Artist Brendan Fernandes takes dance beyond performance in Inaction exhibition

Film, livestreams, and architectural sculptures give multifaceted voice to identity and unrest, at Richmond Art Gallery

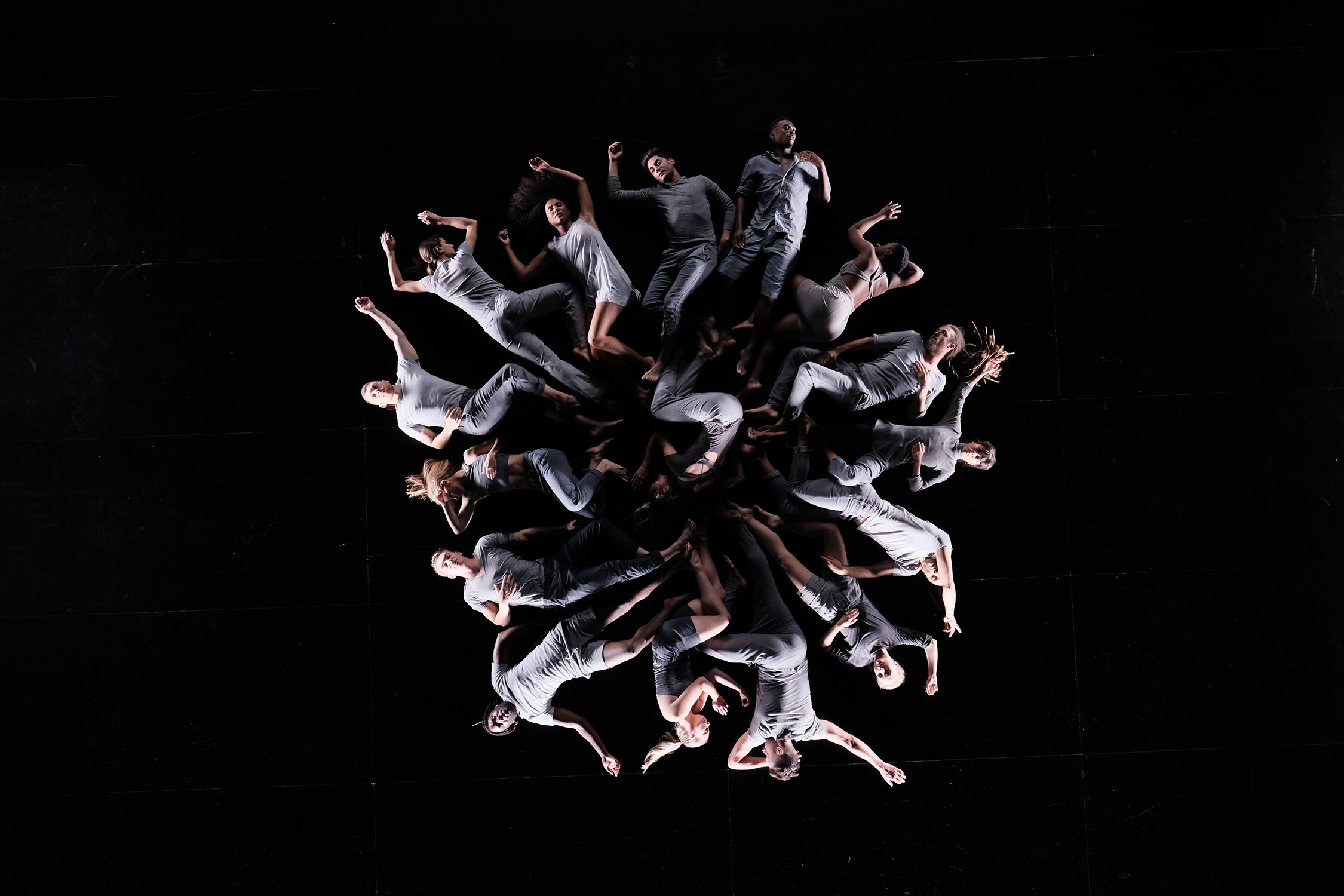

Brendan Fernandes’s single-channel film Free Fall: for Camera (shown here in a video still) was his response to the 2016 massacre at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub. On view at the Richmond Art Gallery. Image courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche, Chicago

Now based primarily in Chicago, dance-trained Brendan Fernandes devotes himself to multidisciplinary practice. Photo by Nathan Keay

Richmond Art Gallery presents Inaction from February 12 to April 3

“I AM KENYAN, I am Canadian, I am Indian, and I make art in America. I’m also a person of colour who identifies as queer.”

This rich identity is what multidisciplinary artist Brendan Fernandes drew from when creating his upcoming exhibition, Inaction. On display from February 12 to April 3 at the Richmond Art Gallery, Fernandes’s work is deeply rooted in political unrest and sets out to amplify the voices of marginalized bodies across the globe. The exhibition—which consists of his 2019 single-channel film Free Fall: for Camera, nine sculptures, and multiple livestreamed performances throughout March and April—also aims to challenge the way we traditionally experience dance.

Brendan Fernandes wants to challenge notions of dance and take it beyond performance. Photo by Kevin Penczak

“People think ‘dance’ and they’re expecting to come to a theatre performance, but that’s not what you see in my work,” Fernandes explains. “A lot of it asks what a safe space is—what space keeps me safe, what space makes me feel authorized, and what space lets me also be an agent.”

Fernandes’s work explores the mosaic of his identity as well. Born in Nairobi, Kenya, of Goan descent, he was nine when he immigrated to Canada, where he began to train in classical ballet. His focus shifted to studying visual art at York University and the University of Western Ontario after he suffered an injury. Now working primarily in Chicago, Fernandes is an accomplished contemporary artist, incorporating themes of political unrest, migration, and queer culture into his multidisciplinary works. Inaction is just one of his many internationally recognized exhibits.

He created the structural component of the exhibition in conjunction with Chicago-based architectural firm Norman Kelley. After Fernandes was introduced to cofounders Carrie Norman and Thomas Kelley, the trio investigated how space can impact and become impacted by the existence of a body.

“I normally work with architectural devices like walls and floors, so I wanted to push it further in my process and my concept,” Fernandes explains. “Now I think more about the space—how is it affected by change, by burden and how does it challenge the body?”

The nine minimalist sculptures in Inaction were designed specifically with Fernandes’s dancers in mind. The pieces include abstract black-and-white floor sculptures, hanging brown ropes, and a padded raised triangle platform for the performers to dance on and with. His choreography allows the dancers to challenge the passivity of traditional museum spaces.

Installation images of Inaction at the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery at Wesleyan University in 2019. Photos by John Groo

The exploration of space is also at the forefront of Free Fall: for Camera. The film was created in response to the 2016 massacre at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub, in which 53 LGBTQ2SIA+ individuals were wounded and 49 were killed when a shooter opened fire in the venue.

The film, Fernandes explains, incorporates moments in which each dancer falls, representing individual victims of the crime. As a politically driven work, Free Fall: for Camera offers queer and POC bodies the chance to reclaim a space that is free from marginalization. It demonstrates resistance, as the dancers restore their power in a space that was once reduced to violence and havoc.

Fernandes’s choreography examines the moment when a dancer’s body collides with the floor—in both intentional and incidental falls. Sixteen dancers, dressed all in grey, shift between moments of precise geometric shapes and movements that are fluid and free. They maintain a tight intimacy, their breaths overlapping the pulsating rhythm of the film’s score. Varying from aerial views of sculptural group formations and close-ups of the moving body, Free Fall: for Camera explores the concepts of falling and recovering, separating and recollecting, and strength through vulnerability.

“The main metaphor of Free Fall is this idea that the dancers move and then they fall, and then there’s a stumble where the body collapses,” Fernandes says. “There’s vulnerability, there’s this moment of hurt, of pain, but then there’s this resilience of ‘I am going to stand up.’ So, they get up, and they keep going again.”

Resilience, Fernandes notes, is also a driving force behind his upcoming work. After his injury and leaving the dance world behind, Fernandes has returned to the performing-arts scene. His new work aims to confront, overcome, and heal the traumas that exist within his past, present, and future identities.

“I grew up in Africa and my family is Indian….Those trajectories of migration and movement through colonial histories have traumas and residues,” he shares. “I am not a victim, but now I need to think about it in a different narrative and take on the roles and responsibilities of making change that will then support me and my community.”

Fernandes’s complex and fluctuating identity provides a unique insight into how he sees himself within these roles and responsibilities. Inaction was initially exhibited at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, but is now due to be presented at the Richmond Art Gallery as its first collaboration with an American institution. This, Fernandes believes, provides a tremendous opportunity for Canadians and Americans alike to reflect on their contribution to queer and POC politics.

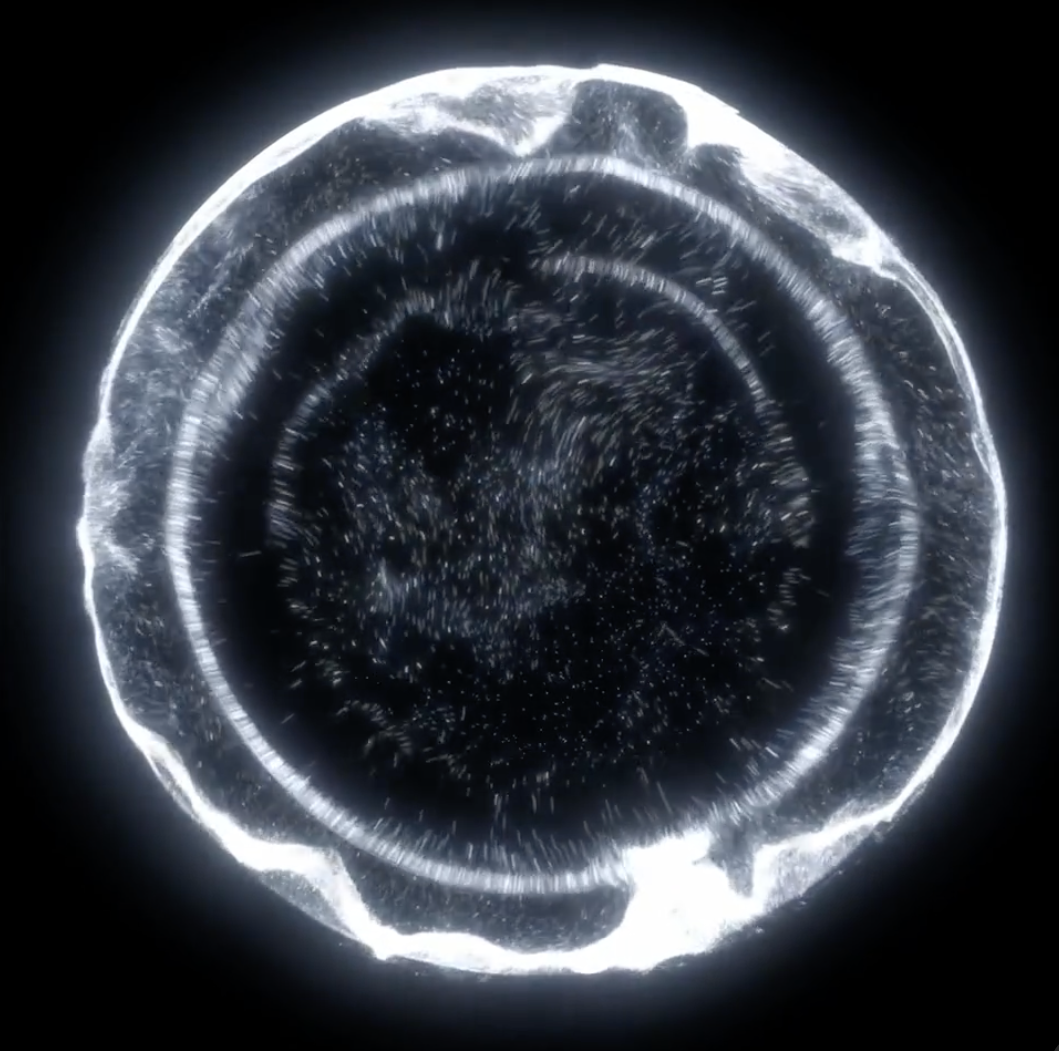

Brendan Fernandes’ Free Fall: for Camera (shown in a video still) examines the moment when a dancer’s body collides with the floor. Image courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche, Chicago

“Because I live and work in both countries, I can see that idea that people have created that Canada is perfect—we are this social country, we have no problems, we take care of everyone, we have free health care,” Fernandes says. “But we have so much work to do as well. We aren’t perfect—we still marginalize our Indigenous communities, and we still have terrorist groups that are threatening POCs.”

“A big part of Inaction, specifically the film [Free Fall: for Camera], is that when they fall, other dancers come to nurture them, and they care for them, and they pick them up, and they support them,” he explains. “That’s a metaphor for what we need more of in our society, both globally and in our country. We need to see that we are all the same—people aren’t different.”

More often than not, Fernandes’s work revolves around the idea of thousands of people coming together to witness art—promoting, cultivating, and celebrating a sense of “us”. He intends to use the exhibition to create conversations of support for POC bodies, and to bring queer politics to the spotlight of the arts scene. Inaction does this by inviting its viewers to the limitless virtual space, allowing them to witness the work with people around the globe. This space of togetherness, or “collectivity”, as Fernandes says, is where we are invited to advocate for equality.

“I think that’s the crux of my work—collectivity,” Fernandes says. “I want to create a voice and a space. As marginalized people, we’re not being heard and we’re not being seen. But if you’re a part of a collective, we all understand each other. The space becomes a space for our voice, and we’re all sharing it. Because when we come in as a collective, we say that we are the same.”

While the importance of his art is timeless, Fernandes does look forward to the day when his career can lead him in a different direction. “When the work is done, I can have a break,” he says. “Right now, people don’t get it. So we have to make the voices heard.

“We all need to be self-reflective,” he urges. “We need to make the move forward. That’s what my work is about.”

Inaction, Fernandes explains, suggests a path through which we can end the violence against queer and POC bodies. But it also demands that we, as a community, actively work toward doing so.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it offers hope—hope for a future where we are all heard, and all heard equally.