In a longform profile of Judith Joy Ross for Aperture in late 2021, the writer Rebecca Bengal meanders through the American photographer’s story, unfolding the idiosyncratic magic of her decades-long vision. “She is guided by a rapt, intense, wholehearted belief in the individual,” she writes, and then, “Ross is a master of the formal portrait, exquisitely executed with astonishing emotional clarity.” Later, she quotes the former MoMA curator Susan Kismaric too, who said of Ross, “Judith never projects, she never condescends or judges, but she intuits.”

I took these words with me when I started to spend time with Judith Joy Ross: Photographs 1978-2015, a new retrospective publication of Ross’ work, released earlier this year. Leafing through the pages—containing portrait after portrait after portrait—what first strikes a chord is the emotional lucidity Bengal refers to, how Ross cuts through to reveal something of the inner life of every person that stands in front of her camera, and how every person she photographs becomes equal before her—equal while remaining entirely individual.

The book starts out with a section aptly titled Beginnings, which takes the form of a tiny cluster of just six pictures including street scenes, a close-up portrait, and an image of two figures posing on the shore of New Jersey. Taken between 1978 and 1981, there is no immediate or obvious thread uniting these pictures, but nevertheless something intangible seems to hold them together—a sensitivity and a softness that shows us these pictures are from the same hand. Straight after, the book moves on to a section called Eurana Park encompassing Ross’ first major project and some of her most well-known pictures.

In 1982, Ross was treading water through a wave of devastation at her father’s death. His absence was swelling around her, she was lonely, and so she set out into the world with her camera, seeking connection, however fleeting. She took these pictures at a public swimming park, close to her faily’s old summer cabin in Weatherly, Pennsylvania. Her subjects here are all kids—teenagers mainly, and all of them have a sense of awkwardness and innocence that one imagines Ross might have found to be a salve in those early days of grief, away from the heaviness of adult life.

There’s a precious stillness to each of the portraits in this set—capturing something of the long slow summers we only know as children. Smiles are present but subtle, and water glistens on young faces. It’s soul-stirring to see these pictures so early on in the edit because they set the tone for the book to come, helping us to see how Ross developed as a photographer, ever-seeking new subjects, while always investing the same emotive weight as she had done in the park with those kids that summer.

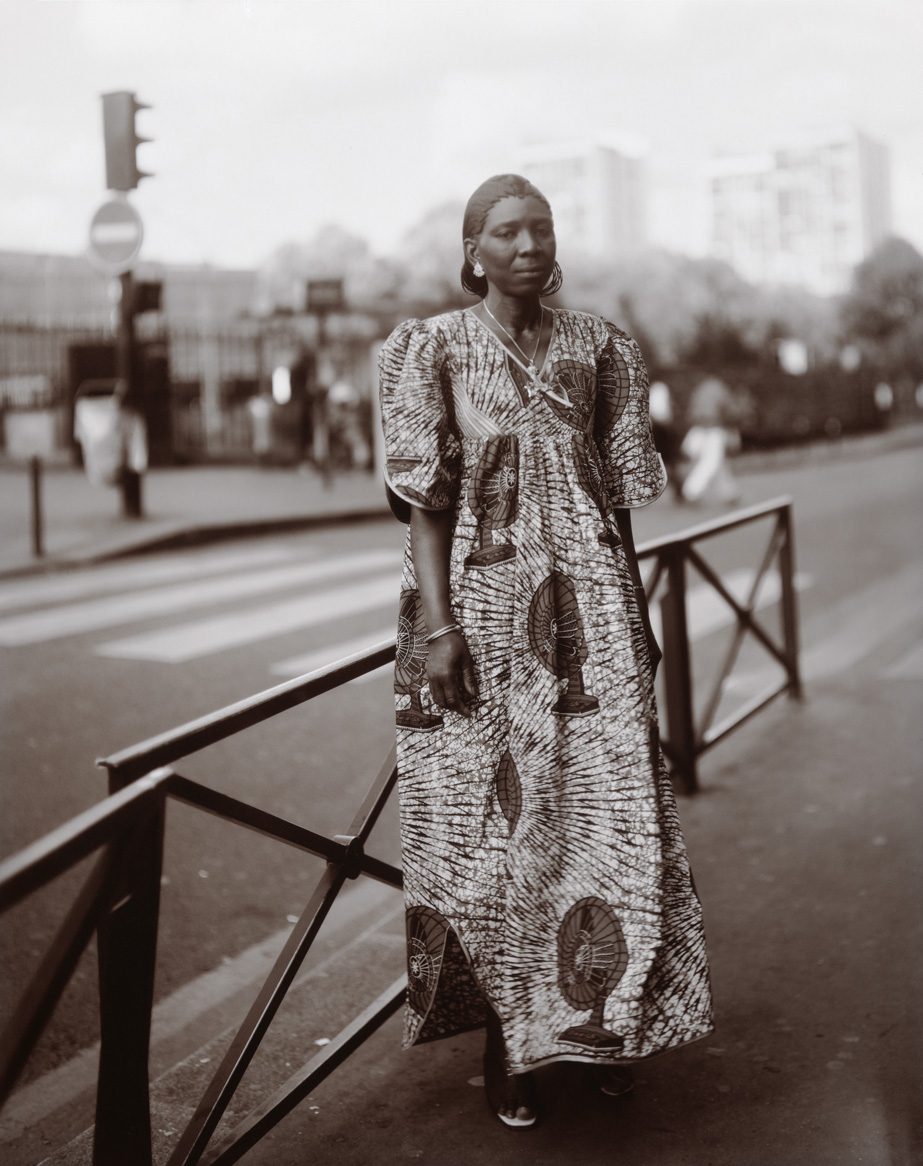

The book moves through many clusters of photographs, loosely organizing moments in Ross’ life together and giving some particular importance. It’s chronological for the most part, though occasionally a section jumps around between years. As the book wears on we see schoolboys and swimmers, gravediggers and grandmothers, firemen and families, brides and babies, and occasionally, a thematic selection emerges from the mass of dates and faces. Sometimes groupings are made simply under a particular place name, echoing the Eurana Park work—there’s Easton Park for instance, Eagle Rock Reservation, and Northeast Philadelphia. It’s all portraits though —showing how all of these places are their people.

Elsewhere, Ross makes groupings based on social categories or jobs—public school kids, for example, and army veterans. In one particularly affecting section, a series of images called Eyes Wide Open collects portraits of protestors. Holding plaques, they look out, gaze skywards, or with intensity into the camera. Much earlier on, Ross shares portraits of members of the United States Congress, taken in the same way as she photographs the protestors, with the same cool eye. Out in the street or up in the offices; the politicians and the people, everyone given the same framed space.

At some point, as the edit makes its arc towards the end of book, Ross has chosen to include a set of pictures a little different to the rest. Entitled Home – Rockport it details the quiet corners of the photographer’s home, like the street seen through gauzy net curtains and the garden blooming beyond the open back door. These are completely unpeopled pictures; a puncturing silence in a book otherwise full of faces. That way of disarming us through images also carries on in the final pages, where a few color pictures begin to appear in the edit—just three in fact, taken from 2011 onwards. How interesting it is to see this; a lifetime in black and white but here are the glimmers of a vision changing, leaving us to wonder where Ross is headed next.

In the colophon of the publication, there is a note on the printing of the images. Ross prints the majority of her work on gelatin silver chloride printing-out paper—a traditional, delicate and time-intensive process. Going on to describe the full process, the note points out how many variables there are throughout it. “Thus, each finished print, even those within the same edition, is one of a kind, a subjective product of an often unpredictable set of circumstances.” Just like the people she is photographing, each photograph itself is completely unique. That invites us to look back on the work differently, and to note the tonal shifts as they ebb and flow through the sequence.

What Ross has, people who have worked with her often say, is an intangible gift that means she can see something in people and pull at those threads to reveal a deeper essence when photographing them. Every picture she takes is the result of a meaningful encounter between photographer and sitter, whether that encounter lasted five minutes or five hours. In her profile of Ross, Bengal writes of a story she’d heard at some point. Apparently, the photographer An-My Lê once recalled how she’d played a game on the NYC subway with Ross, where she’d try to guess who Ross would pick to photograph. She was always wrong, she said, and that anecdote really encapsulates Ross’ vision, doesn’t it?

She sees something the rest of us don’t—until it’s a picture, of course. Once printed, her portrait always makes sense, and we see with clarity how arresting a person’s presence is. But Ross is able to see it before she clicks the shutter, to recognize something in a face and crystallize it, creating images of people full of humanity and quiet power. Weaving through several decades of the artist’s work, a rich constellation of those images are collected in this book.