Betye Saar

by Jonathan Griffin

Betye Saar has lived in the same shingle-clad house up a winding lane in Laurel Canyon for nearly 60 years. To reach the front door, on the house’s top story, visitors ascend several flights of steps, passing the kind of thickly planted garden—filled with ornaments and trinkets—that can only be created with decades of care and cultivation.

Saar moved to Laurel Canyon with her former husband, Richard, and three daughters in the early 1960s, shortly before the Hollywood Hills became the nexus of Los Angeles’ hippie music scene. Frank Zappa lived in a log cabin just a few doors down, and Neil Young, Brian Wilson, and Joni Mitchell were also neighbors. The Saars were a hip, artistic family: Betye was a printmaker and designer, and Richard a ceramicist and art conservator. They led a comfortable middle-class life but were far from famous. As with most Black artists of her generation—and virtually all female artists—Saar made her way outside of what little limelight shone on the local art scene. For years, she didn’t even consider herself a real artist.

Today, Saar is close to what the Japanese call “a national living treasure.” In 2019, she was honored at LACMA’s annual gala. This spring, before Covid-19 brought the world to a halt, she was due to receive the Wolfgang Hahn Prize, Germany’s highest artistic accolade. When I caught up with her over the phone in March, a couple of weeks into her self-isolation and having canceled her travel plans, she laughed that she was relieved to finally be able to stay home and make her art.

The past few years have been among the busiest of Saar’s long career. I first met her in 2016, just as she was looking forward to the opening of a prestigious survey at Milan’s Fondazione Prada. At home, Southern California’s art narrative had also expanded beyond the mainly white male heroes of the Ferus Gallery and the Light and Space movement, so Saar received renewed attention for her sculptures and prints.

Quick to laugh, Saar has an ever-present glint in her eye, her curly silver hair pulled up by a head-scarf. Her walls are closely hung with art by friends and family, old and new. She particularly favors self-taught artists—“There’s a kind of innocence to their work,” she says. A stair lift descends into her double-height home studio, where birdcages, clocks, and model ships are lined up on shelves, and half-finished sculptures are laid out on tables. Another crowded sculpture studio takes up the converted garage below, but these days she finds working upstairs warmer, more comfortable.

Saar combines found objects with her own drawings, collages, and prints to make assemblages in the tradition of Robert Rauschenberg or Joseph Cornell. She is a collector and a scavenger, picking up bric-a-brac at flea markets and antiques stores, and incorporating it along with consumer products and animal bits, including feathers, bones, and horns. Sometimes she introduces images, such as the famous 1787 diagram of the Brookes slave ship. Many of her sculptures resemble Americanized versions of ritual African artifacts; a student of palmistry and mystical belief systems, Saar believes that spirits inhere in objects, and that certain combinations of materials can exert a supernatural power.

Saar’s parents came to California in the early 1900s. Her part Irish-American, part African-American mother was from Iowa by way of Kansas City, and her African-American father from Lake Charles, Louisiana. They met in the 1920s as students at UCLA, which few Black people attended back then. When she was five years old, Saar’s father died, and her mother took her and her siblings to live with Saar’s great-aunt Hattie in Watts, the predominantly African-American neighborhood in south Los Angeles. It changed Saar’s outlook forever.

She remembers walking along the train tracks in Watts, passing beside the magnificent towers of concrete, rebar, and pottery shards slowly rising in the garden of an eccentric Italian immigrant named Simon Rodia. The Watts Towers were not completed until 1954, when Rodia abruptly left the city. He did not consider himself an artist any more than Saar’s mother, great-aunt, or grandmother considered themselves artists, despite the multitude of things they made: decorative needlework, lace, quilts, clothes, not to mention their cooking and other forms of home-making.

“I think, for me, creativity has just always been there,” Saar told me. “Even as a little kid, probably three or four years old, I knew what colors I liked and what colors I didn’t like.” At that age, she also believed she had clairvoyant abilities. She had an imaginary friend named Rosie, who she remains convinced was a ghost. Those gifts left her when she was five, perhaps in response to losing her father, but she has never lost what she calls her “mother wit.” It is this second sight that she relies on when deciding what to put into and what to leave out.

When Saar applied to college in the 1940s, her choices were limited. While universities were not officially segregated in California, Black people simply did not apply for fine-art courses, nor would they likely be accepted. Instead, Saar studied design, specializing in interiors, which, she stresses, was not the glamorous career it is now. Before her graduate studies in the late 1950s, she worked as a social worker, and during this time she took a print-making elective that offered her a pathway into art.

In 1952, Betye married the ceramicist Richard Saar, who was white. Together they sold their wares through invitational exhibitions and, in the 1960s, even Renaissance fairs. Their first daughter, Lezley, was born in 1953, then Alison in 1956, and Tracye in 1961. (Lezley and Alison are now both artists, and Tracye is a writer.)

The couple divorced in 1968. It was also a tumultuous time politically. The Watts Riots of 1965 had torn apart the neighborhood. In 1968, Martin Luther King was murdered in broad daylight, a blow that left the civil rights movement reeling—and, Saar told me, “was something I really reacted to in anger.” She was coming to see herself not as a craftsperson, but as a fine artist—one who had much to say about race and about feminism.

In 1967, she had seen an exhibition by the self-taught artist Joseph Cornell that impressed her deeply. By combining pieces of discarded objects and old photographs in entrancing shadow boxes, Cornell showed Saar how she might use “the flotsam and jetsam” she had gathered over the years to make work that was not only about her own personal experience, but also about those of others like her, and about the historical legacy of slavery, imperialism, and misogyny that they shared.

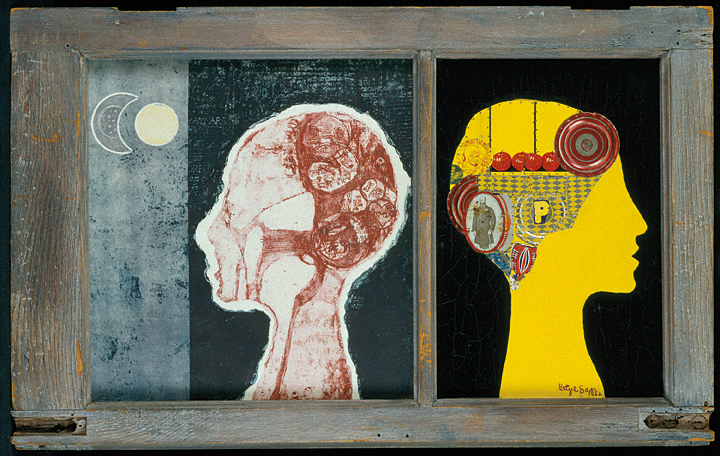

Perhaps her most famous piece is Black Girl’s Window (1969), which is now in the collection of New York’s MoMA, where it was the focus of a 2019 exhibition. It is a transitional work that integrated various aspects of Saar’s practice and vision: printed images taken from tarot, astrology, and phrenology; a daguerreotype of Saar’s grandmother; a cartoon illustration of two Black children embracing. She fitted it all into the small panels of an old window frame she’d found. Painted on the inside of the glass is a picture of a black-skinned woman. Saar has referred to the work as a self-portrait—“my mystic self is pressing against the glass, the window of the unknown.”

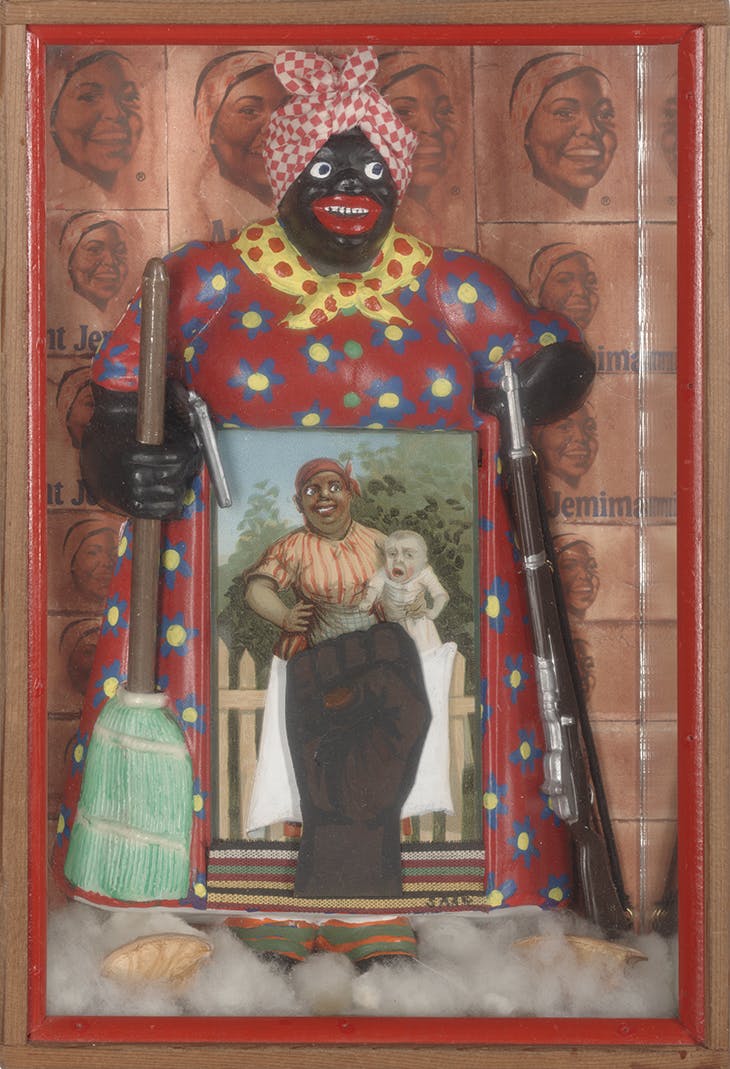

In the wake of King’s murder, Saar became increasingly political. Responding in 1972 to an open invitation by a gallery in Oakland—“Black Panther territory,” she notes—Saar submitted a sculpture based on a figurine of a stereotypical Black housemaid, but holding a broom in one hand and a rifle in the other. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima was the first of many sculptures that incorporated examples of racist imagery, redirecting its negative energy into a defiant, assertive message.

I ask Saar if there’s anything she would not include in a sculpture. “I imagine a rope used in a lynching would be too negative,” she answers. But, she notes, she has used photographs of lynchings— as in the 1972 wall assemblage Let Me Entertain You, which contrasts an illustration of a Black banjo player with a rifle-toting Afroed revolutionary against a Pan-African flag. The 1930 photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, a gleeful mob gathered around their feet, is included in the center: a bridge from the submissive entertainer to the armed revolutionary.

“I’m not a person who holds onto anger,” Saar says. “Making art was part of the relief from it. That was my therapy.” Over the next decades, her focus shifted from the injustices of contemporary America to the interior lives of African diasporic cultures displaced by slavery. In 1974, she used part of an NEA grant to travel to Haiti and study the Vodou practices that had come to the Caribbean with West African slaves.

Saar learned about African ritual and talismanic objects, in which materials such as shells, bones, or wood are combined to generate a supernatural force. The process, she observed, was analogous to the way she works. “Mojo” is a term from African-American Hoodoo magic usually referring to a small bag of charm objects gathered to make a spell; Mojo Bag #1 Hand (1970) is an early example inspired by this, as well as by Native American medicine pouches. Painted on cowhide is a hand with an eye in its palm—a recurring motif in Saar’s work, an interpretation of the amulets found throughout the Middle East and North Africa that are intended to protect the bearer.

Has Saar’s work protected her, I wonder? “Oh yes,” she answers. “It’s the creative energy that comes from doing my work that’s really positive for me. Once it goes out from my studio, whether it goes to a gallery, sale, or museum, the positive energy that I had when I was creating it goes with it. I think that’s why I get such a positive response to my artworks—because people somehow feel that.”

When, in the 1980s, Saar was invited to a residency at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she created one of her largest installations: Mojotech (1987), an arrangement of panels organized around a central altar, on which visitors were invited to leave “personal or technological offerings.” Elsewhere, computer parts, circuit boards, and mysterious electronic devices were contrasted with more traditional arcana such as candles, snakeskin, bones, and mirrors. In Mojotech, two kinds of faith rub up against each other: belief in the unseen capabilities of technology, and belief in the ineffable power of the occult. Both are thought by their adherents to be limitless.

A few days before I spoke with Betye, I received an email from her. This was just after Donald Trump declared a national health emergency to contain the spread of Covid-19. The email’s upbeat subject line was “Safe Spring Greetings!” and it contained a single painted image: against a coral-colored background was a raised hand with the word “Hi” painted simply in its palm. “Thinking of you, stay well,” Saar had added in her looping script across the top of the picture.

Saar told me she had sent the email to everyone on her mailing list. “That’s the only thing I’ve done in response to the outbreak of this virus. I wanted everyone to know that I’m alive and thinking of them in a positive way.” Having done that, she felt she could move on and put it behind her. “I’m not really reinforcing negative things by making art about them.”

Saar is 93, but she reprimands me when I ask how age has changed her perspective. “I don’t like to think of myself as old.” She concedes that, physically, there are tasks for which she now needs to enlist the help of a studio assistant, but she maintains, “As long as there’s an idea in my brain, I can still keep doing it.”

“This is one thing I tell anyone who’s interested in the arts,” she continues. “Creativity gives you new life. I can’t think what I would do if I didn’t have my drawing and my art.”

First published: BLAU International, No. 2