Published in The Peak, October 2017

“Computer users know that the best way to optimise your system is to ‘empty’ and ‘reboot’.” This is the message that is fixed upon the wall at White Cube gallery and greets visitors to Rotation. The exhibition is Chinese artist Wang Gongxin’s first in Hong Kong and brings together a body of his work from the 1990s alongside newer pieces created for the show – 11 in total. Rotation is a process of revisiting and ‘rebooting’ twenty years of artistic practice for Wang, a coming back to earlier installation works.

Born in 1960, Wang is a pioneering multimedia artist, the first in China to incorporate video installation into his oeuvre. However, he began his art career as an oil painter. Amid the first generation of art students to emerge after the Cultural Revolution, Wang trained in the prescribed socialist realist style that trickled down from the Soviet Union. It was only in 1988, while a visiting scholar on a cultural exchange programme at State University of New York at Cortland with his artist wife Lin Tianmiao, that Wang first encountered video work. While he continued painting portraits to earn a living during his year in the States, this encounter with video work by artists such as Bruce Naumann, Bill Viola, and Nam June Paik had left an indelible imprint on him. Two years after returning to Beijing, Wang became a catalysing force of the Beijing avant-garde movement, turning his home into a salon gallery space where artists could meet and show their work.

At this point the artist left painting behind altogether, creating his first video project, ‘The Sky of Brooklyn—Digging a Hole in Beijing’ in 1995. Video offered a break from the constraints of the formal and strict training he had received at school in Beijing. It offered freedom, a clean slate, and creative possibilities. “It allows for more information to be brought to the work,” Wang says. “It encompasses everything – sound, light, movement – [and] it allows you to tell a more full story.” In 2001, he would go on to found Loft, one of the first media art centres in China.

The site-specific ‘The Sky of Brooklyn’ was a catalysing work, setting the tone for a practice that became defined both by experimentalism and humour, exploring the relationship and balance between materiality, temporality and space. The artist dug a 3.5-metre-deep hole in the gallery floor in Beijing and placed inside it a video monitor playing footage of the Brooklyn sky, shot from the roof of his Williamsburg apartment. Visitors could peer into the hole with the illusion of looking through to the other side of the world. The work was a tongue in cheek reference to the expression “digging a hole to China”, but it also revealed Wang ’s personal encounter with the cultural and political disparity between the two places; an examination of the geographical and cultural dislocation he experienced living in New York and then returning once more to Beijing. The piece was acclaimed by CNN as one of the “10 artworks that will change the way you see China”. Today, the artist has been commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum in New York to create a counterpart piece to the work, redirected this time towards China, as much of the world’s attention is.

Wang broadened his artistic language beyond video. Early on in his career he began experimenting with incorporating materials in his installations that were mobile, “radiant” and liquid. Materials like light bulbs, water and metal that reacted to and played with the environment around them through reflection and movement were often combined in his works. The exhibition at White Cube features these ready-made installations full of kinesis and light, which reveal a preoccupation with time, memory and space.

Take Wang’s 1995 installation, ‘Dialogue’. In a darkened exhibition room, two suspended light bulbs descend into a pool of black ink on a long black table. Each time the bulbs dip into the liquid, ripples are created on the dark, still and reflective surface of the water, breaking the seemingly rigid geometry and solidity of the work. Shadows play across the walls, activating the space. The installation – as its name implies – encourages a dialogue between viewer and work, between materials (ink water and light bulb), and reality and imagination. A reverent hush falls over the space as visitors stand before the work. “Everywhere I have showed this work people are always quiet in the room standing before it”, the artist comments. Indeed, there is something particularly zen about standing in the darkened room – the work invites contemplation and meditation. It is oddly hypnotic in its repetitive and rhythmic movements and in its minimalist monochrome.

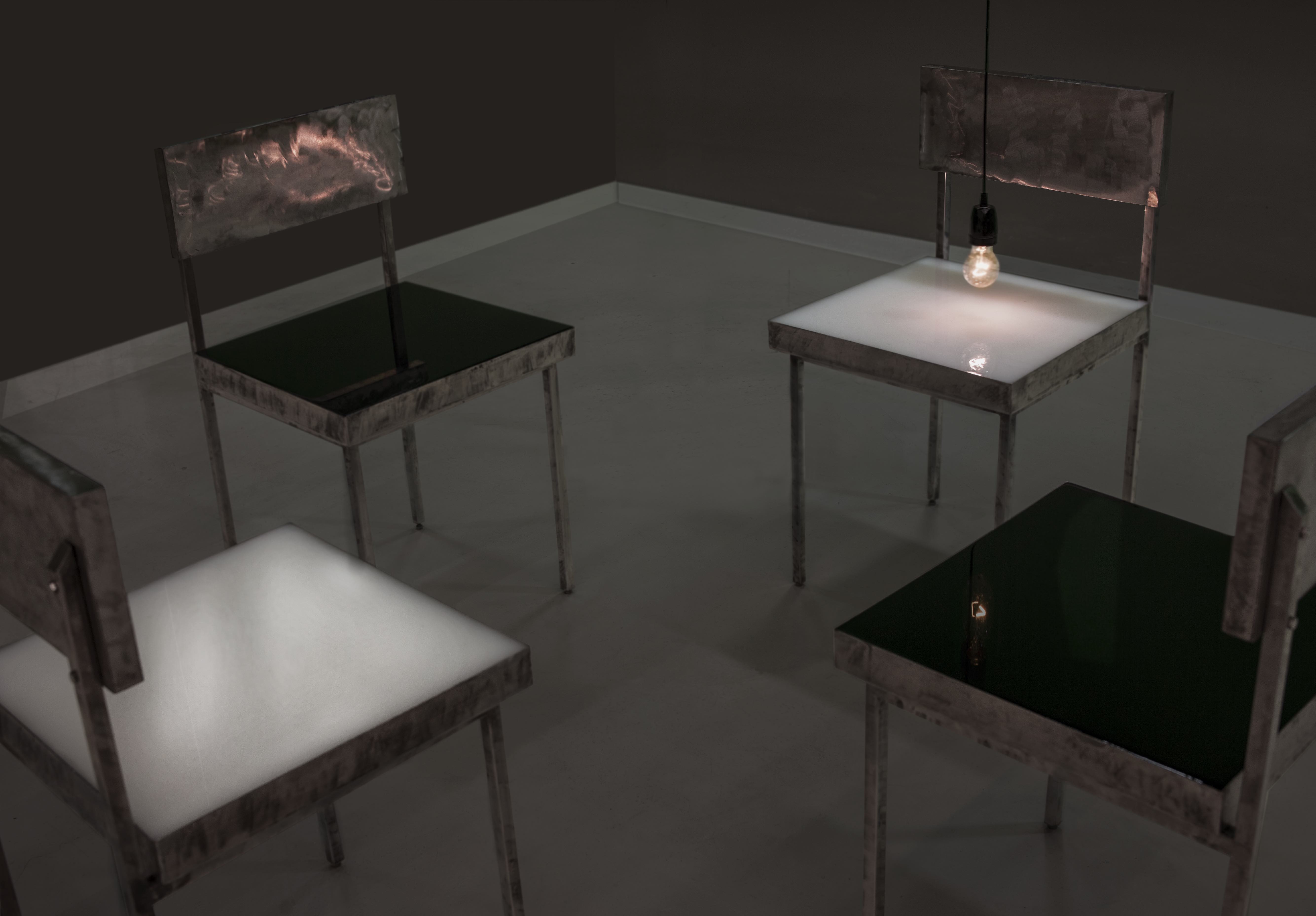

Wang works with a repertoire of materials, gestures and mechanical movements for his installations, highlighting a concern with temporality. The knocks, ripples, dipping and rotating of the light bulbs take place in a rhythmic and repetitive manner. In ‘Unseatable’ (1995), which features four metal-framed chairs – each seat filled with either a milky white liquid or a black ink – a light bulb suspended from the ceiling rotates over each chair, its light re ected back by the even, liquid surface of the chairs. Like in ‘Dialogue’, the second instalment of this piece, this repetition of movement is a marker of time comparable to the even, predictable ticking of a clock. Yet at the same time, these works are heavy with quiet tension and danger. ‘Dialogue’ skirts with the danger of electrocution or exploding glass if the light bulbs are immersed too deeply in the liquid, and the danger that the dipping light bulbs will unsettle the equilibrium in the volume of the liquid, sending it spilling over the sides and onto the floor. The work plays with limitations and boundaries, experimenting with how far one can possibly go before equilibrium is lost. The artist had to carefully calibrate the volume of water to ensure that it sat at the very edge of the container, yet would not flow over the top.

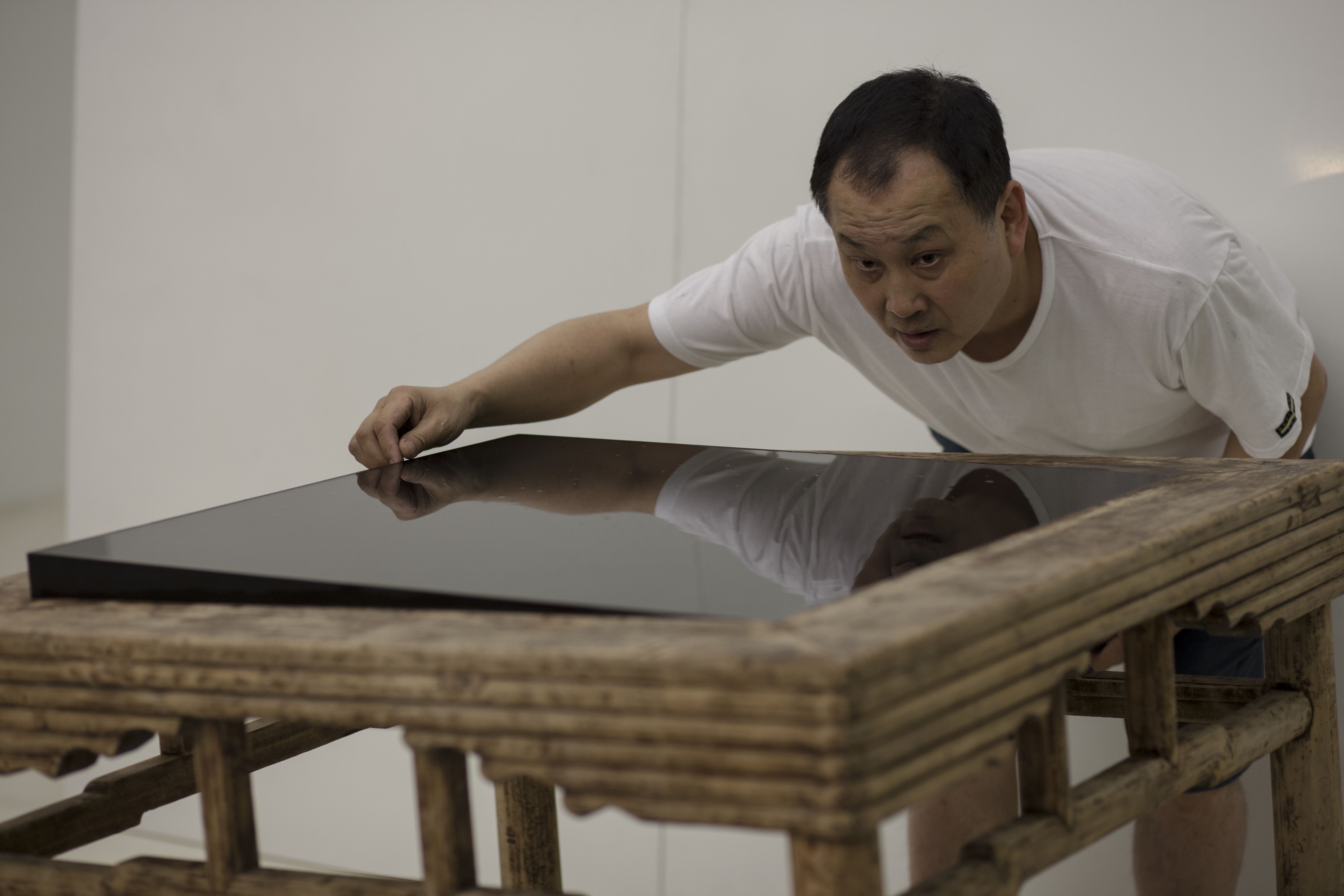

Restoring balance is a recurring theme throughout this exhibition, although it was never something that Wang set out consciously to explore in his work. It was, he insists, a theme that revealed itself as he progressed in his practice, with possible antecedents in his training as a painter. “Yes, it’s almost like painting. You know when it’s there and when it isn’t,” he says. “You know when you have a balance of composition and colour.”A more recent work, ‘Horizontal’ (2017) features a square Ming- dynasty table, with one leg shorter than the others and propped up on a golden stone to even it out. On top, a tray filled with black liquid juts out at an angle, evening out the slanted surface of the table. A mechanism underneath knocks the table and sets the water into ripples, bringing what was a static object to life.

Despite the striving for aesthetic balance in the works, there is an element of the unheimlich about Wang’s installations. An unsettling and anxious feeling results from watching a table vibrate and the water ripple, repetitively and compulsively, from an unknown ghostly source, or a light bulb dipping inexplicably in and out of wooden bench or a pool of black ink. Tables, chairs, a baby’s crib – familiar objects that are indispensible to our everyday life, objects that are part of ones rituals, routines and personal narratives – are reappropriated and incorporated into wholly strange and unfamiliar contexts.

Just as Marcel Duchamp had once taken a simple bicycle wheel or urinal and turned them into works of art, Wang too subverts reality, and confounds and challenges viewer expectation by re-contextualising humble everyday objects and stripping them of their original utilitarian purpose. He takes the ordinary, the banal, and transforms them into playful, at times immersive, visual poems.

Leave a comment