There’s something potently transfixing about hearing British artist John Stezaker speak about his work. I don’t know about you, but “I work at night, to subvert intentionality” is something I’d wear on a Vetements t-shirt. Stezaker’s films, for example the 2012 piece ‘Horse’ that contains still images of horses flashing by at 24 frames per second, are a hypnotic foray into the unconscious. His visionary collage art, mostly consisting of manually spliced and cut up 1940s found Hollywood stills unsettlingly balanced with antique prints, has enthralled people since the early 70s when he first created them as a young student, after discovering the works of Max Ernst. Yet the art world averted its fickle gaze from Stezaker for a long time, not fully acknowledging the visual impact of his creations, while the work of artists such as John Baldessari (who started making cinematic still collages a whole decade after Stezaker did) lifted its creator to the heights of fame. Around the turn of the century, the art scene finally caught up and Stezaker started showing around the world while deservedly racking up accolades. Delayed, later-in-life success is something my generation dreads beyond measure; yet people sleeping on Stezaker’s work for so long never made him waver from his devotion to it. Just as Larry Clark most recently advised in his new manifesto, he kept punching.

Still from ‘Horse’ (2012) by John Stezaker

Antwerp gallerist Sofie Van de Velde got in touch with John Stezaker because of his 2015 show in Brussels. Conversation eventually lead to the discovery of a mutual admiration of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers who, just like Stezaker, was an avid collector of old images to reappropriate for his art. An idea for a double show featuring the works on paper of both John Stezaker and Marcel Broodthaers was born, using Broodthaers pieces out of the personal collection of the gallerist’s father (famed art dealer Ronny Van de Velde). That show, ‘John Stezaker in Dialogue with Marcel Broodthaers’ has now opened at Sofie Van de Velde Gallery and if this already was the year of Broodthaers (a major MOMA retrospective wrapped in May), it just got better. As this is a special moment for Belgian and British art, we sat down with Mr Stezaker to discuss (almost) meeting your heroes, family support and what’s next.

John Stezaker by Sebastian Kim

It’s been almost forty years since your first exhibition in Belgium.

“Yes. Actually, I hadn’t thought of that. It was in 1977. Good God, it’s been forty years.”

So this is an anniversary of sorts, happy anniversary!

(laughs)

How did this new exhibition come to fruition?

“Since Sofie Van de Velde had proposed to do an expo at her gallery, I thought it would be so wonderful to show with one of my heroes, Marcel Broodthaers. It’s a mystery to me why Marcel was so interested in antique images and that’s also something that has puzzled people about my work. I suppose that I was looking for an answer from him as to why I had the same sort of fascination. Even though the era of images he was fascinated by was much earlier than mine, it interested me. So I thought that I would, as a kind of homage to him and Max Ernst, use some of the more dilapidated and ruined books of Victorian engravings to see if I could come up with new collages for this expo. And actually, it turned out be quite fruitful. There’s a whole new series emerging now.”

Before this interview, you gave a lecture at Cinema Zuid in Antwerp and you mentioned meeting Marcel as a film student at Slade School of Fine Art in the 70s. Unfortunately, there was a bit of a language barrier between the two of you. If that hadn’t been the case or if he was still alive today: what would you have liked to discuss with him more thoroughly?

“Hundreds of things. I never got an answer from him as to why he was interested in these images that were made two generations before his time. Also, he loved Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé and at that time I had only read a little bit of both but now I’m much more familiar with the literature he was steeped in. I think Marcel was quite prophetic because in a way he was a bridge figure between the conceptual art generation and the generation that I belong to, which is much more open to connecting with subjects like late nineteenth-century romanticism for example. I think American-dominated art in the post-war period was almost always focused on novelty. And so, in order for a movement to exist in Anglo-American terms, it had to represent a fracture with history. Marcel and myself as well, I think, are people who want to heal those fractures rather than create them. I believe that’s much more connected to the current generation of young artists, who have a very different relationship with history. There’s an entire generation of artists who spent a lot of energy creating homages to earlier artists, and I think he was the first really to do that through the work of René Magritte, Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Marcel Duchamp. That’s why I feel Broodthaers was so important. He was kind of the antithesis of American modernism. In fact, there’s a very strong spirit in surrealism of ‘reconnecting’. Giorgio de Chirico was trying to reconnect with early Renaissance and later with Rubens and baroque art. Magritte was trying to reconnect with Belgian romanticism. And that’s why I think surrealism became so taboo in the 70s; it was too connected with romantic ideas, the unconscious, the muse and inspiration. American modernism was dissimulative. But I think we have a generation of artists now, post-Jeff Koons even, who are interested in simulacra. The idea of the simulation now is as fascinating as it was to the surrealists.”

You would have had plenty to talk about.

“Yes, but it was impossible, really. My French was probably better than his English, but I was too embarrassed and too young. I mean, he was the hero figure for me. It was difficult to approach him.”

‘Citron – Citroen’ by Marcel Broodthaers (1974)

‘Atlas’ by Marcel Broodthaers (1975)

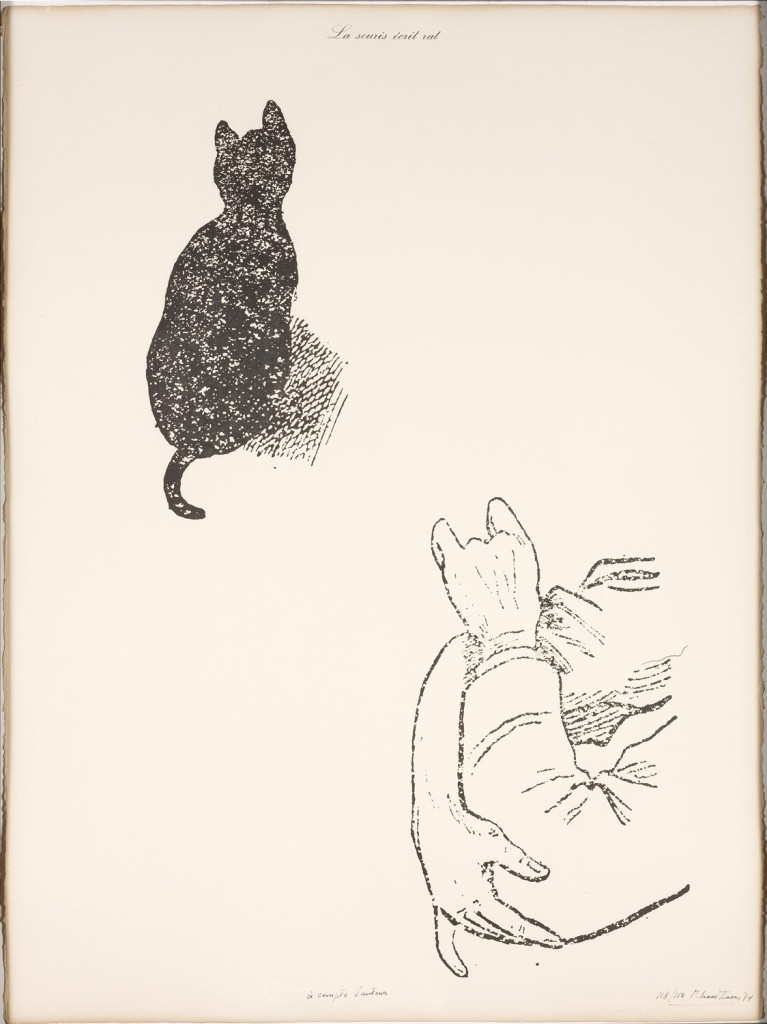

‘The Mouse Writes Rat (At the Author’s Expense)’ by Marcel Broodthaers (1974)

Have you met any of your other heroes since then?

“When I was a second-year student at Slade my professor, Sir William Coldstream, called me into his office and said: ‘Stezaker, you seem to be the only person amongst the staff and students who knows anything about this chap Marcel Duchamp.’ At the time, Duchamp was about to have a retrospective at the Tate Gallery. Coldstream continued: ‘I want you to go to a talk by Octavio Paz, a Mexican writer who recently wrote a book about Duchamp. Go to the lecture, Marcel Duchamp will be there and I want you to bring him back here for drinks.’ My professor had a wall in his studio covered in signatures of famous artists and he wanted to have a Marcel Duchamp signature, which would have made the whole thing an artwork, he thought. So I read the Octavio Paz book and the more I learned about Duchamp before the meeting, the more it panicked me. On the way to the meeting, I had an absolute anxiety attack. So I didn’t go.” (laughs)

Oh, really?

(laughs) “It was very difficult. So, I never got to meet Duchamp! The funny thing is, the show he had on at the Tate was called ‘The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp’. He had announced that he had given up art but by putting ‘almost’ in the title, he hinted at the existence of another work of art. Which of course we now know is ‘Étant donnés’, in Philadelphia. Nobody really picked up on that at the time. But that’s the occasion in which I almost met Marcel Duchamp on the occasion of his almost complete works.” (laughs)

That’s a good story nonetheless.

“A good title for a story, yes.” (laughs)

I’d like to go back to the beginning, to your upbringing. Did you grow up in an artistic household?

“No, not at all.”

Was your family supportive of your film studies?

“I was meant to go study science. It caused a big argument in the family when I went and became an artist, but that got resolved in the end. I don’t think I ever visited an exhibition with my parents. I can’t remember them ever going to an art gallery. I found out about art through books in the library.”

And you cut them up?

(laughs) “No, I didn’t. The first person that first switched me onto art, and I hadn’t seen a real painting by him yet, was Van Gogh. Because I loved him so much, my mother bought me a collection of his letters to Theo for one of my birthdays, which is the only gesture supportive of art that I can remember in my family. I was completely hooked. I decided that I had to be an artist, a painter. So I started painting furiously and then got into art school the conventional way.”

You mentioned during the lecture that your mother saw your piece ‘Father Sky’ and recognised your father in the silhouette. So eventually she did find an interest in your work?

“Oh, yes. She tried really hard. For years and years she said: ‘I don’t understand what you’re doing, John.’ So I replied: ‘Don’t worry, mother. Nobody else does either.’ (laughs) ‘You’re not alone, I’m probably completely barking up the wrong tree’, I said. But that piece did touch her because she saw my father in the silhouette. So obviously I gave it to her. It still hangs on her wall, she’s just about to turn 97.”

‘Shadow 11’ (2014) – screenprint similar to ‘Father Sky’

That’s amazing. I also wanted to talk to you about the fact that your career had a ‘second spring’, as Frieze.com calls it, later in your life. How did that make you feel at the time?

“I was very excited when everyone finally caught up, I thought it was a dream, it was unbelievable. When I got all these wonderful reviews for my traveling show it was very, very exciting. I felt vindicated.”

Did it bother you that people weren’t paying attention before?

“Yes, I suppose it did. I became quite resigned. Early on, I began to realise people didn’t get what I was doing. I kept showing people my work and I couldn’t understand why they didn’t see what I was doing. I spent a lot of time trying to convince people to look at my work but I realised it was no good. The more I tried to get people to look at my art, the less prepared they were to even consider coming over to my studio or visiting me. I realised that was making me unhappy and stopping me from working as well. So I decided to put my energy into my art and into teaching. To allow the teaching to support my art. I thought: ‘I’ve built up a huge body of work. One day, somebody surely will look at it.’ But I didn’t really expect it to happen in my own lifetime. I’d given up on that, completely.”

So what did that experience teach you about yourself, why did you push on?

“Why did I carry on? I don’t know. Madness, I suppose. I’ve always been driven by the work, that has always been the main priority in life. Even when I was teaching I would dash back home to work. It was my great love. I enjoyed teaching but it was really a means to an end. My art was an escape from work and the rest of existence. A release.”

Would you use that as an example for other artists who feel like they’re not getting the recognition they deserve?

“Just cut off and escape into your art. Mind you, I do think it was foolish of me because after a while I think people could’ve understood my work. I could’ve done with a bit of gallery support a little earlier in life. I shouldn’t have had to wait until my fifties, I think. But it’s the way it went, and I’m quite happy with that.”

The stills that you usually work with in your collages are not of well-known actors, is there a reason you’re more drawn to the ‘failed’ actors and not the more famous ones?

“I tend to collect the stills that are not of value, so they’re anonymous. But the anonymous ones are the most valuable to me, because there is no association. They’re just people. There was a funny occasion at my 2011 Whitechapel show where there was a poster campaign of one of my images, using a woman who was completely unknown. It turned out that her grandchildren recognised her from the posters and told her about it. I didn’t get to meet her but she told the curator that she’d never made a film. Her images were circulating to try and get her work but she was told at the time that her nose was too big. She was completely confused as to how her image was suddenly circulating all the way around London.”

That’s incredible. I was also looking at your piece ‘Double Shadow LXIII’ and it really took me a minute to figure out how it worked. I was wondering if those kinds of mind tricks and the cognitive dissonance that takes place in viewers’ minds is something that you intend or enjoy?

“I like to suspend that moment of legibility in an image. Because that’s the moment when the image is just an image and no longer a transparent conduit to something else. And the longer I can suspend that, the better. With the Double Shadow pieces it becomes very complex and it takes a while to work out what’s going on. It’s a subtle threshold because you’ve eventually got to see what’s happening. That balance is very difficult to calculate. Duchamp used the words ‘arrest’, ‘snapshot’, in relation to found images. Stopping time, somehow. That’s what I’m trying to do; I’m trying to delay that point of recognition. In that little moment of delay, you inhabit the world of images. And that’s when you make contact with the imagination. Looking back at surrealism, a lot of them seemed to be doing very similar things.”

‘Double Shadow LXIII’ (2015)

You also mentioned in your lecture that you hide your failed collages until you can recycle them. How do you determine failure in your work?

“That’s the one thing that’s always totally unambiguous. I don’t know how, but I just know. I store those failures for future redemption, so to speak. If I’m in a bad mood, everything gets destroyed. I work a lot at night. As I get older it’s a lot more difficult to work all night but I still prefer the evening and the beginnings of night-time to work. So when I abandon a piece, it’s in the morning that I make those judgments as to what’s failed and what’s successful. There can be weeks that go by in which everything is a failure. At times I destroy everything and just go for a walk or do something else. There can be really bad periods like that, that go on month after month. Which is why I do other things like make films or silkscreen prints or write or give lectures. But when I’m working, nothing else diverts me.”

In a previous interview you mentioned ‘Un Chien Andalou’ by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí having quite an impact on you, especially the eye-cutting scene. Are there any other films or cinematographers that have impacted you?

“’The Third Man’ by Orson Welles is one of my favourites, as well as Warhol’s ‘Empire’. I thought Warhol’s films in general, like ‘Kiss’ or ‘Sleep’, were amazing and they had the biggest impact on my own film production. Oh, and Dziga Vertov was the most important filmmaker for my collage work. Chris Marker and his film ‘La Jetée’ were also really important to me.”

‘Empire’ by Andy Warhol (1964)

You’ve spoken about the influence of Max Ernst, de Chirico, Baudelaire, Joseph Cornell. Are there any artists working today that you find interesting?

“Yes. Christian Marclay, the man who made the 24-hour film, ‘The Clock’. What he did was take all these clips from films of clocks and put them into chronological order. So for 24 hours, all you’re looking at are different moments from famous films where watches and clocks appear. It goes minute by minute, all the way around. I like a lot of his work.”

Have you been in contact with him?

“Only remotely, we keep missing one another. But there are so many other artists I admire, most of them rather obscure. One of my favourite young artists is Becky Beasley. She was a former student of mine at RCA.”

Are you already working on new pieces?

“I’ve got three films that I’m still trying to complete but I’ve had to abandon working on those because I’m also making a book. Following my book ‘Crossing Over’, there will be a new one consisting of little image fragments. I’m also working on some new editions and prints. I’ve been preoccupied for the last six months by moving studios. That doesn’t sound like very much, but with the amount of work I’ve done over the years it’s a gigantic enterprise. I’ve bought a large house down on the south coast of England in which I can begin to bring out all of my work. It’s the first time that people will be able to see the work that I’ve made from the 1970s up until the 90s. Most people are predominantly familiar with my most recent pieces. Finally there will be a way of looking at the entirety of my work.”

All art by John Stezaker for ‘John Stezaker in Dialogue with Marcel Broodthaers’ (2016) unless specified

All art by John Stezaker for ‘John Stezaker in Dialogue with Marcel Broodthaers’ (2016) unless specified

“JOHN STEZAKER IN DIALOGUE WITH MARCEL BROODTHAERS”

13/10/2016 – 26/11/2016

Gallery Sofie Van de Velde

Lange Leemstraat 262

2018 Antwerp

Open every Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 2 PM until 6 PM

And every day on appointment: + 32 486 791 993