See David Renggli’s 8 unique paintings, created exclusively for Collecteurs Capsule Editions

Moments after we got on the phone, my broadly settled notions of David Renggli shifted. Better yet, they evolved; an unsurprising circumstance, of course, if considering whatever forms of virtual written interaction still always lack an essential human component: a tangible physicality that deliberately materializes the reflections and meanings of a stranger, whose face—especially thanks to Google images—you’d involuntarily recognize in public situations, yet not (ever) come to understand. Nonetheless, the predictable shift from email to phone seems noteworthy here; hearing and listening to an agreeably soft-spoken voice on the other line (and across the Atlantic), a reliable artifice begins to form around the artist’s practice and otherwise everyday observations. Still witnessing as an external viewer—just steadier, and maybe sometimes closer—Renggli pulsates with ideas that often end, yet not conclude, with a certain type of playfulness towards our contemporary ways of existing. Abstractions that reference the selfhood of a 21st century and beyond, become subtle impulses for the loss and gain of meaning, necessarily resulting in something purposeful. Or, at least temporarily permeable.

Within his widely-ranging creations from painting to sculpture, he laughs about (but really with) us, himself included. Throughout, however, whatever new explorations that aren’t meant to harm (but to heal, if anything), Renggli detects in his artistic outlets elemental, philosophical notions that might spontaneously leave us dumbfounded, just because they’re so absurdly humble in their beauty and the future inside them. His anecdote about randomly watching a TV documentary in which brown bears suddenly appear on scenic beaches, is one of those moments. That lovely silence that emerges when we try to grasp something meaningful.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

There’s authenticity in his seemingly-voluntary mistranslations of culture that resurface in and as the work. In Renggli’s universe, everything’s cruel, yet funny. Pathetic, yet worthwhile. Futile, but essential. Kind of like Instagram, an example of some of his underlying regards when it comes to his practice: a perfect reflection of our internal desires and destinies, ever-producing and unavoidable; our life, lived the way it is. Not the way it should or shouldn’t be.

Lara Konrad: Sometimes it’s difficult to instigate a conversation with a stranger. In your opinion, what’s the right setting for a dialogue to unfold?

David Renggli: Most importantly, there needs to be some type of attraction and curiosity. An entry point to a dialogue needs to be available. After that, you can either start conversation with a compliment, or a provocation. In that sense, I also think it’s important to make a conversation personal so the other has something to hold on to, and there’s something to develop and return.

It should allow openings and inspiration. An ideal setting is where everyone involved, develops and inspires each other.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: I think openings for such settings often fail, since we necessarily want to exude the notion of absolute awareness. Not knowing, not understanding, makes us look weak. Or worse, dumb. Hence, this deeply-instituted way of public behavior has allowed for only certain types of conversations to take place. It’s a shame; dialogue can (almost) never grow from here, since they’re just reproduced opinions.

DR: Yeah. For example, if someone lives in the countryside and doesn’t properly speak the native language, yet makes a statement or has a really good opinion, the form is still ‘wrong.’ A listener mostly concentrates on the form, rather than seeing or hearing the content.

LK: Do you think a personal connection to an artwork is necessary in order to live it most? Or, can we experience art equally intense if personal memory isn’t part of it?

DR: I’ll answer that with a question: do you think everybody sees the same when looking at something? What do you picture if you read: dog, house, tree, nude, banana?

LK: A while back you mentioned you had a “philosophical problem” with people having an opinion on TV, in the press, spreading it everywhere.

DK: I get annoyed when it’s merely about reproducing and spreading an opinion. It’s fine to have an opinion that’s available for renewal and negotiation. It could even be the foundation for a great dialogue. An opinion just needs to be aware of its own flexibility and relativity, a tool to leave itself. It should be an invitation, or a base, to go elsewhere. An inspiration, or even more so, a question rather than an opinion.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: When it comes to your art, would you actually want it to exist devoid of personal opinions (if there is even such a thing as personal opinion…)?

DR: I don’t necessarily think so. I think that art has the privilege of not being bound to a sort of materialistic or mathematical logic. Yet, at the same time, it can take part in a dialogue based on such forms of logic.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Various factors often bestow your work with a type of lightness. There’s the abundant usage of color, the incorporation of certain readymades that immediately allude to stereotypical conclusions—like the universally representative model for a woman’s handbag; a bed that represents a kind of joie de vivre, somehow entirely bypassing sexual connotation and conventional human melancholy. Do you want your audience to arrive at a certain point of whimsicalness? And while we’re at it, what’s a bigger compliment to you as an artist: laughter or grief?

DR: I love the energy of laughter. Still, I think it depends where one assumes a deeper sense of self-responsibility.

As previously mentioned, I see the defining attribute and strength of art, the fact that it’s not necessarily bound to logic. I think in that sense, a sort of whimsicalness with the hint of a smile is intended.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Can you expand on the idea of assuming a sense of self-responsibility that comes with grief or laughter? Are you referring to remaining within ethical realms, to not overstep boundaries?

DR: It’s not nice to laugh at someone who just fell down the stairs. Yet, there are times it looks very funny. It’s interesting to understand why something is funny, how even cruel things can be amusing.

Whatever it is, the energy inside your body is still a positive feeling, I think. Maybe things are funny because you aren’t part of it, while sadness is more personal. Things appear sad once you picture yourself in the same context. So maybe it’s selfish to think something is sad what you see an image. Often laughter is judged as superficial and grief as the opposite, as something deep. Deep shit….

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

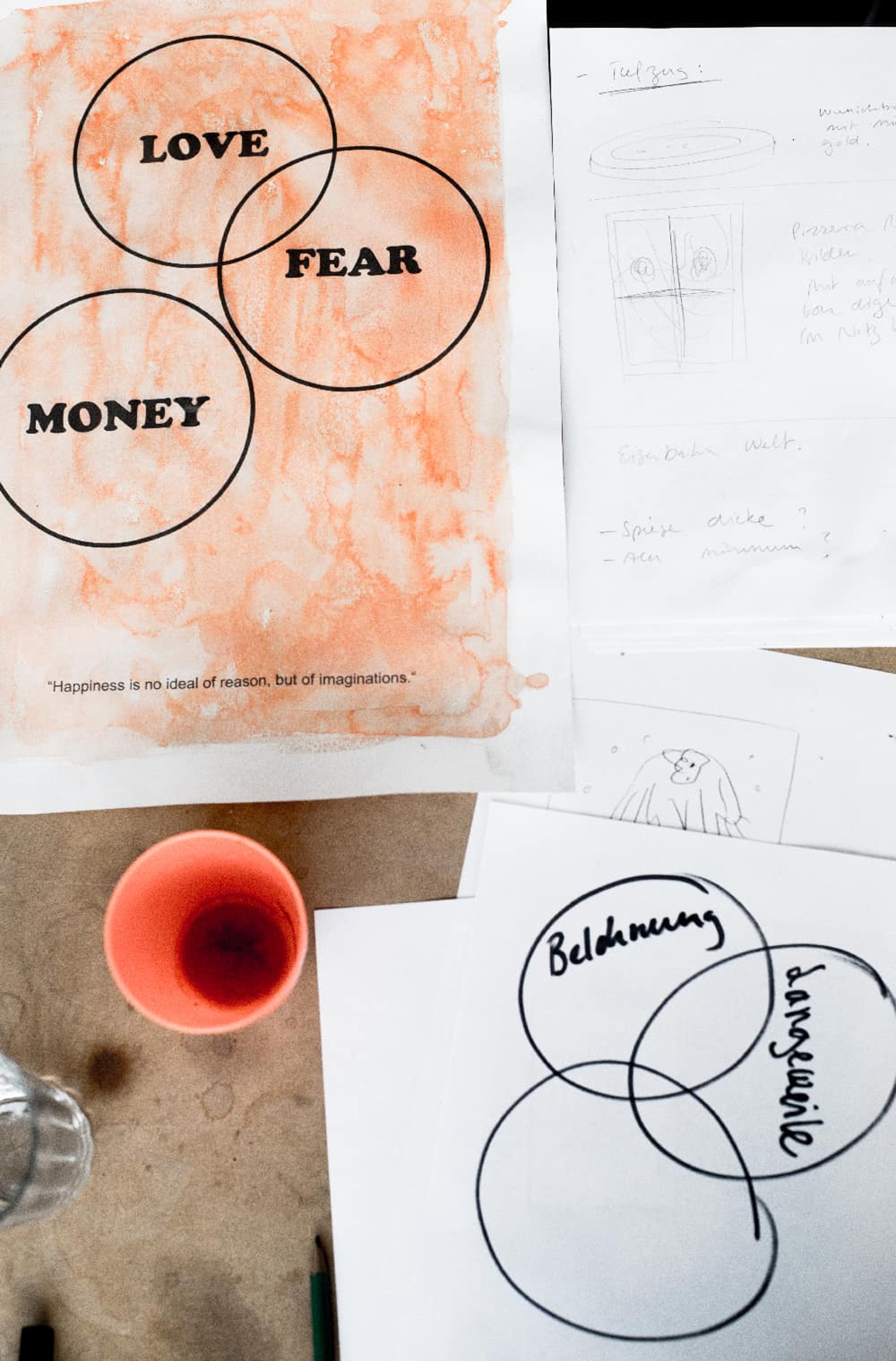

LK: Talking about “deep shit,” tell me a bit about the edition you made for Collecteurs. I’m particularly interested in its usage of stock image.

DR: The series plays with the idea of canvas; since it’s transparent, the background comes necessarily into play. Throughout the production of artworks, a human body is generally used as a measurement for scale. Sometimes it’s also a pack of cigarettes, just because it represents some kind of norm.

LK: Was it important that the person looks at another painting within the work itself?

DR: In this case, not so much. Take Instagram, for instance, how people are often in relation to an artwork; either they are laying in front of something, or looking at something.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: You also chose a stock image, a very specific form of image in itself. How did you decide on that very image?

DR: It was a coincidence. For this other series of net paintings, larger in size, I also used stock images.

Do you know Alamy?

LK: No, I don’t.

DR: It’s a stock image provider, they always tag images with these special _A_s on top – like a watermark. I started to let these _A_s flow into the image, since afterwards it’s a also type of destruction. We always want to claim an image, own it. When I was looking for images, I found this woman gazing at a painting, and I liked that it had been ‘claimed.’

LK: It’s also interesting how the image doesn’t show what the woman is looking at, we merely assume she’s looking at art by the way she carries her body.

DR: Yes, she looks so thoughtful.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Returning briefly to your comment about how an opinion should remain flexible within itself, what opinion has recently changed for you?

DR: Though it might not align perfectly well with your question, for instance, I recently watched a documentary in which brown bears were fishing at a beautiful beach. The image was so absurd, I never would have thought about connecting these very two images, bears fishing, and a beach where people might go swimming. Perhaps it’s really banal, but I thought it was crazy. This acquired habit, this unspoken assumption of bears and beaches. I just never would have linked them together.

LK: That makes me think of Albania, when I was at the beach; people were dressed in their best clothes, walking in the sand, right next to the water. Men in suits, women in skirts and dresses. I remember so much those high heels pushing into the sand, women’s feet sometimes getting wet by an incoming wave. And all these BMWs driving along the shoreline.

DR: Crazy, they were walking in the sand? In their high-heels?

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Yes, it was crazy. Like it was 5th Avenue, or something, just in water. The image was absurdly beautiful, especially the realization of these images, our association and how they suddenly might change.

When you saw those bears, fishing at the beach, did something change in you, in your work?

DR: No, but it’s just an example how many things we accept, and don’t question. These established hierarchies that actually aren’t real, or truthful.

Polemically-speaking, we immediately connect certain images and content. I’ve never seen a bear at the beach, just in snow or in the forest. Actually, it’s a mix of manipulation and disinformation from which I deduct a type of truth. It’s like an archive of mainstream images that consciously or subconsciously form part of my perception and conclusion, and one of the very reasons why I considered it exciting. It’s an example of how many other things have established an opinion, without a solid foundation.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Yeah, we’re suddenly asking ourselves entirely new questions. Which leads me back to you, how you’re generally someone who wants to ask questions that are unfamiliar, somehow…

DR: Questions are so much more interesting than answers or statements, or opinions. A question is a type of invitation, it’s about participating, as well as the continuation of thought. A conversation should be a mutual landscape for inspiration, a productive way to challenge each other.

LK: You probably get asked a lot of questions…

DR: Yes, constantly (laughs), it’s become some kind of joke with friends…

LK: So you must be excited that we are coming to an end here.

DR: No, I love good questions, absurd questions. There are so many things that can surprise me. Like this image of bears at the beach. Something that’s just not too tied to a thought process. I usually get asked things that have been calculated. I just like to face the unexpected.

© Tom Huber for Collecteurs

LK: Don’t you think by asking such carefully-calculated questions, people seek to leave behind some type of impression? We all want to be memorable, after all.

DR: Mostly people want to impress with statements, not with questions.

LK: Sure, there’s truth to that.

DR: I do like to explain and talk about my work. Studio visits are great for that, since my practice involves so many different angles and places. But I guess those are actually statements, rather than questions (laughs)…