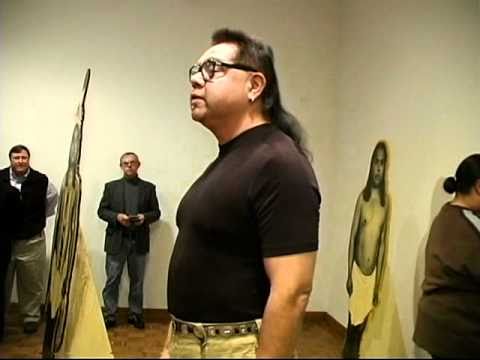

James Luna (photograph by Jason S. Ordaz, courtesy IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts)

SAN DIEGO — The internationally-known performance artist James Luna was laid to rest on March 17, in a simple but powerful funeral service on the La Jolla Indian Reservation, in the mountains above San Diego, California.

Luna, who was of Luiseño, Ipai, and Mexican descent, lived on his family’s land for most of the last 25 years. His burial was attended by well over 150 people, including tribal members, family, friends, and colleagues, many of whom had done art shows with him or had curated his work.

As the clouds curled over the mountains above, mourners stood under a slight drizzle in the crisp air, listening to a series of speakers remember an artist whose work inspired others with its willingness to challenge conventional attitudes about Native Americans.

Speaker after speaker spoke of Luna’s fearlessness as an artist, his love of wordplay and incisive wit. At the end of the open casket service, people patiently lined up to pay their respects. What stood out was “how human it was,” said Patricio Chavez, a photographer and college instructor. “James was beloved by so many.”

Luna’s unexpected passing at the age of 68, during a residency in New Orleans, interrupted a steady — and some would say brilliant and provocative — flow of performances, photography, and other art that dove into the space between Native and American. Luna lent his name, his voice, and his body to Native art and identity.

“James Luna is one of the most important contemporary Native artists of our day,” said Patsy Phillips, director of IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, in a statement to Hyperallergic. “His art and contributions to the art world will live on in institutions and publications, but more importantly he will live on in perpetuity in people’s minds and hearts.”

Luna’s work was some of the first to bring California Indians, a group largely absent in discussions of Native American art and culture, to the artistic fore. Luna tore down “the boundaries of imposed perceptions and limitations on the expression of what it is to Native American today,” said Mario Chacon, a prominent local painter and college instructor who regarded Luna as his spiritual brother.

Many at the funeral remembered what Luna considered one of his most significant works, “The Artifact Piece,” performed at the San Diego Museum of Man (1987) and The Decade Show at the Museum of Harlem in New York (1991). “It was a really important work, but James had not anticipated how hard it would be,” said Alessandra Moctezuma, an artist and curator of the Mesa College Art Gallery.

Luna’s piece involved laying in an exhibit case, surrounded by the artifacts of his daily life. Each object, as well as his body, was carefully labeled. “Outrageous and brilliant, ‘The Artifact Piece’ rumbled across Indian Country in the late 1980s like a quiet earthquake, making fine work by other Native artists suddenly look obsolete and timid,” Paul Chaat Smith, Associate Curator of the National Museum of the American Indian, wrote of the performance.

Luna was surprised, Smith has said, at how many people touched him, thinking he was just another object. Visitors were equally surprised to find out that Luna was alive and well. In Smith’s view, Luna took Native Americans, and especially California Indians, out of the rarified world of the museum.

“James has a fearlessness and a willingness to use his body — the body politic,” said Chavez, who is also a former visual arts curator at the Centro Cultural de la Raza. Luna was a driving force in one of the most creative times for the Centro, he added.

Luna’s later work included the performance “Take a Picture With an Indian,” one of the centerpieces of the documentary Race Is The Place by Rick Tejada-Flores and Ray Tellez. In the segment, Luna stands in “Native dress” in San Francisco’s Union Square, inviting people to take a picture with him. “America likes our arts and crafts, Americas like the romance. America doesn’t like the truth,” says Luna to the crowd watching him.

The closing ceremony of Interwoven: Indigenous Contemporary at the University of San Francisco’s Thacher Gallery (via Thacher Gallery on Flickr)

In another work, “I CON” (2014), Luna deconstructed the romanticized story of Ishi, the last Yahi Indian, and the mythology contained in dusty museum cases. “It was a powerful statement about the colonial notion that Native Americans are in museums to study — but are real human beings,” said Moctezuma. Luna gained attention both nationally and internationally, and was featured in the 2005 Venice Biennale. In 2017, he received the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for exceptional creativity in the arts.

Photographs of Ishi and Luna as part of the installation “I CON” (courtesy Alessandra Moctezuma/Mesa College Art Gallery)

He styled himself as America’s “most dangerous Indian,” challenging viewers as he went. In later work, Luna questioned the usefulness of measuring bloodlines and, in both lectures and performances, criticized romantic narratives of Native California with candor and humor on stage. “He did it with a way of disarming people, while being right on in his critique,” said Chavez.

Luna’s untimely death has left a huge hole in the La Jolla Reservation community, and the arts community as a whole. “I will miss him, but in a palpable way,” Chacon said. “He lives within me.” When Luna’s coffin was lowered, the drizzle stopped. The sun broke out over the mountains, brightening the meadow and the mountains that Luna loved.

James Luna (photograph by Jason S. Ordaz, courtesy IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts)

It is a pitty you died so young, you could do so much more! I met you in Santa Fe in 1992 and you related some of your future works. I invited you in Greece to show, but you told me there was no point showing so far away from home – you thought who would care in Greece about red indian art! Rest in peace artist warrior!