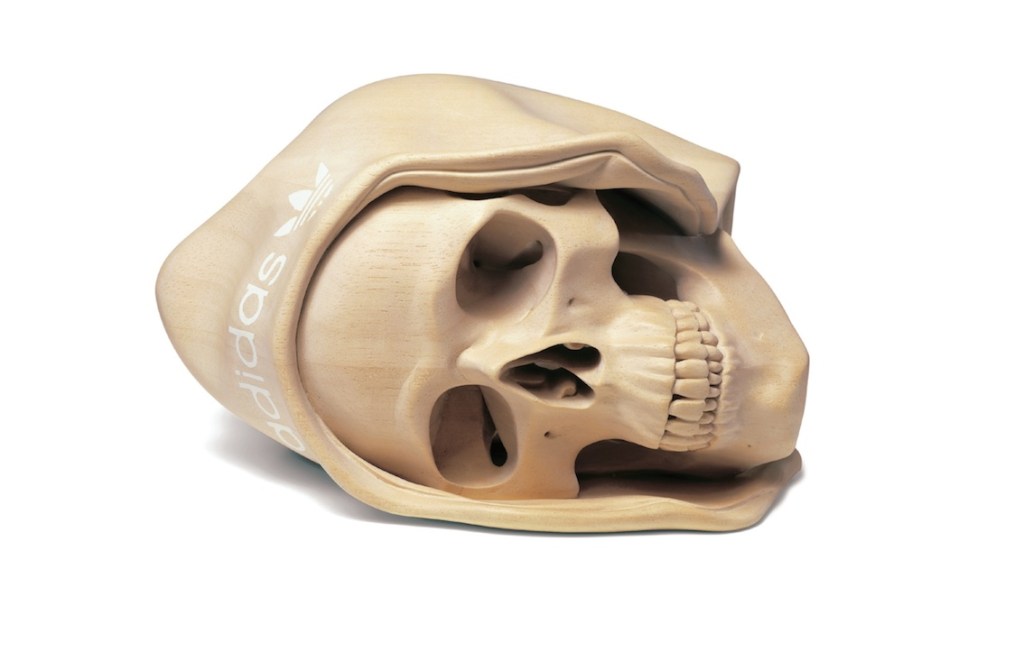

Swallow has used more traditional means and materials, too, carving hardwoods such as jelutong and English lime. The objects – a sleeping bag, streetwear, a beanbag, other signs of a modern leisurely life – are not simply copied as before but mixed with other elements, producing surreal, deathly collages that convey our mortal predicament obliquely through poetic symbolism. A bird nests in an empty shoe, a fish lies within a car tyre, a skull sinks softly into a bean bag or nestles cosily into a jacket hood, a snake writhes entangled within a bike helmet, a pair of gym boots has been caught by its laces in the branches of a dead tree. In the vanitas tradition, death lurks in such vacated nooks and crannies, in all our beloved earthly goods.

The symbolism is more generic in two large-scale still-lifes – one representing all the seafood that Swallow, the son of a fisherman, has caught and killed spread across his family’s kitchen table, the other, a composite study of hanging dead animals copied from various historical paintings. These works combine motifs from Swallow’s personal life with conventional art-historical formats, techniques, and subject matter (say, Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin or Gianlorenzo Bernini). The combination suggests the personal origins of genre (by which we might compare our own consumer interests in Camper shoes or iMacs to those excessive still lifes commissioned by the Dutch middle-classes in the seventeenth century). It also suggests the generic art-historical relevance of one’s own life (by which we might compare viewing The Ecstasy of St Theresa in the seventeenth century to nostalgia or commodity fetishism today).

Killing Time 2003–4, laminated jelutong, maple (Art Gallery of New South Wales collection, Sydney)

Swallow’s comparative method is most explicit in the pairing of bronze sculptures of Mary Magdalen and 1960s singer-songwriter John Phillips, two emaciated figures side by side atop timber plinths. Swallow follows Donatello’s sculpture of a penitent Mary and the cover art of Phillips’s first solo album, recorded at the height of his drug addiction. The work seems to ask whether dissipated rock stars – who ‘spoke for a generation’ – shouldn’t be among our long list of martyrs and who the historical precedents are for today’s icons. Remember, Mary is already a heroine to the Gnostics and the Catholics. Bronze simply redoubles the question.

Swallow’s precise, considered choice and his dedication in rendering these select elegiac moments and objects within some of the grand craft traditions is, as he says, “a matter of pulling things in and out of time, passing objects through the studio”. There’s a strange hiatus in time and space on top of these plinths that enables the direct comparison of things, and lives, from around the world and years apart – the proper measurement and calibration of epochs, which ensures our current common interests are candidate for the grander classifications.

Courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney; and Stuart Shave Modern Art, London.