Articles in Ambulatory

'Gaps, glitches and speed bumps' by William Mackrell / September 17, 2015

William Mackrell, Gaps, glitches and speed bumps, Thursday 10 September - Sunday 13 September 2015, photo by AK Purkiss

"we understand space as the sphere of the possibility of the existence of multiplicity in the sense of contemporaneous plurality; as the sphere in which distinct trajectories coexist; as the sphere therefore of coexisting heterogeneity." - Doreen Massey

Performance is often described in terms of the body, spectatorship, duration, the spoken word, narrative. In art institutions it is included among what has come to be known as time-based practices or live arts. Amelia Jones, for instance, notes that performance has been “privileged precisely through its ephemerality and immediacy”. The current anxiety about the documentation and reenactment of performance confirms the perception that performance is impermanent in a strong sense. Everybody knows that performances occur in spaces but typically the performance is seen as something separate that is brought to the space and disappears from the space once it is over. In this way, performance has been theorized as primarily temporal rather than primarily spatial.

William Mackrell’s work combines sculpture with performance (including print and photography too) in a way that not only adds a temporal dimension to the sculptural sphere of objects, but adds a spatial element to it, as well. Not the kind of spatiality that animates installation art (a sort of extrapolation of the ‘spaces’ within paintings and sculptures) nor the bounded concept of space that attaches site-specific art to physical spaces. Mackrell’s work traverses the spatial dynamics of geography. I am not thinking of the traditional conception of geography as the study of territory or the poststructural misconception of space as the “domestication of time”, to use Ernesto Laclau’s words. Mackrell’s works respond to place and space through an embodied reflection.

Deux Chevaux (2011-2015) consists of a Citroën 2CV harnessed to two horses and driven, or ridden, through various specific places. Given its original purpose to supply motorized transport to farmers still using horses and carts in 1930s France, Mackrell’s montaging of these two modes of transport into one functional vehicle is an historical conundrum. If conceptually it is a temporal folding of history upon itself, it has a strong geographical significance in its realization. A great deal of Marckrell’s time was taken up in negotiating with the local authorities to obtain written permission to take the horse drawn car along specific routes at specific times.

His walking piece, Going to the Gallery (2013), is a spatial study. Writing the words ‘going to the gallery’ on a roll of paper as he makes his way on foot from the studio to the gallery, Mackrell links two places not only through his action but through his mantra. While still outside the studio he writes ‘going to the gallery’, as if the two spaces were already, through his intention, bridged and bonded. As well as the movement of the artist from one place to another, a roll of paper, now absent from the studio is left in the gallery. This work thus transposes the experience of space into what might have once been called a piece of text art, which appears in the gallery as a little heap, not unlike Robert Morris’ iconic piles of felt, of displaced material.

At least since the early eighteenth century a man who walked from his studio to a gallery would be a bearer of spatial displacement. Daniel Defoe celebrated this in his panegyric to trade: “The cloth for the man’s coat comes from Yorkshire;… the waistcoat … from Norwich. The breeches are … from Devizes, Wilts … His yarn stockings are from Westmorland. His hat is a felt from Leicester. His leather gloves come from Somerset, his shoes from Northampton”. Today, David Harvey asks where your breakfast comes from (sugar, coffee, milk, cups, etc), saying that these products link you with millions of workers around the globe. He calls these ‘spatial linkages’. Mackrell’s works create spatial linkages that make visible the invisible threads that connect places together.

Gaps, glitches and speed bumps commissioned by RBS for the Ambulatory category of Sculpture Shock 2015 makes its way, eventually, to the gallery but it takes place largely on public transport. Sat upstairs on the bus, Mackrell draws lines that are scattered by the swaying, stopping and swerving that jolts all the passengers. He draws on a print of sheet music in which the rows of lines have been bent into a circle. At the same time, four singers chart the journey with improvised sounds, stopping abruptly whenever the bus reaches a stop or a red light. Fellow travellers turn to listen and look, pointing and whispering, giggling and smiling.

“The real import of spatiality”, critical geographer Doreen Massey says, is “the possibility of multiple narratives”, or what she calls “coevalness”. Gaps, glitches and speed bumps is Mackrell’s most coeval work to date. The bus has a fixed route and is timetabled according to a semi-rigorous schedule, but the people who jump on and jump off have their own destinations and their own narratives. Buses are public not in the Habermasian sense of places where opinions are exchanged and public opinion is formed collectively, but in the sense of a zone in which people come together temporarily and share space, like a park, a zoo or a shopping mall. Like the scenes portrayed by Manet, then, the bus is a conspicuous reminder of the city as a place of coeval existence. Mackrell’s intervention in the bus, by adding just one or two new narratives to the scene, highlights the fact that there were multiple narratives here all along.

Mackrell did not hire a private bus to realize his drawings and improvised singing. It would have been reasonable to do so but if he had then the work would have remained spatial but would have been far less coeval. The route that the private bus took would have been determined solely by the artist and the fellow passengers would have been there to witness the work. By joining a public bus on its regular journey, carrying passengers to their individual destinations, Mackrell’s work inserts itself into the space that others occupy for their own purposes, mid-stream so to speak. The work belongs in the same space, in the same intersection of journeys and narratives, that any passenger would encounter walking down a busy street, catching a train or stepping onto the bus.

Taxi drivers famously enjoy the full benefits of coevalness but taxi passengers do not. If we do not typically experience the coevalness of bus journeys in full, this is because our journeys are shaped by the polite avoidance of fellow passengers. In fact, coevalness is generally not something that we experience directly. It is a background feature that structures contemporary life. Like the spatial linkages that pins your breakfast to the world without you necessarily having any idea about what these linkages actually are, coevalness is structural not phenomenological. Mackrell makes coevalness phenomenological by assigning the movement and noise of passengers to the score of the work.

James Clifford roots the practice of traveling in the Greek term theoria: “Theory is a practice of travel and observation, ... a product of displacement. To theorize, one leaves home.” Aesthetics is the result of a similar process, applied to objects and subjects alike. The modern institutions of art - including the public museum, the emergence of an art public and the publishing of art criticism - were unprecedented but can be understood best as based on the modern experience of Greek and Roman artefacts displaced from their original contexts. Art and aesthetics are born when crafted objects left home, or, more precisely, were seized by foreigners. Art is in a perpetual state of leaving home. What Gaps, glitches and speed bumps demonstrates is that the displacement of the aesthetic from the museum does not return it to a pre-aesthetic function or utility, but percolates the aesthetic through small pockets of the everyday.

Written by David Beech

Essays, Ambulatory April 29, 2019

Notes from the Studio - William Mackrell / July 27, 2015

William Mackrell in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

Why are certain subjects harder to describe in words than others?

Why is it that it has taken me weeks to try to find the right words to describe William Mackrell’s art practice for the Sculpture Shock Abulatory award.

A white sheet full of expectations.

While it’s fresh and clear in my brain-the words just make me stumble.

So here I am stumbling, struggling with too much effort, trying to grasp the right: Language.

Language can hinder us, make us be misunderstood, embarrassed.

Despite its constructive beauty, the written or spoken language can appear superficial and false. The bridge between thoughts and words is a conscious mental practise that shuns honest expressions.

I often think that the core of our intentional message remains in some sort of obscurity behind the spoken and written word.

William Mackrell in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

"drawing is the more primitive important language to the human race than the written word and should be taught to every child in the same way as the written word..." John Ruskin

William often uses drawing in his work. Its his text, his language.

It is honest clear and exciting. Its often used as an imprint of a certain recorded time.

William is not just using the hand and the pen as drawing tools, he uses his whole body.

William recently performed 'tongue drawings' to express his thoughts in the studio.

He lets the experience, the act he performs, resonate through his body and leave marks on the paper. This is his text, his language.

And even if he would occasionally use words, the words themselves becomes a drawn line of action in space.

As the audience, we can all feel the messages William conveys by looking at him. And we will understand the marks. There is no embarrassment or misunderstanding. William's drawings unfold a depth in ourselves - a common collective comprehension of our human bodies, senses, and functions.

William Mackrell in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

As much as I try and would like to explain the complex thoughts that come up in my mind in words after visiting William, I believe we have to experience the performance ourselves to read its full meaning.

William's Ambulatory piece of work for Sculpture shock will take place in a bus. He will draw the experience of an every day bus journey, his body movements following the movements of the bus, creating a drawing with pen on paper.

Along with him, singers will with their own vocal medium draw their own lines in space.

So lets take a seat, and enjoy an everyday journey on a bus with William who will bring us to the higher levels of our human capacities.

William Mackrell in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

Two pieces of advice before the trip:

1. Don’t buckle up. There are no seat or security belts to fasten in the bus (Williams work will never be secured!)

2. And do NOT leave any personal belongings on the bus. (Let us not leave the bus and forget our experiences. Let us remember, learn from them as a new personal belonging that is ready to use and be explored)

Written by Nina Wisnia

Notes from the Studio, Ambulatory April 29, 2019

William Mackrell in Context - Deciphering Duration / July 16, 2015

Art can explore the concept of time and humanities’ relationship with time in a variety of ways, artists having often chosen to engage with ideas of time through the nature of the medium itself.

As performance art happens in real time a connection with the audience or participants is made as they are fully immersed in the experience of the piece. The fact that, in pieces such as Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, the art existed in a temporal rather than physical sense served to elevate the experience as it itself became the art, as opposed to a physical product produced by the artist. Kaprow developed his performance art as a medium explicitly engaged with time, describing his intentions to move away from ‘making pictures as figurative metaphors for extensions in time and space’, making the relationship between art and time more direct.

In Tehching Hsieh’s piece ‘One Year Performance 1980-1981’, also known as ‘Time Clock Piece’, a literal relationship was made between art and time, as the piece entailed the artist punching a time clock every hour, all day and night for a year. Hsieh’s passing of time with such a repetitive action without tangible product meant that the meaning of time was lost to a certain extent. The piece invited consideration of the meaning of ‘wasting time’, as an action associated with productivity, punching a time clock, prevented outside productivity in the artist, through its strict demands.

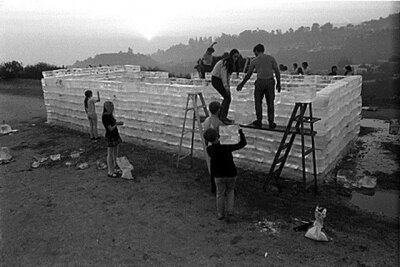

Allan Kaprow, Fluids, photographed by Dennis Hopper in Beverly Hills, October 1963

‘One Year Performance 1980-1981’ was one of six durational art pieces performed by Hseih, five of which took place over a year. The choice of a year was explained by the artist in Mousse Magazine, as he stated that ‘One year is the basic unit of how we count time….It is about being human, how we explain time, how we measure our existence.’ This sheds light on both the piece’s consideration of human quantification of time, and how it has made a physical marker of the division of time.

Time based art is often created in mediums other than performance art, however, as it regularly takes the form of media art. Video art often involves the idea of time, as the nature of the medium allows techniques such as looping to be used, allowing pieces to be potentially infinite, possibly to provoke a reduction in the perceived importance of time on the viewer.

Fischli and Weiss’ piece for the 1995 Venice Biennale, for example, invited a consideration of time and its value as they presented 96 hours of footage of car journeys that had taken place in Zurich. In describing their intentions in the work Fischli said that the piece allowed the viewer to place value on different aspects of the work, by choosing a particular monitor and moment to pay attention to, and deciding how long to remain looking. The artist stated in an interview with Frieze Magazine that “They have to ask themselves the same question as we do: what shall I waste my time on? And by giving them this time I enhance the value of these things”.

William Mackrell’s piece ‘Going to the gallery’ (2013) engaged with time as it made a physical representation of time and the artist’s experience travelling from his studio to the gallery, as he continuously wrote ‘going to the gallery’ on a roll of paper, the used material accumulating and bearing a physical marker of the journey as it became dirty or torn. This piece thus translated time and experience into a physical medium, displaying another way to develop the relationship between art and time. For his forthcoming Sculpture Shock AMBULATORY intervension Mackrell will continue this theme as he plans to reflect the live journy of a Routmaster bus through automated drawing and sound. In this way the physical journy, and therfore time, will once again be reflected in different forms, as well as becoming a shared exsperience for the passengers.

Written by Octavia Young

Essays, Ambulatory April 29, 2019

'Making Progress' by Alexander Costello / September 1, 2014

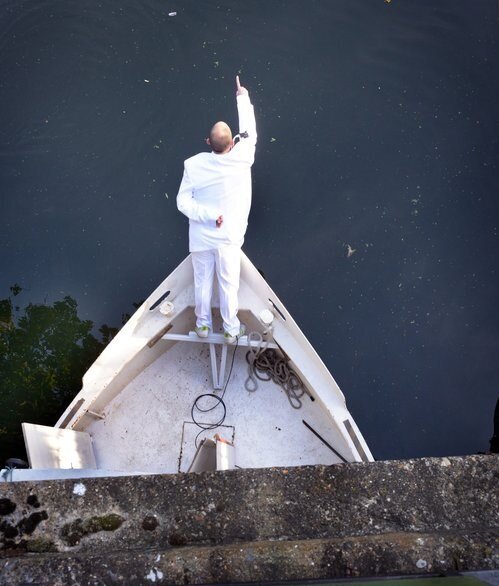

Alexander Costello, Making Progress, performance, 2014, photo by AK Purkiss

A white barge was to be seen floating slowly along the Regent’s Canal; nothing unusual in that. If you looked closely, though, you could see a figure standing motionless in the prow pointing ahead as though urging the vessel to maintain its forward momentum.

This was neither a carved wooden figurehead nor the skipper navigating shallow waters, but the artist Alexander Costello performing ‘Making Progress’, a four day journey aboard a barge that doubles as the Fordham Gallery.

For the occasion, he wore a white suit that blended in with the fabric of the boat, so that he could easily be mistaken for a fixture. Copious sleeves hid the steel structure made by the artist to support his arm during the journey; this made his ability to sustain such an awkward and absurd pose over many hours seem little short of miraculous.

‘I’ve never not performed’, Costello tells me. ‘As a boy I was a chorister standing still for hours on end and, later, I became the front man for a band. It’s nice to be live; I like the endurance aspect of being in the moment – feeling the doing, experiencing things in the now. Whatever happens, happens. I like testing myself and asking “How am I accountable?”

Alexander Costello, Making Progress, performance, 2014, photo by AK Purkiss

Attached to his pointing arm, a video camera provided live footage to a screen below deck so that passengers could share Costello’s privileged view of the canal and its banks as the boat glided inexorably forwards into the future. They could also watch people on the towpath responding with surprise, hilarity or dismay as they caught sight of the artist pursuing his apparently pointless task with such determination and focus.

‘That’s exactly what it was’, agrees Costello: ‘a poor sod persisting in nothingness. The whole point of the performance was this steady nothing – in all its metaphorical glory!’ This remark brings to mind Samuel Beckett’s play ‘Waiting For Godot’, in which two benighted fools, Vladimir and Estragon, persist in waiting for the arrival of someone called Godot even when their vigil appears increasingly fruitless. The more time they commit to waiting, the more they feel the need to continue. ‘Beckett is massive’, affirms Costello. ‘Even when people are offered a fresh start, they still want and expect the things they are accustomed to.’

On the one hand, the journey was like any other; it passed the time pleasantly while ferrying passengers from A to B; and like many performances, Costello’s offering was light hearted, humorous and transitory. But while passing the time, like Beckett’s play, it had the potential to stir up the dark silt that lies beneath the beguiling surface of performance and encourage consideration of more serious issues.

Travelling along the canals of north London from Camden Lock to Tottenham Hale, the barge passed through Kings Cross, Haggerston, London Fields, Hackney Wick and the Olympic Park – areas transformed beyond recognition by the ambitious programme of regeneration embarked on in preparation for the London Olympics of 2012. In the process, the empty warehouses, derelict factories and small businesses that once lined the canal banks were refurbished or replaced by blocks of luxury flats that invite the well-heeled to elbow out poorer residents.

Some saw the development as a much-needed improvement; others viewed it with disgust as wanton vandalism. Costello deliberately chose the route and the title, ‘Making Progress’ to provoke questions about the concept of progress – what it means and it’s intended and unintended consequences. Does the notion of progress spur us on toward a desirable future or, in the vain pursuit of unattainable goals, does it encourage the destruction of things we should hold dear? Where are we heading individually and collectively, and what would constitute a worthy ambition, a meaningful journey or a useful life?

Alexander Costello, Making Progress, performance, 2014, photo by AK Purkiss

‘As a teacher I’m expected to subscribe to the notion of ‘making progress’’, explains Costello, who is a teacher as well as an artist. ‘In life we’re always on a journey – going forwards rather than retreating – but some people need more time to get started and, in the education system, late developers are written off.

“At university I made sure I achieved something every day, but things soon became strained. I didn’t want to force the work, so I taught myself to do nothing, to enjoy the nothing (the empty canvas) – to let things gestate and allow the work to happen. I’m interested in processes; if I know where I’m going – if the idea is already in my head – its no good to me. If I’m too much in control, whatever made it interesting in the first place no longer exists.’

Does he believe that art can change anything? “Yes”, comes the emphatic reply. ‘This project is ridiculously silly, but also very important vis-à-vis social politics. We’re encouraged to equate progress with making things bigger, better and faster, but this acceleration leads to homogenisation; which generates conservatism. And who orchestrates change? Big corporations.

‘Like the slipstream off the end of my finger, progress always remains just out of reach, so I’m encouraging people to question what “making progress” actually means, and the silliness is the doorway. At one time I tried to be funny but it didn’t work, partly because that wasn’t the point, partly because the desire to entertain encourages mediocrity. So now the audience has to take me as I come. I’m interested in ideas; I like hard work, something rich and nourishing, a real chew.’

Written by Sarah Kent

Ambulatory, Essays April 29, 2019

Notes from the studio - Alexander Costello / September 1, 2014

How important is the written or spoken word to the conception of your works?

AC: The faults, oddities, devices, misinterpretations and slippages that exist in language are the unconscious, subliminal foundations to ideas that find themselves re-presented in my more solid visual work.

Alexander Costello in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

Who are the artists you most admire and which have had the greatest impact on your thinking and your work?

AC: Big hitters for me are Manzoni, Baldessari, Tati, Prince, McLean, WC Fields, Bas Jan Ader, Salvatore Scarpitta, Laurie Anderson, Beckett, Abramovic, Yves Klein, Robert Rauschenberg, de Chirico, Pettibon, Bukowski, Herman Hesse, Kurt Vonnegut, Fontana…

Your Sculpture Shock residency is called ‘Making Progress’. What do you perceive as ‘progress’?

AC: I don’t actually know what progress is supposed to be, what it looks like or what we should be doing with it, but the idea of it dominates how we value and locate ourselves today. I suppose getting somewhere with something, wherever that is or whatever it looks like, and coming to terms with what happens was always going to happen. Not to be confused with making things better though. There is nothing better than being inside the moment of making, time spent pushing at things, teasing confidence with doubt, and just keeping going. Because of that, endings interest me and the anticipation of the next thing. There is always the next thing.

In the wider social (western) context, progress often skips hand in hand down the street with pro-activism the mighty slayer of inertia, and as such is perceived as something positive for society. I am uncomfortable with this perception, as much as I am also uncomfortable with progress being linked to the importance of accountability, when accountability concerns a race to the bottom. Steve Aylett said that “progress accelerates downhill.” I am happy to know that and keep it in mind. As such, progress concerns ideas to do with ‘moving forward’, be it as an individual or society, which is perhaps a flawed consensus. Who is progress for? is a very important question to ask.

Alexander Costello in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

You said that the film The Bed Sitting Room based on the play by Spike Milligan and John Antrobus provides the context for your residency. Can you elaborate on this?

AC: The world has been destroyed by a nuclear war which lasted only 2 ½ minutes and only a few survivors remain. The landscape is a desperate environment of cutlery, mud and rubbish. There is nothing to look forward to. Dudley Moore and Peter Cook appear as the police, floating over the heads of the survivors in a hot air balloon and insist that everyone keeps moving - moving forwards - as if that is what is required and is the necessary default position, in the given circumstances. The fact that it means absolutely nothing goes unquestioned. The world is a tabula rasa. Despite having the opportunity to start again, the survivors cling on to their perceived, ingrained and oppressive social norms and aim for and rely on the same mundane things like a Tesco, a bank, etc. when rebuilding their world. The absurdity is that having being given the world, they cling to their ideals and habits of progress.

Humour and the absurd are cornerstones of your work. What do you hope to achieve by using these ‘tools’ and how do they help convey your message?

AC: Humour is where the circle of seriousness and gravity comes to an end. Deadpan is at that fine point, and it is the means of entry and engagement with my work. All art is funny, and as such should always be taken seriously. Humour is a way of communicating something that is both funny and critical, an unwelcome observation or the uncovering of an embedded but dysfunctional social norm. Utterly ridiculous in delivery, utterly serious in content.

What impact do you hope your work to have on the viewer? What is the importance of public spectacle to you?

AC: I do not expect people to immediately understand what I am doing or what the point of the work is but I do hope to create strong images which lodge a future thought in their heads. Sometimes people need some thoughtful respite in order to progress.

Alexander Costello in the Sculpture Shock Studio, photo by AK Purkiss

How important is site specificity to your work? To what extent do you tailor your pieces to a particular ‘public landscape’ as you put it?

AC: The ‘public landscape’ is like a live canvas and back drop to my performance and video work. All my work is a response to people or places that punctuate the brusque contingencies of the everyday. I choose to respond, either by challenging these experiences or reflecting on them. I suppose there are 2 types of artistic process I engage with. The work you make as a process of making one thing after the other, where work itself generates ideas for new work and development. The other is making work in response to the site specific, whether it is a space, an incident, an object or environment. The site-specific is often a peopled space and experienced differently, person to person. As such, there is a greater chance to interact, interrupt, subvert and play with it through the types of interventions I design.

How do you feel about the impermanence of the performance components of your work in contrast to the more lasting nature of the text based, video, object making, drawing and painting elements? Are these intended as the documentary part of the piece, standalone works, or perhaps both?

AC: One of my firm beliefs is ‘It’s Not About The Thing. It’s About All Of It And Doing Things.’ Everything informs everything else. As such, my performance work does not need to be anything else it is not. As an impermanent medium I’m all right with it occupying the very moment it is supposed to, as that is the moment. In fact, it lends itself well to making sure that ‘What something is, is exactly what it is, and what it was always going to be.’