An Interview with Khaled Hourani: First Intifada Was an Artistic Project (by Lela Vujanić)

An Interview

Khaled Hourani:

FIRST INTIFADA WAS AN ARTISTIC PROJECT

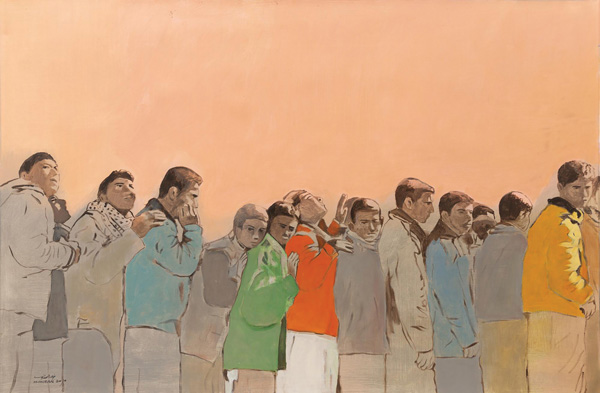

“I always argued that the First Intifada was an artistic action,” said Palestinian artist Khaled Hourani, almost immediately upon meeting me on the patio of his Ramallah apartment. We spoke at the end of September, when the temperature was still high; you could feel the summer breeze in the air and hear the drums of the Third Intifada, played by youth born in refugee camps. As international organizations like to put it, “security conditions were deteriorating” all around us thanks to decades of Israeli dispossession, violence, and occupation.

Khaled Hourani is a critical, peculiar institution. His prolific artistic practice encompasses painting, sculpture, writing, curating, and conceptual art, but he is also a part of the Palestinian collective body — crossing boundaries and limitations and constantly engaging in dialogue, the rule of art, and the possibilities of the present moment.

Recently, I saw his work in the gallery of the Walled Off Hotel, in Bethlehem, before meeting him in Ramallah. As we talked, we were often joyfully interrupted by his dog Samra, who was simply showing off, and accompanied by the sharp but familiar sounds of the kitchen as his family prepared for dinner. Hourani often says yani between sentences, which, as he explains, is Arabic for “means.” He laughs a lot, like one of those forever-young people who have seen and experienced a lot — and not always in the most favorable circumstances — but who still maintain the ability to ignite the spark of something new. We rolled cigarettes and sipped mint tea as our conversation drifted, in a cloud of smoke and steam, to the lofty heights of art and revolution.

***

Your work spans several decades and mediums — paintings, sculpture, conceptual art, writing, and curating. What has changed over time in your approach to art and issues around you?

I work in different mediums, yani, with different concepts and issues from time to time. But I can tell you that during Covid, things changed. It was a unique time, with isolation, silence, being home, and social distancing — as if suddenly we had the luxury of having time to be at home and do art. Unfortunately, it was not like this; I was shocked like other people around me. This mandate to keep going, to continue doing what we were doing before, was not easy. I didn’t use this empty or quiet time to produce art. I quit being an artist for maybe a year while rethinking the rule of art.

I saw your latest work, part of a group exhibition at the gallery of the Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem, last week. What prompted you to go back to painting?

I started walking as part of a local hiking group to change the atmosphere of being home all the time — to enjoy the landscape, mountains, and trees. But I figured out that even in such small actions, the wall and the politics are still there, even if you want to forget about it. Yani, wherever you go, you will see the wall, you will see the settlement. It gives the whole landscape a different meaning.

At that time, I was taking photos during my hiking trip, thinking about the landscape, especially when it was morning or the golden hour in the sunset. It encouraged me to go back and do some paintings. I did a series of small works, a project called “Unnatural Landscape.” The work that you saw last week in Bethlehem is part of this. It started as a project about the landscape and the wall, and how this construction, this ugly concrete, yani, tries to cut, separate, and destroy the scene. What kind of effects does this wall have on the landscape, especially from a distance? I can see, when close to the wall, what kind of damage and social side-effects the wall has between the farmer and his land, the family and their relatives, between a city and a village. But also, from a distant view, for the one who wants to hike only, the landscape has a different meaning. We live in a high area here in Ramallah; when you look toward the sea, you can see different layers of mountains, but there is no empty landscape without settlement, without the wall.

Going back to one of your previous works titled “No Refuge,” where you dealt with the relation of the actual and the imaginary — the relation between art and reality — how do you see the role of art in this specific context, a context of “ugly concrete,” or to put it differently, in the context of the brutal reality that goes beyond what we could possibly imagine?

The relation between reality and fiction drove my thinking many times, and I keep coming back to this concept again and again. The line between reality and fiction has disappeared. It was never in our minds, my generation, that we would compete with news, since art cannot come up with such fiction.

Regarding the Russian ambassador who was killed in Ankara in a gallery space — I did a huge painting about this, which was part of my retrospective in Jordan, in 2017. I chose this specific subject because the gallery space, or art in general, is considered a safe zone; yani, with everything going on outside, you go to the gallery, and you see the outcome or the result of what’s happening outside. It is something that talks about something else, it is representation. But in this act in the Ankara exhibition, when the ambassador himself was killed, the gallery was not a safe zone anymore. It is a declaration of action in gallery space. Art is not protected; there is no safe zone to run away from the catastrophe outside.

We are in a competition between reality and art. Take, for example, the resistance — it is a kind of artistic action, because for a civilian to stop a tank or demonstrate against military police, they need imagination, and it looks like fiction. What encourages you to stand for something, to dream of having a different life, a better life? It’s a dream; it is fiction.

That’s an interesting point, to look at civilians as artists of the resistance, not the other way around — artists as political activists.

I was always arguing that — I did lecture on this in Lebanon — the First Intifada was an artistic performance or artistic action. The uprising was not only political, as everyone tried to read it in decision-making circles, academic institutions, and the Western media in particular. It was culture par excellence, and deep to the extent that it was not possible to understand with the usual tools of political analysis. At that time, the Palestinian cause was in constant decline, the people were frustrated, and the national movement was eroding. So, at an unfavorable political moment, if politics is impotent and the national movement is in decline, then only culture and art are left as the main engines. Where realism ended, the impossible began.

The uprising was like announcing a revolution not only against the occupation and its politics, but also against all its causes. People did not revolt only against the military machine and the barriers. They revolted against poor education and health care; they revolted to return to the land, and to home farming and solidarity; they revolted against the way of life that was denied them.

The beginning revealed that this uprising had no leadership. On the contrary, the movement its protests came from the bottom up. I am talking about the beginning of an uprising that challenged art and surpassed it. The uprising is an artistic event, and people are artists until proven otherwise.

You are fully recognized internationally. Your work has been exhibited in major galleries of contemporary art, and it is part of the collection of Western museums. Considering the political nature of your work, on one hand, and the fact that you come from occupied territory on the other, what was your position abroad, structurally speaking, as a Palestinian artist? Did you experience accusations of antisemitism — which happens quite frequently with Palestinian artists and intellectuals — or any sort of Western gaze toward your work?

Art in Palestine is not treated very well, for many reasons. Artists suffer; they get arrested, their work is destroyed, and some are not allowed to travel. I was allowed to travel, but I was arrested. I would like to be arrested for artistic reasons instead of political ones, but they do not consider you an artist; they consider you an activist if you do something encouraging or promoting a national issue. Our political issue is cultural-issue number one. No artist, no cultural institution can avoid this, even if they are not involved. But it is hard to think about art as separate from politics, anywhere. Art is sometimes more political than politics itself.

There was a lot of solidarity at the beginning, during the Arafat times. In 1967 and in the 1970s, after the war, they wanted to treat Palestinians as victims, and they wanted to hug them, to give support. This is not a bad thing; this is a human reaction: otherwise, it would be a catastrophe. It doesn’t mean that there was no good art at that time. For me, I prefer to be treated as a human being, not as a victim first; I don’t like to think of myself as a victim, or to portray victims in my artwork. Art is not about complaining; it is about being critical. It is about seeing things from a different perspective. It’s about witnessing, about encouraging, about longing for a better life.

So, when I was invited to Documenta 13 with the Picasso project, whether they liked Palestine or didn’t like Palestine, it was considered an art project that deals with the border between curating and art practice itself. Politics is there from the start; it would have no meaning to bring Picasso to some normal country, and it wouldn’t be my priority. Palestinian history, Palestinian issues, the checkpoint that the artwork has to come through, the image of policemen protecting an artwork — the Palestinian gunman-as-fighter, suddenly standing in front of a painting — this is what made the meaning, what made the project.

Yes, the famous “Picasso in Palestine” project. You wanted to bring one picture, one painting only, “Buste de Femme,” part of the collection of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, to be exhibited in Ramallah. I am not sure that readers, many of whom will have seen Picasso regularly exhibited in their home countries, know what kind of speculative thinking and action was needed for this project to come to fruition. So, could you please elaborate the impossibilities that you were facing in bringing Picasso to Palestine? And how challenging was the whole process for you personally?

It was a very challenging project, a very risky project. The main question was, how to bring an artwork from a museum in Europe to be exhibited in a war zone? And then, how to convince the museum, since it must have the guarantee that the artwork will be in a safe van, in safe keeping — this was the first thing the insurance company asked for. We had to build a museum because, at that time, 2009 to 2011, we didn’t have a museum. And we needed money. So, it was kind of a miracle, and we had to work in fiction, too.

I invited a filmmaker from the beginning, before I had even ten percent of the budget, to film all of this, even if we didn’t succeed. But there are artists, or people who believe in art, everywhere — this is also what the Picasso project taught me. For me, this was a learning process. I didn’t know how this would work, or if they were going to give me that amount of money, because it was a few hundred thousand dollars in question. And there was also a contention: Do we need such a thing in Palestine, with all the crisis at the time — and to bring only one Picasso painting? Is it really worth it?

The artwork had to be protected 24 hours a day. We had to create a small museum according to strict criteria of humidity, temperature, security, lights, everything. People needed to go one-by-one to see it, or two-by-two, because it was a four-by-four-meter museum, and ten people breathing near it wouldn’t be healthy for the artwork itself. All these kinds of concerns.

For me, it was a project about this small museum, an empty museum after the work was returned. We were also questioning the solidarity part of art action, because a lot of things could be considered solidarity activities, but this doesn’t look like it. And we were questioning, of course, the relation between museums in Europe and the rules about the Third World and war zones, areas of conflict.

I was sure that it looked like a joke at the beginning, when I wrote a letter to a museum and said, “I want to officially borrow artwork from your collection and bring it to Ramallah, where we don’t have a state, we don’t have a museum — all these basic things — we don’t have an airport. We have nothing, but we want to try to satisfy all the criteria — except maybe the state.” [Laughs.]

The project was a major success, not only internationally, in media and at Documenta 13; Palestinians also greeted it with much interest and excitement. What happened with this small museum after the exhibition of this one piece?

A German filmmaker, who was visiting the [International Academy of Art Palestine; see below] and the museum a few months after the painting went back to the Netherlands, asked the same question. He was sitting in this empty room and asking what I was going to do with it, as if I had to do something as an artist, as if I had to do a new project. Your question now invites me to think more as an artist. Because in my way of thinking, doing a new art project is a kind of declaration, as if what I did is not enough, as if I need to do something, as if there is the necessity of saying something new. Why do more than one project?

We still have visitors; they want to take photos in that room and its empty square, where the painting hung. You have the same story in art history, like what happened with Mona Lisa; the disappearance of artwork is a concept in itself. If I want to do it again, it will come across like gossip —that is, when you say something extra that’s not needed. I think the empty space itself is something. But I am very satisfied with the kind of art that is coming up around the Picasso project. There was a comic book by American- German artist Michael Baers; he did “An Oral History of Picasso in Palestine,” he did a huge book, seven-hundred-and-something pages of drawings; I will show you …

What Michael did — research, being involved, visiting, interviewing, and drawing — he is still involved today. The thing is, he knows more about the project than I do.

The small museum was located inside the International Academy of Art Palestine, where you served first as Artistic Director and then as General Director from 2007 to 2013. What kind of institution was the Academy?

It was like an art project, a very experimental kind of institution. We had an agreement between our Academy and Oslo Art Academy, so students who wanted to study here knew from the beginning that we were not looking to have accreditation from the Palestinian Authority because we were critical of their accreditation criteria. If you want to follow in their steps, you can go to a regular university. If your passion is art, however, you are welcome.

At the time, there were adventurous artists who were unknown. In insurance companies, you will find artists; in police stations, you will also find crazy people who believe in art and artists. This is the magic that bring things together — brings crazy people, crazy teachers, and crazy students together.

The Academy has influenced the Palestinian art scene very deeply. It was a bridge between the old generation, their experience, and the new generation; it showed the needs of both generations to negotiate the terms of art, life, and the role of art. It was an open institution, even for non-students; we did a lot of tours, a lot of open lectures, and we invited people from everywhere. It was not about the classic way of teaching. It was an alternative.

It seems that you were, at the time of your engagement with Academy, already a bit disillusioned with previous experience in the Ministry of Culture. I also worked for the Ministry of Culture in Croatia, having a dream of a different kind of state and a united front within the scene we represented there. Needless to say, these dreams crashed rather abruptly in the course of everyday politics. What was your experience? Were you the general director of the Fine Arts department?

Working for the Ministry of Culture was like fiction. [Laughter.]

I was the general director of the Fine Arts department. It is a very big name for a small department. In the beginning, the Palestinian National Authority was the [Palestine Liberation Organization] institution, and the PLO was a revolutionary kind of institution; we were proud to be part of this institution, but it became old and corrupt very quickly. They were not into content, but rather institution-building itself. It attracted all kinds of artists, not only visual — a lot of musicians and writers got involved, too.

The PLO had a state kind of structure, and it started all these departments — literature, visual arts, cinema, dancing, and theatre, each art had its own department. I was invited to work there, in the Ministry of Culture, though I didn’t apply myself. These were dreamy times, and I did many things that I am proud of — a lot of international workshops and biennales. But I figured out that art has its own life away from this government institution, and that art has to think about how to see this government from a critical point of view, too.

Throughout your life, you invested yourself not only in your artwork but also in what we could call institutional design. I am referring not only to the Academy and the Ministry of Culture, but to initiating or being present in other artistic and cultural initiatives, supporting younger artists, and building a scene.

I see institutions as artistic things, as models. For me, the Academy was a model, a new model that doesn’t look like teaching art in a government college or a university that has accreditation from the government. It is kind of parallel or alternative. For example, to do a project like “Picasso in Palestine” would not be possible as an individual artist; it needs institutional involvement, which the artist cannot guarantee, no matter who the artist is. I believe the artist is an institution that is sometimes more important than the institution itself. But sometimes, you have to create an institution. However, it has to be flexible enough. For example, in the Picasso project, there were a hundred individuals and institutions involved; it was not only the artist. A lot of issues needed to be solved, including media, taxes, security, insurance, and technical criteria. Palestinian guards — they don’t have experience in dealing with artwork or convincing the Ministry of the Interior that this artwork needs to be protected 24 hours a day. There were many people working, and the last one working was the artist. I was here, and sometimes I got stuck and didn’t have a solution for things. But there was a group and group mechanism, and together we found a solution.

For example, between the Qalandia checkpoint and the Palestinian checkpoint, there is a no man’s land, a grey area. There is no possibility for Palestinian police to go there. Israelis are not allowed to go either, except by force, and then there will be demonstrations and tear gas. So, there are a few kilometers between the checkpoint and the Palestinian police. How to convince the insurance company that it is OK there will be no security guards in this specific area? I tried with the Palestinian government and asked them if they could go and talk with the Israelis only for this operation, but the Israelis refused. I couldn’t ask them to have Israelis come …

How did you resolve it?

Through the media. My assistant came up with this brilliant idea that she would write to the museum and the insurance company to invite the cameramen from Al Jazeera and CNN; it would be protected by cameras instead of machine guns. It was live on Al Jazeera. Who would kidnap artwork in such circumstances?

What are the main challenges for the contemporary Palestinian art scene, especially for the younger generation? Is there any official state support for artists these days in Palestine?

Art is in a very critical moment everywhere, yani, but good artwork will find its own way to exist. You can do a great project for zero budget. Some projects need fundraising and money to exist, but this is the magical thing: some don’t. Artists need to invest in their passion and creativity. If you have a great idea, it will convince others, and money will come.

I am not sure if the government or other official institutions are interested in what contemporary artists or young artists are doing, because it is also very critical work. They will not like what they produce, so they will never support them. And independent art institutions, NGO institutions, are worse than a government; they have their own censorship.

There are two big institutions in Palestine, bigger than the Ministry of Culture. The Qattan Foundation and the Palestinian Museum have a big budget and nice buildings; but for a while, they only work on certain topics, strange topics. They only want to work on the past and memory or the future, nothing about the present moment. They are ignoring what’s going on now. They talk about Palestinian life next to the sea, before 1948, which is good; but I am not sure this is a necessity now. When they invite you, they invite you to work on this or that concept, topic or theme. They don’t ask you as an artist, “What you are doing?” and then invite you to come and work with them. They tell you, “We are thinking about doing this exhibition about this book published in the ’80s — what’s your contribution?” That’s not my cup of tea.

They create their own themes, and even with this concern about the worries of the young generation, they are not actually worried about what they think. They invite them to ignore their issues and their life and to think according to their agenda. And their main issue is to keep going; their function is not art. They are employees in this machine called an institution. The artist is not about the institution; his or her concern is about art and the space for freedom.

Palestine was, at least in the PLO period, considered a secular Arab country. There is a growing concern in recent times of re-traditionalization, especially along religious lines, that also affects art.

To be honest, art was attacked by two governments. By Hamas, because of its beliefs — it thinks art encourages people to use their imagination, that it encourages both genders to get together, especially dancing and theatre, and encourages people to think outside the box. You know what culture does. They like a kind of art and culture that is more conservative. They don’t mind if you shout out against the occupation — but don’t talk about your freedom, don’t sing about your own life.

But the Palestinian Authority and the Ministry of Culture in the West Bank recently started to become very conservative, too. There was a march for the theater a few months ago, and it was attacked by some conservatives because it looked like a gay demonstration — which it wasn’t, but even if it was … They were attacked, and the police were not protecting artists; they tried to be neutral.

This was not the case before. I wrote in a post, “As if there is no art in Palestine in such a situation — in Gaza or here.” It is a very bad sign, and it was never like this before, the Palestinian Authority letting conservatives — I am not sure who was behind this, but it was clear they let things happen. They didn’t protect artists or theater. And this was not the only case. There were other shows, concerts, and events that were canceled. For me, this is censorship. The government likes conservative, nationalist work, supportive of their cause, but not the kind of work raising questions. Because people are critical of authority now, unlike before.

You’ve had the opportunity to travel, and I am guessing that you’ve also had opportunities to leave Palestine. Given the circumstances and what the so-called international community calls “deteriorating security conditions,” did you ever think about leaving Palestine?

Now, yes; before, no. There is less hope now than before. There was an article in the newspaper recently asking, “If not a two-state solution, then what?” I was thinking about my son, the future of his generation, who will not suffer from the same issues we are suffering from. But the thing is, we start counting from zero, and things are worse than before. The Palestinian national movement, the PLO, is defeated now. We should face the fact that this project has collapsed. I don’t think they will manage to succeed.

In the future, the occupation has to come to an end, for sure. But the element that made Palestinians stand for their rights historically was Arab support, international support, and unity between the leadership and the people. All these elements are nonexistent now.

And yet there is nowhere to go. Where else to go? Now, is it better here or there?

***

After our interview, Hourani and his family tried to call a taxi for me, but I convinced them I could easily reach East Jerusalem — also in occupied territory — by myself. I caught the last bus from Ramallah and soon arrived at the infamous Qalandia checkpoint, the same checkpoint that Picasso’s “Buste de Femme” once passed through. At Qalandia, I was met with full-fledged drama, flashing red lights revealing soldiers in full military gear.

It really is like fiction — to me, at least.

Soldiers conducted a search both within and around the bus. Meanwhile, police dogs sniffed frantically to see if there were any terrorists about, ready to destroy it all. The multitude of weapons hanging from the soldiers’ bodies almost knocked against us passengers, none of whom seemed seriously afraid — nor was I, in the end. It was clear that this was a common situation. After all, this must happen to them every single day: they set off somewhere on this tiny piece of land, and then encounter any number of checkpoints and barriers along the way, in the end getting nowhere.

After a two hours’ wait, the bus was allowed to move on — but backward instead of forward. Some kids from the bus led me away, almost by hand, telling me we could still cross the checkpoint on foot. A young Israeli female soldier yelled at me relentlessly; I answered all her questions and finally passed through.

I was relieved to see several buses parked on the other side. Displaying an instinctual Croat–Arab understanding, the bus driver assured me that everything was OK, that he would take me almost to my doorstep. “Are you from Modrić country?” he asked me, referring to the world-renown footballer. I smile — then and now, while writing this all down — thinking that art can’t be dead yet, at least not in this part of the world. Everywhere you look, there are wonderful, crazy people — artists, that is, until proven otherwise.

An interview by Lela Vujanić