«Distance is not a safety zone but a field of tension.»

Georges Didi-Huberman underscores and enhances this quotation taken from Adorno by adding that «each seen thing deposits us before a field of tension or, rather, multiple fields of tension, which can either be psychological or logical, sensorial or gnoseological, memory-related or desiring».(1)

The concept field of tension applies in a specifically precise way to the snapshots of Nazi soldiers in drag that Martin Dammann collects in this book. They set upon our eyes the request of resorting to an unaccustomed gaze, quite different to the one habitually cast on old snapshots (those survivors protected by Chance: the sole remains of days that once were or timeless images quirkily storing hidden matter of reality), and which turns utterly literal the idea that tension can led to the outbreak of conflict. The eye can cause here an upheaval in the conscience.

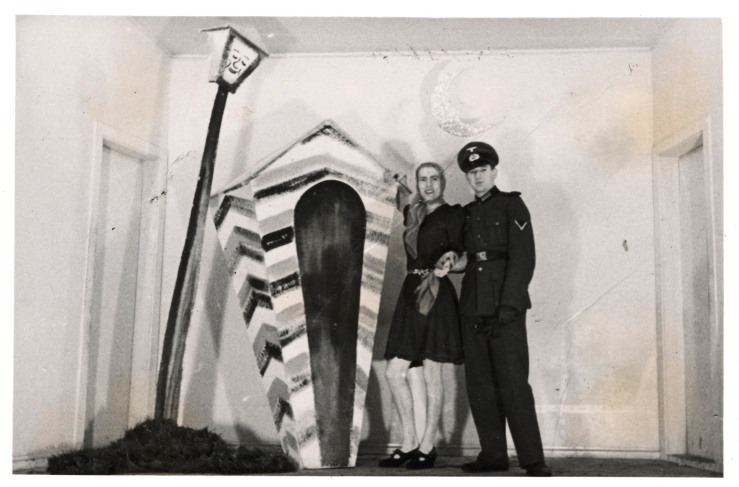

A terrible war was happening and millions of people were locked and sentenced to death in Hell and here, in these images taken in the meantime, we see men clumsily dressed up as chorus girls entertaining their military uniformed audience, good-looking guys playing the beautiful sensual diva, men posing as respectable ladies or as frumpy small-town girls or strutting in a suspender belt and stockings, two amateur actors in a lustful embrace (one is dressed up as a sailor, the other one as some languid odalisque), young men wearing bras and miniskirts on a day by the sea or flaunting their gowns at the village’s dance.

How did you become interested in collecting these snapshots portraying Wehrmacht soldiers in drag?

My interest started a long time ago, in a flea market in New York where I found by chance some small soldier snapshots and I realised how much more detail there was compared with photos published in history books.

My search intensified a lot during the late 90’s, when I spent a year in London with a DAAD grant (a German exchange programme for students). While I was there I got in touch with the Archive of Modern Conflict, a private archive specialized in photos taken by soldiers. We got on very well and finally they asked me if I would like to buy soldier albums for them.

So I started seeing countless soldiers’ albums, from all countries, all conflicts that ever have been photographed. After a while I came across the photo of a cross-dresser, a guy in a short white skirt on a makeshift stage with a big swastika in the background. At first it looked like just one crazy photo. Of course, I took it, but only when more photos of soldiers in drag kept appearing I began to understand that it was not just an exception, that this must have been a common habit among soldiers. Even then it took me a little while before I realised what significance it had.

The fact you came across those snapshots at that flea market is telling you were somehow already interested in snapshots as visual documents?

Yes, I have always been very interested in all kinds of vernacular photography: photos made by untrained photographers, where the message is very different from the ones that are taken professionally. The private ones are often difficult to categorize, they are more ambiguous and often a lot more surprising.

I remember the book being given wide media coverage in Spain. The information about its release used to be accompanied by a selection of the images included in it. My feeling was that the subject made extremely interesting news because it was indeed fascinatingly shocking to see these playful, sometimes even highly homoerotic, images of Nazi soldiers in fake bras and striking sexy poses, wearing wigs and make up and cuddling up affectionately to their comrades in uniform – undoubtedly because of all the well-established general connotations associated with the Nazi ideology, history, imagery and psychology. However, and precisely because of that, in addition to the fact that you are an artist yourself, I wondered if, apart from collecting these documents to build this side of the visual history of the Second World War, you were actually intending to challenge and unsettle the viewer’s perception.

I am an artist and as such I am interested in all sorts of “problem zones” of society and individuals: when things become, as you say, unsettling. Hidden, surprising matters might show up, sometimes things unseen before.

Were you struck by the amount of material that you kept finding?

Photos of soldiers in drag are not on the common side. Still, over a period of fifteen years, I ended up with about 300 of them. It looks like cross-dressing reflects a kind of basic experience of soldiers in wars, not only for the Germans, not only in World War II: Soldiers, far away from home, within a hostile environment and uncertain future inevitably come to longing for what they have left behind. To “reproduce” the missing beloved ones seems an easy solution, at least for a moment.

Yes, one of the possible interpretations they offer is looking at them as an expression of heimweh, the longing for the joy of times of peace and the affection and company of women. From this perspective, these pictures appear as captures of the most human side of people.

Then, seen from another perspective, what we see in these pictures is men posing as an ersatz of women within a context structured according to a pattern of male heterosexuality, and this raises another type of questions.

The female fantasy constructed by cross-dressing men in the Wehrmacht portrayed in these snapshots seemed to be mostly divided between the demure stay-at-home National Socialist ideal woman (meant to be a wife, a mother…) and the glamorous Hollywood-vamp or chorus girl type.

That was a surprise; the soldiers did not only impersonate their societies´ ideal women, or pin-up clichés. They re-enacted all kinds of women, also the ordinary housewife, marriages, dominant women, even the grumpy grandma might appear.

The habit of cross-dressing amongst soldiers stretches across all nationalities and conflicts. Yet there is an especially high percentage in albums of German soldiers of World War II. This also was a surprise. It does not necessarily mean that the Germans performed it more than others, but they certainly photographed it more.

Several things might come into play: first, German soldiers were obsessed with cameras. Then, in Germany, unlike in the English-speaking countries, there was a tradition of dressing up in Carnival time; therefore, it was easier to camouflage the true feelings behind the conventional habits of Carnival. Service time of German soldiers was very long and it brought them to places they would never ever have expected to come. That certainly fostered their desires and longings.

And it might well be that the hyper-masculine ideal that the Nazis imposed did put an additional pressure on the men, which, as a consequence, created the need for escaping or balancing it – through the exact opposite. For example, just a few weeks ago, I discovered a telling album page: in the top left corner you see a photo with two young soldiers posing half-naked, boasting their muscles and chests in a way that reminds of the works of Nazi sculptor Arno Breker; then, in the lower right corner you see the same two soldiers dressed up as women. The complete opposite on the very same occasion. What might appear as a contradiction is likely to be a reaction.

Many of the images seem to capture an instant from a mise-en scène. It is not something uncommon in old snapshots: people used to make funny poses or improvise theatrical scenes to have their picture taken.

Some of the snapshots included in the book were taken during actual theatre performances made to entertain the troops; however, in many other ones we get the impression that we are looking at an instant out of some playful fiction being performed as ‘reality’ – a fantasy that seems to act as some kind of compensation (something that would connect with your remark above). Both the men dressed in uniform and the men in drag seem to be intensely indulging in the roles they are performing.

This is what makes these photos different from Carnival cross-dressing: the soldiers here are displaying true feelings under the pretext of just having fun. The moments when fiction comes closest to reality are the ones taking place near the front. There, the difference between and audience often simply melts down to the ones performing as women and the other ones becoming their men. And, something I find quite poignant, I have no photo where one can discern any kind of estrangement by any of the attending men. Everyone gets their specific pleasure.

The pictures in the book are divided in four categories or subjects: Rekrutenzeit, Kompaniefeste, Front and Kriegsgefangenenlager. Were these categories clearly recognisable for you from the very beginning or are they the result of a process of studying all the material you had collected?

This became evident only after looking at the cross-dressers photos as a whole. It makes sense because these were the four stations that soldiers would go through. Each station represents a very different situation which influenced the performances visibly.

The recruits were still juveniles and one can clearly see it. Then, the Kompaniefeste (Unit celebrations) were staged theatre plays for an audience, whereas in the front line the cross-dressing tended to be much more primitive, spontaneous, and it took place in the small core groups of soldiers. The most elaborated ones were theatre plays in the Allied Prisoner of War (POW) camps, were the soldiers would remain isolated for many months, sometimes years, with plenty of time to tailor their dresses, build a stage and write plays. The POW cross-dressers already anticipate homosexual subcultures of the 50’s and 60’s.

You underline the need to write the history of the Kraft durch Freude organisation.

Not of the official front theatres by the Kraft durch Freude organization or by the Ministry of Propaganda. Both have been rather well researched. But there was another front theatre which has not been researched at all: the spontaneous, improvised plays by soldiers themselves. Here is where we find the cross-dressers, not in the official ones − not only because it collided with the Nazi ideology, but also because the official frontline theatres had, of course, many female actors.

Soldier Studies is the conclusion of a project or your search for Wehrmacht snapshots is still in progress?

Photos still keep coming in that surprise me. As long as this happens, I will try to reach further.

As I see it, your book is more an invitation to see and welcome questions about how we interact with visual images, memory, feelings and history rather than an aim at making any judgements or radically one-sided/literal interpretations.

First of all I wanted to highlight the fact that these photographs exist. What do we see? One might see just men dying to have fun. Or expressions of hidden sexual desires. Then again they are all German soldiers in World War II, Nazis so to say, with all implications this gives. This ambiguity, the multi-focal is what struck me the most. Interpreting, categorizing would have meant to take away the fluid in which these photos become telling.

Still, do you feel they necessarily introduce some specific insight to look at the Nazi ideology or, rather, the German society of that time?

I think the insights that these photos provide are not so much on the ideological side – although, as I have pointed out, a certain notion of hyper-masculinity as part of the Nazi ideology comes into play. The twist is to see men in joyous, open moments and yet to know that they were Wehrmacht soldiers. I hope it provides some insights and understanding on the human condition, on the experience of war, which we too often imagine as a constant roar of thunder, explosions and fighting. The better we can see what actually happened – and how – the more difficult it becomes to answer complex matters with simplistic explanations.

Martin Dammann, Soldier Studies. Cross-Dressing in der Wehrmacht, Hatje Cantz, Berlin, 2019.

(1). Georges Didi-Huberman, Vislumbres, Shangrila, 2019, p. 129.

Photographs:

1-5. © Collection Martin Dammann.

6. Martin Dammann.