A Broken Pair of Scissors: John Stezaker’s Pursuit of the Image

Collage artist John Stezaker broke his auction record at this month’s Frieze Week sales. In the year of his 70th birthday, MutualArt takes a look at his market presence, and his pursuit of “the image”

Adam Heardman / MutualArt

Oct 11, 2019

Collage artist John Stezaker broke his auction record at this month’s Frieze Week sales. In the year of his 70th birthday, MutualArt takes a look at his market presence, and his pursuit of “the image”

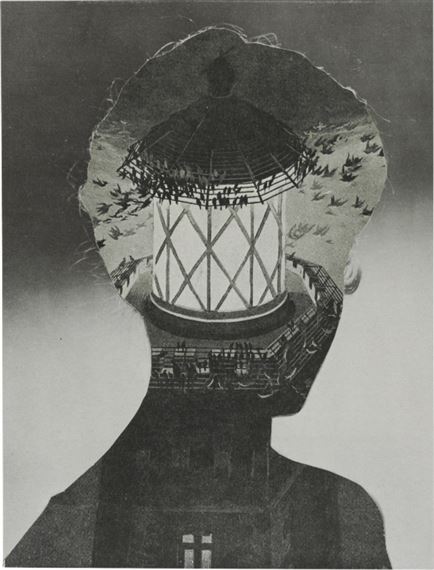

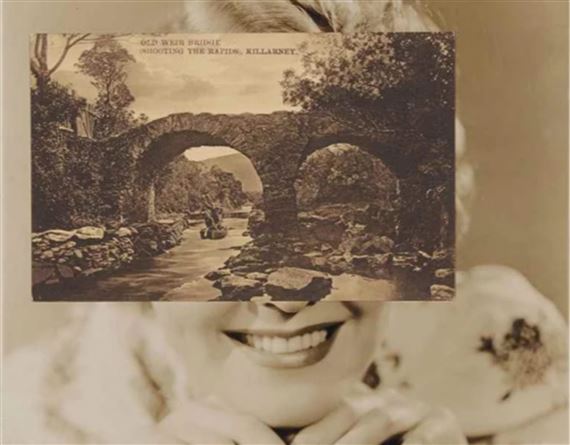

John Stezaker, Mask XXIX (2011)

“A broken pair of scissors is a more material object than a useful pair of scissors,” said John Stezaker in a 2010 interview with Andrew Warstat for parallax magazine. He’s engaging, here, in a deeply complex and academic discussion of the subject-object relationship, and how the nature of the viewed object in relation to the viewing subject is defined by the objects ‘usefulness.’ The conversation had its roots in the philosophy of Heidegger, and developed through Breton and Blanchot. The idea’s first definitive expression in visual art arguably came with Duchamp’s readymades.

John Stezaker, Kiss I (1979-82)

From Heidegger’s broken hammer to Stezaker’s broken scissors, we can draw a throughline of thought regarding ‘the image.’ Stezaker has arrived at the idea that a useless object is more ‘material’ because our relation to it is not defined by its use. A person’s relationship to a hammer is fundamentally altered if the hammer is broken. A broken pair of scissors is more like an image of a pair of scissors. A urinal turned on its side, called a ‘fountain,’ and placed in an art gallery is neither urinal nor fountain, and provides a crisis point by which ‘image’ and ‘theory’ fly apart into discrete categories.

John Stezaker, Film Portrait - Incision XII (2005)

As will be already clear, Stezaker is a very well-read guy. The simplicity of his cut-ups both masks and reveals a theoretical complexity, a deep well of thought and experience, borne out in his process that he himself has referred to as “another kind of image pursuit.” To create his collages, which have historically included text, portraiture, and landscape, Stezaker plunges into photographic archives, collecting and selecting images from criteria defined by his theoretical approach and, of course, by the intuitive feel of an artist. His practice is divided into collecting and assembling. In the Warstat interview, he reveals that he often spends the morning collecting images in one room, and the rest of the day assembling his own collages in another.

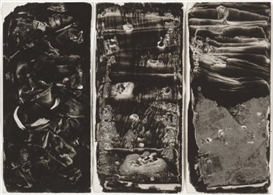

John Stezaker, Untitled (1989-90)

Fittingly for someone who pierces and fragments the images of the past, Stezaker places great emphasis on ‘damage’ and ‘destruction’ as processes by which a true and whole image reveals itself. “Pictures seem to bear the accidental scars of damage with a dignified indifference,” he says. Further, “damage also seems to reveal the opposite; the inviolability of the image; that the image is in some sense untouched by physical damage. The image is also elsewhere, and damage, it seems, is needed to create this awareness of the image as separation.”

John Stezaker, The Bridge XVIII (from the Castle Series) (2008)

In many of Stezaker’s works, the facial features of a portrait photograph are removed, and replaced with a natural landscape whose features suggest the absent face. In his own terms, Stezaker does damage to each image and thereby contributes to its inviolable truth. We see each image more powerfully, because we are compelled towards its damaged state. It’s something like the impulse of care or preservation which we feel towards our own bodies and extend to our kin.

John Stezaker, Untitled (2012)

But also, in splicing the two images together, Stezaker creates a third thing. And this third thing is a total image in itself. The work of art. The humor or the repulsion or simply the “I see what he did there!” appreciation that we feel as a result of the work’s ingenuity exists on its own, and can only exist in the destruction and re-appropriation of the original materials. That’s Stezaker’s genius: to preserve, and create, as he destroys.

On October 1st this year, a John Stezaker work sold for more than double its estimate, and nearly three times his previous record at auction. Kiss I (1979-82) went for $35,334 against a high estimate of $14,748 in the sale of the Jeremy Lancaster collection at Christie’s London, as part of their Frieze Week auctions. His previous most valuable work in the secondary market was sold back in 2015, Mask CXXIX (2011) raising $12,061 against an upper estimate bracket of just over $6,000.

John Stezaker, He (Film Portrait Collage) XXIV (2012)

Stezaker’s works crop up in esteemed private collections every now and then - as well as Lancaster, he has been collected by the likes of Mario Testino - and the strong performance of Kiss I (and the beginnings of an increase in consignor confidence, borne out in the boost in estimates) might tempt owners to sell. Stezaker’s market is one worth watching.

But, more importantly, he’s a contemporary practitioner whose incisive forays into the very nature of The Image are among our most valuable pieces of conceptual art. He has deep faith, and has contributed to a general faith, in the immortality of pictures, and their sublime potential. “Do images die?” Andrew Warstat asked Stezaker at the end of the 2010 interview. His answer bears remembering: “Yes, but with images this is not the last word. They can come alive again.”

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Articles Page